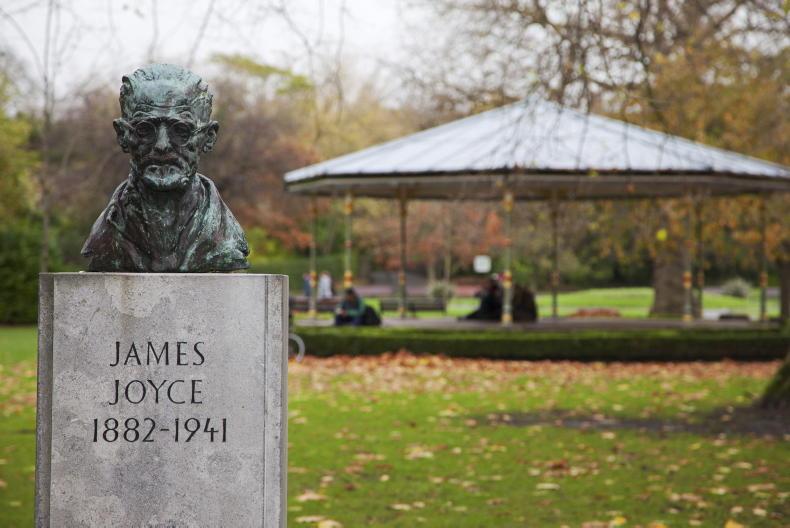

About Philip Joyce

My name is Philip Joyce and I am a grandson of Charles Joyce, youngest

brother of James Joyce of Ulysses notoriety.

I was born in Rathgar, Dublin in 1947 following a severely cold spring which lasted until nearly June. I only lived in that parish for a short time before being moved to the new housing developments in north-side Ballymun of the late ’40s.

I was the third eldest of 11 children. The first-born, Paul, only surviving a very short while and my older surviving brother, Bob, departing this world in 2018 at the age of 72.

We lost another brother, Derek, in tragic circumstances during the bitter December of 2010. The last-born, Patrick, survived for only a few days. I now have two remaining brothers, Tony in London and John in east Co Cork.

My four sisters, Marjorie, Carol, Mary and Dorothy reside in Dublin. (Carol got to name the Irish Naval ship, L É James Joyce, when it was commissioned in Dun Laoghaire nearly seven years ago.)

Our Mother was of a musical/showbiz family and Dad was an optician, initially working for Billy Morton of athletics fame and eventually running his own business from the time of Billy’s death.

Our house in Dean Swift Road, Ballymun came with a very large garden but Dad was not into horticulture and gave away much of the topsoil to a neighbour.

Despite the fact that we were living only a few miles from Dublin City centre, we were surrounded by farming land and many of Mother’s newly acquired friends were farmers.

There was little traffic on the roads of Dublin in the ’50s and I recall going for walks on Sunday and barely counting maybe ten vehicles in the space of a few hours!

Sometimes, on our way to school in Glasnevin, a parish nearer to the city centre, we would cross into a dairy farm. A neighbour of the Sacred Heart Primary School kept goats so we were well acquainted with many farm animals.

Later on, following a move to Clontarf and on my way to O’Connell’s Secondary School, I would encounter herds of cattle and flocks of sheep being driven along the Ballybough Road towards the Navan Road Mart or to be shipped from Dublin Port to the UK.

There was still a fair amount of horsedrawn goods vehicles in Dublin at the time and our door-to-door vegetable seller would often allow me to accompany him on his rounds sitting up on the dray. What a thrill it was to see his horse bounding free into its overnight field.

It is little wonder that my grand-uncle James was able to describe agri-nuances so well in Ulysses, his world-famous novel set in Dublin of 50 years prior to my humble escapades.

The gate at the Forty Foot free public outdoor ocean swimming area in Sandycove, County Dublin.

One of the earliest references is found in the first chapter, Telemachus, when a very welcome milk-lady comes to the Sandycove Martello tower wherein Stephen Dedalus is a brief guest of the tenant, Buck Mulligan and an English student, Haines. (James Joyce WAS a guest of Oliver St John Gogarty here for a brief spell in reality.)

“‘The milk, sir,’ she announced……….

