Changing topics from field to fowl during the ITLUS tour to Australia in 2020, we had a very interesting visit to Canobolas Eggs near Molong in New South Wales.

Here, we met with Rob Peffer, who told us that the business was set up by his grandparents and that he was involved for the past 11 years at that point.

The farm has an area of crops, but there was little doubt that laying hens are now the major focus.

The business continues to expand in egg production and the oldest building used now was built in 1988.

Rob Peffer of Canololas Eggs explains the workings of the poultry farm.

Working with his uncles and cousins, the number of laying hens has been increased in recent times from around 100,000 to 220,000 birds per year.

They consume up to 160t of feed per week and the farm now has its own mill on site.

This was a very impressive visit and the first visit to a poultry farm I had even managed to organise in the 30 years of ITLUS tours.

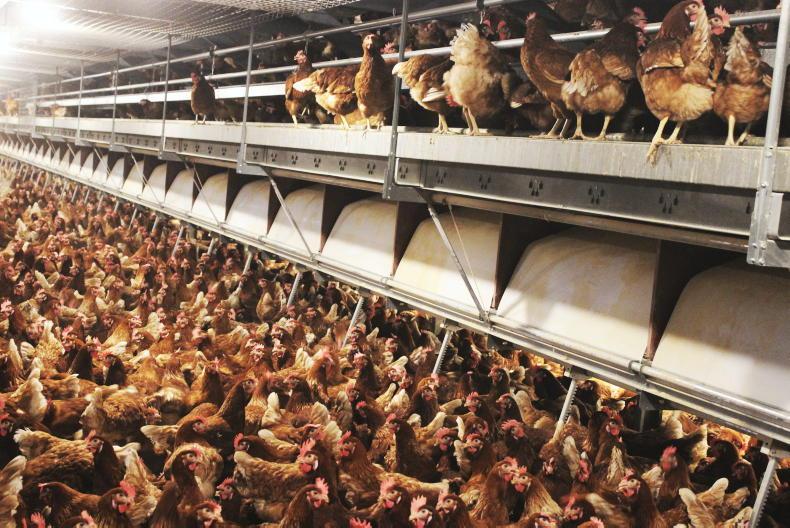

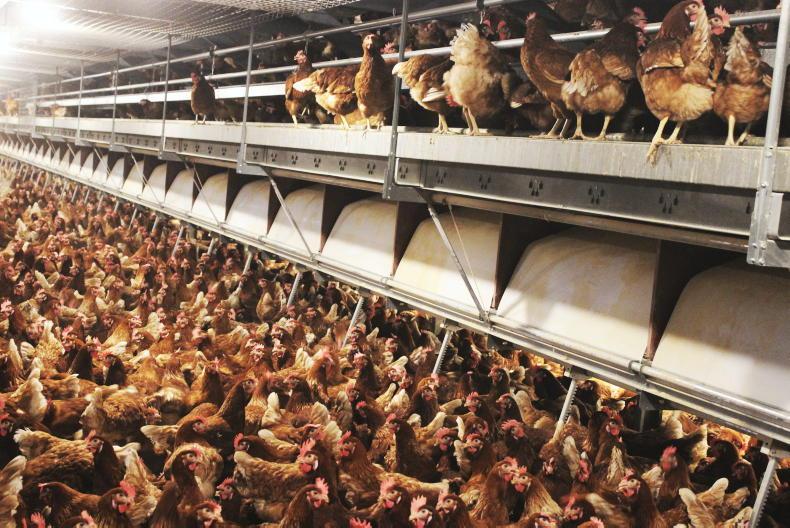

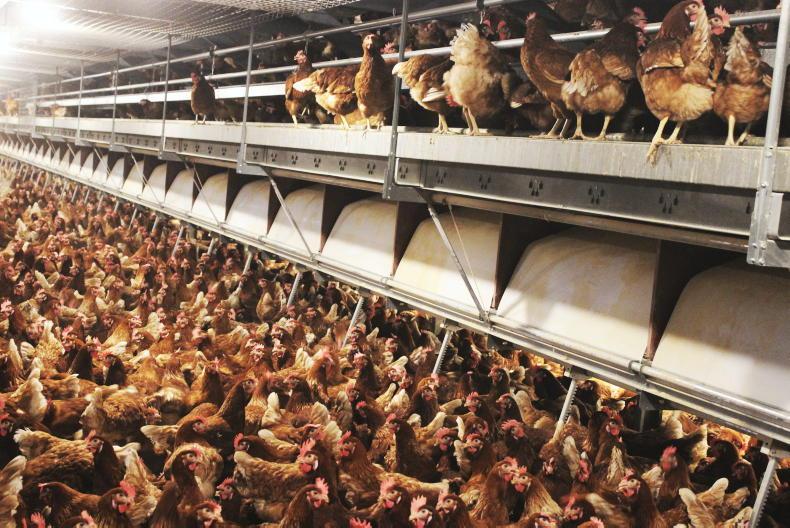

A portion of the laying flock are reared in cages and fed by automatic feeders. The eggs roll out under the birds and are gathered automatically on belts.

