Over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British army during World War I; 35,000 of whom never came home.

Some were driven into the army by poverty and desperation. Some went to further the cause of Irish Home Rule. Many went out of loyalty to King.

At a recruiting rally early in the war, Colonel Morgan William O’Donovan, the hereditary chief of the ancient Gaelic family of O’Donovan of Clan Cathal, invoked ancient warrior traditions, reminding the people of Macroom that: “Every young Irishman is half a soldier already.”

His words were warmly received. The local regiment, the Royal Munster Fusiliers, was to raise 11 battalions over the course of the war, each consisting of roughly 1,000 men. The 2nd battalion was the first to go to France, and distinguished itself during the retreat from Mons and the first Battle of Ypres in 1914.

Appropriately for such a Catholic battalion, the Munsters aided in the evacuation of the Ypres Benedictine Convent, whose occupants subsequently established Kylemore Abbey in Connemara.

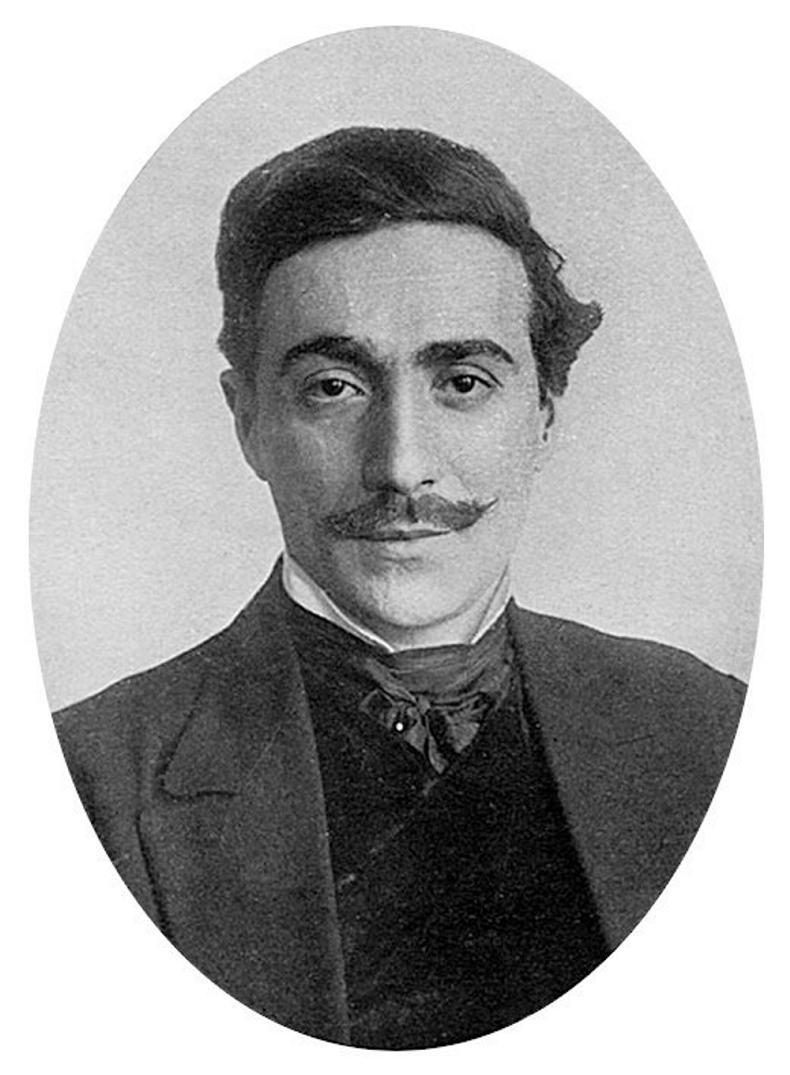

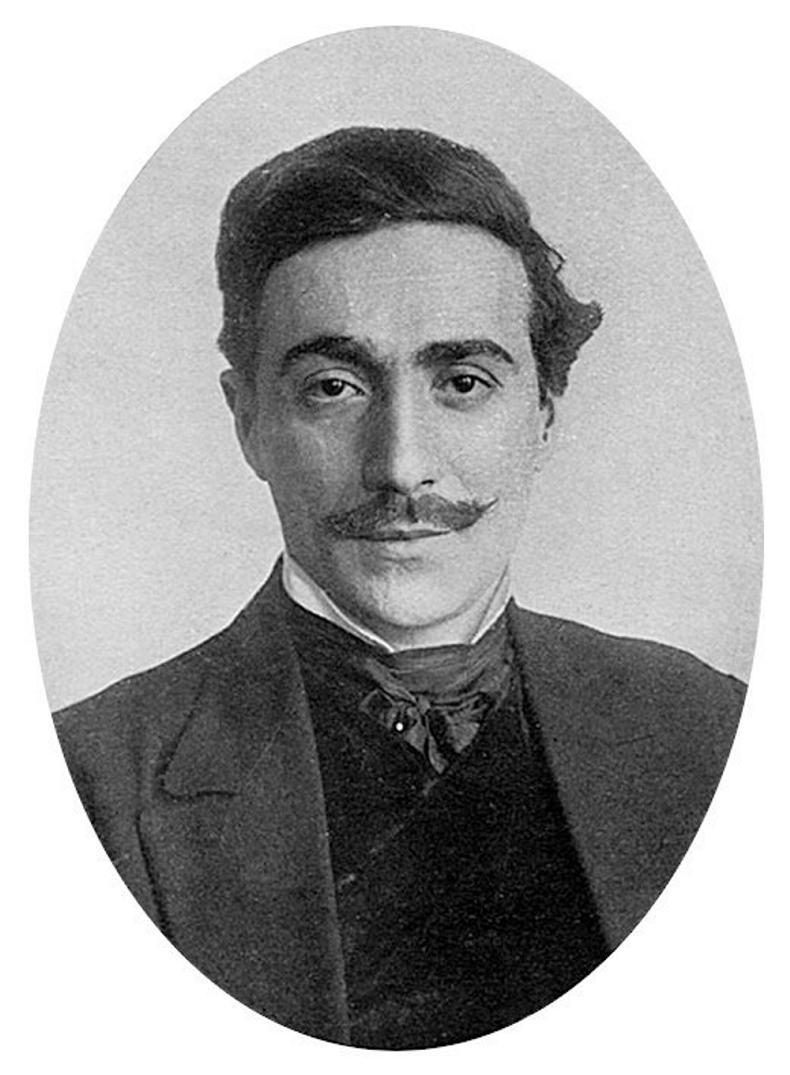

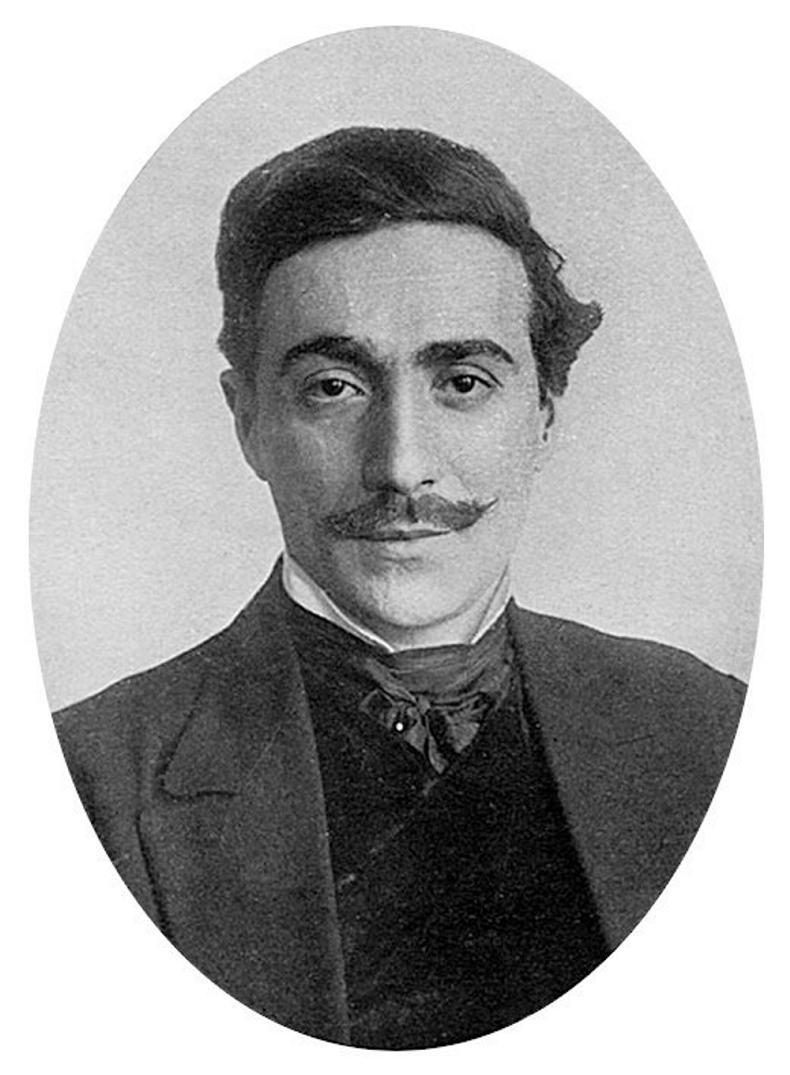

Fortunino Matania.

On 8 May the following year, the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers found itself marching to meet the enemy again, in what became known as the Battle of Aubers Ridge. At the battalion’s head rode its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Rickard, and its chaplain, Father Francis Gleeson, a native of Templemore. Marching down the Rue de Bois towards the frontline trenches, the battalion came upon an exposed altar amidst the ruins of a roadside church. It seemed an auspicious place to call a halt, and Father Gleeson granted the men of the 2nd Munsters a general absolution before the last leg of their journey.