…………Stephen reached back and took the milk jug from the locker.

‘How much, sir?’ asked the old woman.

‘A quart,’ Stephen said.

He watched her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers.

Old shrunken paps.

She poured again a measureful and a tilly. Old and secret she had entered from a morning world, maybe a messenger. She praised the goodness of the milk, pouring it out.

Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle. Silk of the kine and poor old woman, names given her in old times. A wandering crone, lowly form of an immortal serving her conqueror and her gay betrayer, their common cuckquean, a messenger from the secret morning. To serve or to upbraid, whether he could not tell, but scorned to beg her favour.

‘It is indeed, ma’am,’ Buck Mulligan said, pouring milk into their cups.

‘Taste it, sir,’ she said.

He drank at her bidding.

‘If we could only live on good food like that,’ he said to her somewhat loudly, ‘we wouldn’t have the country full of rotten teeth and rotten guts. Living in a bogswamp, eating cheap food and the streets paved with dust, horsedung and consumptives’ spits.’…………..

………Haines said to her, ‘Have you your bill? We had better pay her, Mulligan, hadn’t we?’………

…….‘Bill, sir?’ she said, halting. ‘Well, it’s seven mornings a pint at twopence is seven twos is a shilling and twopence over and these three mornings a quart at fourpence is three quarts is a shilling and one and two is two and two, sir.’……….

…….Stephen filled a third cup, a spoonful of tea colouring faintly the thick rich milk. Buck Mulligan brought up a florin (two shillings), twisted it round in his fingers and cried, ‘A miracle!’

He passed it along the table towards the old woman, saying, ‘Ask nothing more of me, sweet. All I can give you, I give.’

Stephen laid the coin in her uneager hand.

‘We’ll owe twopence,’ he said.

‘Time enough, sir,’ she said, taking the coin. ‘Time enough. Good morning, sir.’”

Calypso chapter

In the Calypso chapter of Part II, Mr Bloom’s desired meal of “thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hen-cod’s roe…….” and… “grilled mutton kidneys” have become world renowned menu items for any literary celebration of the novel and author.

A visit to Dlugacz’s pork butcher later in that chapter takes us back to a shopping scene of the times – with an added peek into Mr Bloom’s lecherous mind as he endeavours to follow a hip-swaying neighbour back to her home.

As he waits to complete his dealings with the butcher he is distracted by an advertisement on a meat-wrapping newspaper of a farm in Turkey. His mind wanders to the remote possibility of purchasing the farm for the purpose of growing trees!

On his return home, he observes the unproductive nature of his back garden – particularly its “scabby soil” which could be improved by “the hens in the next garden: their droppings are very good top-dressing. Best of all, though, are the cattle, especially when they are fed on those oil-cakes. Mulch of dung. Best thing to clean ladies’ kid gloves. Dirty cleans. Ashes too. Reclaim the whole place. Grow peas in that corner there. Lettuce. Always have fresh greens then.”

Draught-horses

Joyce observed the draught-horses used for dray and carriage work; as Mr Bloom approaches a cabman’s stand in the city.

“He came nearer and heard a crunching of gilded oats, the gently champing teeth. Their full buck eyes regarded him as he went by, amid the sweet oaten reek of horsepiss. Their El Dorado. Poor jugginses! Damn all they know or care about anything with their long noses stuck in nosebags. Too full for words. Still, they get their feed alright and their doss. Gelded too; a stump of black gutta-percha wagging limp between their haunches.. Might be happy all the same that way. Good poor brutes they look. Still, their ‘neigh’ can be very irritating.”

Hades chapter

A reference to the weather is made in the Hades chapter – “It’s as uncertain as a baby’s bottom,” (Mr Dedalus, Senior) said as he accompanies Mr Bloom to the Paddy Dignam burial in Glasnevin Cemetery.

As they traverse Dublin’s northside in the carriage, they encounter a mixture of cattle and sheep being herded through the streets for the boat to Liverpool.

“The carriage galloped round the corner. Stopped.

- What’s wrong now?

A divided drove of branded cattle passed the windows, lowing, slouching-by on padded hoofs, whisking their tails slowly on their clotted bony croups. Outside them and through them raddled sheep bleating their fear.