That said, biosecurity is still very important to the farm.

Before we visited, I had to provide an itinerary of where we had been in the five preceding days and one other proposed visit had to be cancelled because we had visited Canobolas.

Wells were dry

When we visited in January 2020, the effects of the prolonged drought were serious and plain to be seen. Rob said it was the worst drought on record in that area and three of the five wells they use for their business were dry.

Having finished his harvest well before we visited, Rob reported that his wheat had yielded 2.1t/ha and some barley crops did up to 2.6t/ha, but much of it only did 1t/ha and some of it was not worth cutting.

Expansion and biosecurity

Expansion is a challenge because of the need for biosecurity with incoming stock.

That means that the capacity to access laying hens is governed by the farm’s rearing capacity for chicks.

Rob explained that salmonella is a big concern everywhere and that Asian bird flu caused a 3% cull in hen numbers in Australia in just one week.

So care bringing new birds on to the farm is of paramount importance.

Birds are bought in as day-old chicks and reared in cages in specialised rearing houses.

In this, the cages can be altered in height, so as to get the birds accustomed to the varying heights they will experience in the laying houses.

He also commented that if a young bird stays on the ground for too long, they may not lay at all later in life and these can actually begin to fade away.

Egg sorting and packing at Canobolas Eggs.

New birds spend the first 14 weeks of their lives in the specialised isolated rearing unit on the farm.

They are then moved to disinfected laying houses and begin to lay at 15 to 16 weeks of age.

Chicks for replacement stock are ordered four years ahead of requirement and the capacity of the farm is limited by the supply of birds through the rearing house.

Facilities and systems

The farm uses a combination of cage, barn and free-range housing systems for its egg production. Rob commented that every system has its pros and cons and that it is important for people to understand this.

A view of part of a section of the multi-level free-range laying house.

Cages are more feed efficient, while free range is least feed efficient and much less biosecure.

Cages have a lower mortality rate, which is higher in free range.

A recent lightning storm had caused significant chicken deaths in his free-range yard.

He also said that an iguana got into a free-range compound once and caused considerable bird deaths.

However, he also said that all the other birds may as well have died because they never really recovered from the trauma.

Mortality

Mortality in the cages is about 3% to 3.5% versus 5% to 8% in the free-range system.

However, he said that mortality in some batches of free-range birds can be as high as 20%.

He uses no antibiotics in the cages, but does have to use some in the free-range system.

Based on his experience, he does not see free range as being the only viable option for egg production going forward.

Canobolas produces between 53 and 54 million eggs per year, which equates to about 245 eggs per bird per year.

They begin to lay at 15 to 16 weeks of age having come out of the rearing house and continue to lay for about a further 60 weeks.

He is currently trying to push out the productive life of the laying birds to 70 weeks to help overall efficiency.

The specialised chick reading facility at Canobolas Eggs.

Given that a major limitation to production is getting chicks reared to laying age, prolonging the life of the laying birds is important to increasing throughput.

Some batches have already been laying for 65 weeks and were on 93% laying rate.

Even if the laying rate were to drop to 85% at 70 weeks laying, Rob estimated that this would be more than sufficient to justify the increased longevity. At that point, the hens would be 84 weeks of age.

End-of-life birds have no salvage value to the business. There are very few neighbours looking for a few hens, indeed there are very few neighbours and if there were, he would sell fewer eggs. When they are finished laying, they are just used for rendering and have no value to him.

Markets and marketing

Distance is a major influence in terms of where eggs can be produced. A producer must really be within a maximum of four hours’ drive of a major city for a range of logistical reasons.

Rob was not very complimentary of the Australian retail system. He said that the grower gets 30% to 55% of the retail price, while one particular retailer is getting 45% for a miniscule amount of the time and investment - “unethical and immoral,” he stated.

His last price increase was in 2014 and that only brought prices back up to the levels which they had been at in 2004.

Costs have increased in the interim and therefore margins have fallen. Sound familiar?

Rob tries to have a market for 80% of his produce to help cope with the peaks and troughs in the market.

The industry is not organised, so producers must negotiate individually for their business with the major outlets.

Payment is on a 60- to 90-day credit basis and he emphasised the importance of doing business with more than one retailer.

Changing topics from field to fowl during the ITLUS tour to Australia in 2020, we had a very interesting visit to Canobolas Eggs near Molong in New South Wales.

Here, we met with Rob Peffer, who told us that the business was set up by his grandparents and that he was involved for the past 11 years at that point.

The farm has an area of crops, but there was little doubt that laying hens are now the major focus.