The episode was to be immortalised by two remarkable artists. Colonel Rickard’s wife, Jesse, was a successful novelist and a regular contributor to the New Ireland newspaper. Her lyrical account of the Munsters’ experiences at Aubers Ridge was later reprinted by The Sphere, a London magazine illustrated by Fortunino Matania. Matania was an Italian-born artist noted for his realistic portrayal of a wide range of historical subjects. He based his haunting painting The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois on Jesse Rickard’s writings and the memories of Sergeant James Meehan, who had been present that evening. It was to become one of the most famous and most poignant works of art to come out of the war.

At 5am on 9 May 1915, British artillery commenced bombarding the German lines at Aubers Ridge in an effort to soften up the enemy defences before the main assault. The bombardment was almost wholly ineffective, and when the infantry left their trenches they were mown down by German machine guns.

Colonel Rickard was killed almost as soon as he set foot in no man’s land, but his men pressed on with extraordinary bravery and were briefly seen waving a green banner on the German breastworks.

Most of the other units engaged never even reached the enemy lines, and by 11am what remained of the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers was withdrawn.

Of the men who had received Father Gleeson’s absolution the previous evening, 151 lay dead and a further 220 were wounded. The attack was an unmitigated disaster for the British. No ground was won or tactical advantage gained, at a cost of 11,000 casualties.

In the account that Mrs Rickard wrote for New Ireland, she concluded: “So the Munsters came back after their day’s work; they formed up again in the Rue du Bois, numbering 200 men and three officers. It seems almost superfluous to make any further comment.”

Read more

Great Irish Paintings: The Battle of Aughrim

Great Irish Paintings: ‘The Biggest Walls in the Counthry was in it’ by Snaffles

Over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British army during World War I; 35,000 of whom never came home.

Some were driven into the army by poverty and desperation. Some went to further the cause of Irish Home Rule. Many went out of loyalty to King.

At a recruiting rally early in the war, Colonel Morgan William O’Donovan, the hereditary chief of the ancient Gaelic family of O’Donovan of Clan Cathal, invoked ancient warrior traditions, reminding the people of Macroom that: “Every young Irishman is half a soldier already.”

His words were warmly received. The local regiment, the Royal Munster Fusiliers, was to raise 11 battalions over the course of the war, each consisting of roughly 1,000 men. The 2nd battalion was the first to go to France, and distinguished itself during the retreat from Mons and the first Battle of Ypres in 1914.

Appropriately for such a Catholic battalion, the Munsters aided in the evacuation of the Ypres Benedictine Convent, whose occupants subsequently established Kylemore Abbey in Connemara.

Fortunino Matania.

On 8 May the following year, the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers found itself marching to meet the enemy again, in what became known as the Battle of Aubers Ridge. At the battalion’s head rode its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Rickard, and its chaplain, Father Francis Gleeson, a native of Templemore. Marching down the Rue de Bois towards the frontline trenches, the battalion came upon an exposed altar amidst the ruins of a roadside church. It seemed an auspicious place to call a halt, and Father Gleeson granted the men of the 2nd Munsters a general absolution before the last leg of their journey.

The episode was to be immortalised by two remarkable artists. Colonel Rickard’s wife, Jesse, was a successful novelist and a regular contributor to the New Ireland newspaper. Her lyrical account of the Munsters’ experiences at Aubers Ridge was later reprinted by The Sphere, a London magazine illustrated by Fortunino Matania. Matania was an Italian-born artist noted for his realistic portrayal of a wide range of historical subjects. He based his haunting painting The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois on Jesse Rickard’s writings and the memories of Sergeant James Meehan, who had been present that evening. It was to become one of the most famous and most poignant works of art to come out of the war.

At 5am on 9 May 1915, British artillery commenced bombarding the German lines at Aubers Ridge in an effort to soften up the enemy defences before the main assault. The bombardment was almost wholly ineffective, and when the infantry left their trenches they were mown down by German machine guns.

Colonel Rickard was killed almost as soon as he set foot in no man’s land, but his men pressed on with extraordinary bravery and were briefly seen waving a green banner on the German breastworks.

Most of the other units engaged never even reached the enemy lines, and by 11am what remained of the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers was withdrawn.

Of the men who had received Father Gleeson’s absolution the previous evening, 151 lay dead and a further 220 were wounded. The attack was an unmitigated disaster for the British. No ground was won or tactical advantage gained, at a cost of 11,000 casualties.

In the account that Mrs Rickard wrote for New Ireland, she concluded: “So the Munsters came back after their day’s work; they formed up again in the Rue du Bois, numbering 200 men and three officers. It seems almost superfluous to make any further comment.”

Read more

Great Irish Paintings: The Battle of Aughrim

Great Irish Paintings: ‘The Biggest Walls in the Counthry was in it’ by Snaffles

SHARING OPTIONS