- Emigrants, Mr. Power said.

- Huuuh! The drover’s voice cried, his switch sounding on their flanks. Huuuh out of that!

Thursday, of course. Tomorrow is killing day. Springers. Cuffe sold them about twenty quid each. For Liverpool probably. Roast beef for old England. They buy up all the juicy ones. And then the fifth quarter is lost: all the raw stuff, hide, hair, horns. Comes to a big thing in a year. Dead meat trade. By-products of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine. Wonder if that dodge works now getting dicky meat off the train in Clonsilla.

The carriage moved on through the drove.

- I can’t make out why the Corporation doesn’t run a tramline from the park gate to the quays, Mr Bloom said. All those animals could be taken in trucks down to the boats.

- Instead of blocking up the thoroughfare, Martin Cunningham said. Quite right. They ought to.’”

Horse racing

An interesting horse-racing story wends its way through Ulysses; Mr Bloom, carrying a newspaper, is met by one Bantam Lyons, a follower of the “gee-gees”.

It is the day of the Ascot Gold Cup and Lyons requests a look at Bloom’s newspaper for the racing page. Mr Bloom offers it to him saying words to the effect that he was going to throw it away, anyway.

As it happens, a 20/1 outsider is running in the race called Throwaway and Lyons takes Bloom’s words as a tip. Throwaway wins on the day (and this can be checked on the internet for 16 June, 1904).

Mr Bloom has no interest in horse-racing, but word gets around that he has made a “packet” on the bet. When he fails to “stand” a drink to various acquaintances afterwards, he is deemed to be a bit of a “tight-wad” as the Americans would put it.

Food

These are some of the various farm/food connected references in this giant among novels.

From the nearby dairy farms of Ballymun, Dublin, of the ’50s I am now resident in my wife’s parish of Clonakilty, west Cork, where, if I look out through our back window, a dairy-farmland stretches for about 2km up to the loftily-positioned 100 hundred year established Darrara Agricultural College – and it is heaven!

Bloomsday takes place on 16 June.

Read more

From the Civil Service to crime thrillers

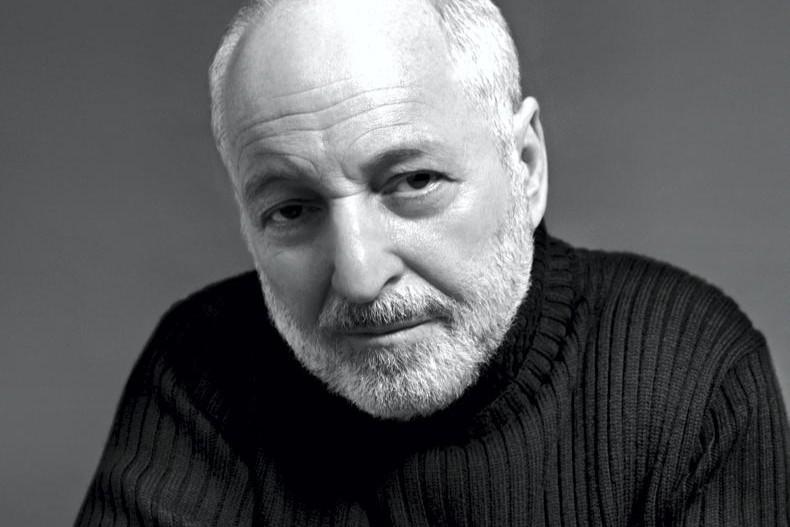

The man behind the words

About Philip Joyce

My name is Philip Joyce and I am a grandson of Charles Joyce, youngest

brother of James Joyce of Ulysses notoriety.

I was born in Rathgar, Dublin in 1947 following a severely cold spring which lasted until nearly June. I only lived in that parish for a short time before being moved to the new housing developments in north-side Ballymun of the late ’40s.

I was the third eldest of 11 children. The first-born, Paul, only surviving a very short while and my older surviving brother, Bob, departing this world in 2018 at the age of 72.

We lost another brother, Derek, in tragic circumstances during the bitter December of 2010. The last-born, Patrick, survived for only a few days. I now have two remaining brothers, Tony in London and John in east Co Cork.