The business continues to expand in egg production and the oldest building used now was built in 1988.

Rob Peffer of Canololas Eggs explains the workings of the poultry farm.

Working with his uncles and cousins, the number of laying hens has been increased in recent times from around 100,000 to 220,000 birds per year.

They consume up to 160t of feed per week and the farm now has its own mill on site.

This was a very impressive visit and the first visit to a poultry farm I had even managed to organise in the 30 years of ITLUS tours.

A portion of the laying flock are reared in cages and fed by automatic feeders. The eggs roll out under the birds and are gathered automatically on belts.

That said, biosecurity is still very important to the farm.

Before we visited, I had to provide an itinerary of where we had been in the five preceding days and one other proposed visit had to be cancelled because we had visited Canobolas.

Wells were dry

When we visited in January 2020, the effects of the prolonged drought were serious and plain to be seen. Rob said it was the worst drought on record in that area and three of the five wells they use for their business were dry.

Having finished his harvest well before we visited, Rob reported that his wheat had yielded 2.1t/ha and some barley crops did up to 2.6t/ha, but much of it only did 1t/ha and some of it was not worth cutting.

Expansion and biosecurity

Expansion is a challenge because of the need for biosecurity with incoming stock.

That means that the capacity to access laying hens is governed by the farm’s rearing capacity for chicks.

Rob explained that salmonella is a big concern everywhere and that Asian bird flu caused a 3% cull in hen numbers in Australia in just one week.

So care bringing new birds on to the farm is of paramount importance.

Birds are bought in as day-old chicks and reared in cages in specialised rearing houses.

In this, the cages can be altered in height, so as to get the birds accustomed to the varying heights they will experience in the laying houses.

He also commented that if a young bird stays on the ground for too long, they may not lay at all later in life and these can actually begin to fade away.

Egg sorting and packing at Canobolas Eggs.

New birds spend the first 14 weeks of their lives in the specialised isolated rearing unit on the farm.

They are then moved to disinfected laying houses and begin to lay at 15 to 16 weeks of age.

Chicks for replacement stock are ordered four years ahead of requirement and the capacity of the farm is limited by the supply of birds through the rearing house.

Facilities and systems

The farm uses a combination of cage, barn and free-range housing systems for its egg production. Rob commented that every system has its pros and cons and that it is important for people to understand this.

A view of part of a section of the multi-level free-range laying house.

Cages are more feed efficient, while free range is least feed efficient and much less biosecure.

Cages have a lower mortality rate, which is higher in free range.

A recent lightning storm had caused significant chicken deaths in his free-range yard.

He also said that an iguana got into a free-range compound once and caused considerable bird deaths.

However, he also said that all the other birds may as well have died because they never really recovered from the trauma.

Mortality

Mortality in the cages is about 3% to 3.5% versus 5% to 8% in the free-range system.

However, he said that mortality in some batches of free-range birds can be as high as 20%.

He uses no antibiotics in the cages, but does have to use some in the free-range system.

Based on his experience, he does not see free range as being the only viable option for egg production going forward.

Canobolas produces between 53 and 54 million eggs per year, which equates to about 245 eggs per bird per year.

They begin to lay at 15 to 16 weeks of age having come out of the rearing house and continue to lay for about a further 60 weeks.

He is currently trying to push out the productive life of the laying birds to 70 weeks to help overall efficiency.

The specialised chick reading facility at Canobolas Eggs.

Given that a major limitation to production is getting chicks reared to laying age, prolonging the life of the laying birds is important to increasing throughput.

Some batches have already been laying for 65 weeks and were on 93% laying rate.

Even if the laying rate were to drop to 85% at 70 weeks laying, Rob estimated that this would be more than sufficient to justify the increased longevity. At that point, the hens would be 84 weeks of age.

End-of-life birds have no salvage value to the business. There are very few neighbours looking for a few hens, indeed there are very few neighbours and if there were, he would sell fewer eggs. When they are finished laying, they are just used for rendering and have no value to him.

Markets and marketing

Distance is a major influence in terms of where eggs can be produced. A producer must really be within a maximum of four hours’ drive of a major city for a range of logistical reasons.

Rob was not very complimentary of the Australian retail system. He said that the grower gets 30% to 55% of the retail price, while one particular retailer is getting 45% for a miniscule amount of the time and investment - “unethical and immoral,” he stated.

His last price increase was in 2014 and that only brought prices back up to the levels which they had been at in 2004.

Costs have increased in the interim and therefore margins have fallen. Sound familiar?

Rob tries to have a market for 80% of his produce to help cope with the peaks and troughs in the market.

The industry is not organised, so producers must negotiate individually for their business with the major outlets.

Payment is on a 60- to 90-day credit basis and he emphasised the importance of doing business with more than one retailer.

SHARING OPTIONS