My four sisters, Marjorie, Carol, Mary and Dorothy reside in Dublin. (Carol got to name the Irish Naval ship, L É James Joyce, when it was commissioned in Dun Laoghaire nearly seven years ago.)

Our Mother was of a musical/showbiz family and Dad was an optician, initially working for Billy Morton of athletics fame and eventually running his own business from the time of Billy’s death.

Our house in Dean Swift Road, Ballymun came with a very large garden but Dad was not into horticulture and gave away much of the topsoil to a neighbour.

Despite the fact that we were living only a few miles from Dublin City centre, we were surrounded by farming land and many of Mother’s newly acquired friends were farmers.

There was little traffic on the roads of Dublin in the ’50s and I recall going for walks on Sunday and barely counting maybe ten vehicles in the space of a few hours!

Sometimes, on our way to school in Glasnevin, a parish nearer to the city centre, we would cross into a dairy farm. A neighbour of the Sacred Heart Primary School kept goats so we were well acquainted with many farm animals.

Later on, following a move to Clontarf and on my way to O’Connell’s Secondary School, I would encounter herds of cattle and flocks of sheep being driven along the Ballybough Road towards the Navan Road Mart or to be shipped from Dublin Port to the UK.

There was still a fair amount of horsedrawn goods vehicles in Dublin at the time and our door-to-door vegetable seller would often allow me to accompany him on his rounds sitting up on the dray. What a thrill it was to see his horse bounding free into its overnight field.

It is little wonder that my grand-uncle James was able to describe agri-nuances so well in Ulysses, his world-famous novel set in Dublin of 50 years prior to my humble escapades.

The gate at the Forty Foot free public outdoor ocean swimming area in Sandycove, County Dublin.

One of the earliest references is found in the first chapter, Telemachus, when a very welcome milk-lady comes to the Sandycove Martello tower wherein Stephen Dedalus is a brief guest of the tenant, Buck Mulligan and an English student, Haines. (James Joyce WAS a guest of Oliver St John Gogarty here for a brief spell in reality.)

“‘The milk, sir,’ she announced……….

…………Stephen reached back and took the milk jug from the locker.

‘How much, sir?’ asked the old woman.

‘A quart,’ Stephen said.

He watched her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers.

Old shrunken paps.

She poured again a measureful and a tilly. Old and secret she had entered from a morning world, maybe a messenger. She praised the goodness of the milk, pouring it out.

Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle. Silk of the kine and poor old woman, names given her in old times. A wandering crone, lowly form of an immortal serving her conqueror and her gay betrayer, their common cuckquean, a messenger from the secret morning. To serve or to upbraid, whether he could not tell, but scorned to beg her favour.

‘It is indeed, ma’am,’ Buck Mulligan said, pouring milk into their cups.

‘Taste it, sir,’ she said.

He drank at her bidding.

‘If we could only live on good food like that,’ he said to her somewhat loudly, ‘we wouldn’t have the country full of rotten teeth and rotten guts. Living in a bogswamp, eating cheap food and the streets paved with dust, horsedung and consumptives’ spits.’…………..

………Haines said to her, ‘Have you your bill? We had better pay her, Mulligan, hadn’t we?’………

…….‘Bill, sir?’ she said, halting. ‘Well, it’s seven mornings a pint at twopence is seven twos is a shilling and twopence over and these three mornings a quart at fourpence is three quarts is a shilling and one and two is two and two, sir.’……….

…….Stephen filled a third cup, a spoonful of tea colouring faintly the thick rich milk. Buck Mulligan brought up a florin (two shillings), twisted it round in his fingers and cried, ‘A miracle!’

He passed it along the table towards the old woman, saying, ‘Ask nothing more of me, sweet. All I can give you, I give.’

Stephen laid the coin in her uneager hand.

‘We’ll owe twopence,’ he said.

‘Time enough, sir,’ she said, taking the coin. ‘Time enough. Good morning, sir.’”

Calypso chapter

In the Calypso chapter of Part II, Mr Bloom’s desired meal of “thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hen-cod’s roe…….” and… “grilled mutton kidneys” have become world renowned menu items for any literary celebration of the novel and author.

A visit to Dlugacz’s pork butcher later in that chapter takes us back to a shopping scene of the times – with an added peek into Mr Bloom’s lecherous mind as he endeavours to follow a hip-swaying neighbour back to her home.

As he waits to complete his dealings with the butcher he is distracted by an advertisement on a meat-wrapping newspaper of a farm in Turkey. His mind wanders to the remote possibility of purchasing the farm for the purpose of growing trees!

On his return home, he observes the unproductive nature of his back garden – particularly its “scabby soil” which could be improved by “the hens in the next garden: their droppings are very good top-dressing. Best of all, though, are the cattle, especially when they are fed on those oil-cakes. Mulch of dung. Best thing to clean ladies’ kid gloves. Dirty cleans. Ashes too. Reclaim the whole place. Grow peas in that corner there. Lettuce. Always have fresh greens then.”

Draught-horses

Joyce observed the draught-horses used for dray and carriage work; as Mr Bloom approaches a cabman’s stand in the city.

“He came nearer and heard a crunching of gilded oats, the gently champing teeth. Their full buck eyes regarded him as he went by, amid the sweet oaten reek of horsepiss. Their El Dorado. Poor jugginses! Damn all they know or care about anything with their long noses stuck in nosebags. Too full for words. Still, they get their feed alright and their doss. Gelded too; a stump of black gutta-percha wagging limp between their haunches.. Might be happy all the same that way. Good poor brutes they look. Still, their ‘neigh’ can be very irritating.”

Hades chapter

A reference to the weather is made in the Hades chapter – “It’s as uncertain as a baby’s bottom,” (Mr Dedalus, Senior) said as he accompanies Mr Bloom to the Paddy Dignam burial in Glasnevin Cemetery.

As they traverse Dublin’s northside in the carriage, they encounter a mixture of cattle and sheep being herded through the streets for the boat to Liverpool.

“The carriage galloped round the corner. Stopped.

- What’s wrong now?

A divided drove of branded cattle passed the windows, lowing, slouching-by on padded hoofs, whisking their tails slowly on their clotted bony croups. Outside them and through them raddled sheep bleating their fear.

- Emigrants, Mr. Power said.

- Huuuh! The drover’s voice cried, his switch sounding on their flanks. Huuuh out of that!

Thursday, of course. Tomorrow is killing day. Springers. Cuffe sold them about twenty quid each. For Liverpool probably. Roast beef for old England. They buy up all the juicy ones. And then the fifth quarter is lost: all the raw stuff, hide, hair, horns. Comes to a big thing in a year. Dead meat trade. By-products of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine. Wonder if that dodge works now getting dicky meat off the train in Clonsilla.

The carriage moved on through the drove.

- I can’t make out why the Corporation doesn’t run a tramline from the park gate to the quays, Mr Bloom said. All those animals could be taken in trucks down to the boats.

- Instead of blocking up the thoroughfare, Martin Cunningham said. Quite right. They ought to.’”

Horse racing

An interesting horse-racing story wends its way through Ulysses; Mr Bloom, carrying a newspaper, is met by one Bantam Lyons, a follower of the “gee-gees”.

It is the day of the Ascot Gold Cup and Lyons requests a look at Bloom’s newspaper for the racing page. Mr Bloom offers it to him saying words to the effect that he was going to throw it away, anyway.

As it happens, a 20/1 outsider is running in the race called Throwaway and Lyons takes Bloom’s words as a tip. Throwaway wins on the day (and this can be checked on the internet for 16 June, 1904).

Mr Bloom has no interest in horse-racing, but word gets around that he has made a “packet” on the bet. When he fails to “stand” a drink to various acquaintances afterwards, he is deemed to be a bit of a “tight-wad” as the Americans would put it.

Food

These are some of the various farm/food connected references in this giant among novels.

From the nearby dairy farms of Ballymun, Dublin, of the ’50s I am now resident in my wife’s parish of Clonakilty, west Cork, where, if I look out through our back window, a dairy-farmland stretches for about 2km up to the loftily-positioned 100 hundred year established Darrara Agricultural College – and it is heaven!

Bloomsday takes place on 16 June.

Read more

From the Civil Service to crime thrillers

The man behind the words

SHARING OPTIONS