The stark difference in the level of transparency in the beef and dairy sector is obvious in this week’s paper. We carry the KPMG/Irish Farmers Journal milk price review this week along with a detailed analysis of the financial performance of each milk processor.

The cooperative nature of our dairy processing structure sees each processor engage in this annual price review on a voluntary basis.

It is a familiar trend with the four west Cork co-ops dominating the top of the table. Returning an average price of 36.95c/l, after deductions and levies, Barryroe is back on top. It is a phenomenal performance with the co-op having returned the top milk price to its suppliers in six of the last 10 years. The strength of the Carbery model, under which the four west Cork co-ops trade, is evident by the fact that the price returned in 2018 was 2.5c/l ahead of big-volume players, mainly Glanbia and Dairygold.

In the case of Glanbia, the figures used in the Irish Farmers Journal analysis have been revised downwards by 0.5c/l from the Glanbia price as reviewed by KMPG. This reflects the fact that, on the basis that technically both schemes are paid on a c/l basis, the Glanbia price, as reviewed by KPMG, includes the trading and loyalty bonuses paid to suppliers in line with the current definition.

The Irish Farmers Journal believes both schemes are outside the scope of the definition as they are payments for trade related to the business and not manufacturing milk, per se. We view the inclusion of such schemes in the Milk Price Review as threatening the integrity of the league and negatively affecting milk price transparency. KPMG and the Irish Farmers Journal have agreed to clarify the definition to ensure such schemes are excluded in future years.

While factories claim to be incurring losses, farmers have zero insight into whether this is the case

Meanwhile, the profit warning issued by Glanbia plc earlier this week will be of serious concern to Glanbia suppliers. The announcement may see the dividend that goes from the plc to the co-op – used to support milk price – become more challenging in future years. Questions are also likely to be asked of the group’s investment strategy. Eoin Lowry goes into detail here.

At the opposite end of the table, we see Arrabawn and Aurivo returning a milk price equivalent to €191 and €202 per cow less than Barryroe. When assessing the performance of any co-op, the range of services and the geographical spread of suppliers needs to be taken into account. Aurivo, with a low-margin marts business and a supplier base spanning 14 counties, has a number of specific business and regional challenges.

The fact that the two co-ops at the bottom of the manufacturing milk price table process significant volumes of liquid milk raises the question as to the level of cross subsidisation taking place. Has the value within the liquid milk market been eroded to such an extent that it is now a drain on these businesses?

The liquid milk market is the one market where farmers should have been in a strong position to protect their margins from retailers. Yet a combination of supplying retailers with own label product and co-ops competing with each other on price has seen margin disappear.

While important, milk price is not the only indicator on which to measure the performance of a co-op. It should be assessed against the financial performance of the business, the trend in debt levels and ongoing investments. We detail the five-year trends for each here.

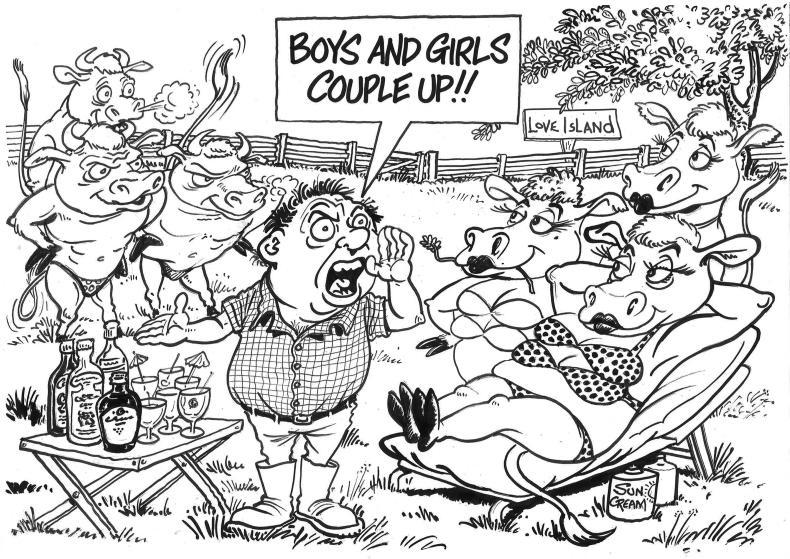

The level of insight into the dairy sector is in stark contrast to beef. Farmers have seen the market collapse with finished cattle falling 17c/kg in just three weeks. While factories claim, even at current prices, to be incurring losses, farmers have zero insight into whether this is the case. It is this cloud that has this week seen farmers standing at the gates of beef factories across the country. As Phelim O’Neill reports, all we know is that the price fall in Ireland in has outpaced our main export markets.

Meanwhile, the IFA has turned its sights on the EU Food and Veterinary Office in a bid to apply further pressure on the European Commission to suspend South American beef imports. Calling for a suspension on South American imports at a time when the EU market is facing major disturbance from Brexit is a legitimate request from Irish farmers.

Brexit: farmers need war chest to combat Boris Johnson’s war cabinet

UK prime minister Boris Johnson. \ REUTERS/Darren Staples

UK prime minister Boris Johnson does not appear concerned about reaching a Brexit deal with the EU. His travel plans and narrative since taking office point to a prime minister focused on preparing for a general election. His hard-hitting words and defiant stance on the withdrawal agreement are not aimed at the EU or indeed Ireland. They are very much aimed at winning back the large swathes of Conservative voters who shifted support towards Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party in the European elections.

Johnson is banking on the fact that a no-deal Brexit will be rejected by Parliament. This gives him the comfort of being able to play the populist card and take negotiations to the wire, knowing that when unsuccessful he has a safety net in place.

The obvious follow-on is for the Johnson administration to call a general election in the hope that they will secure a majority that will remove the DUP influence. Such a move would clear the political landscape for sensible discussion around a border in the Irish Sea.

In the meantime, farmers on the island of Ireland will continue to be political pawns in the Johnson strategy. Currency volatility and disruption to normal trade flows are clearly having a serious impact on farm incomes.

Neither the Government nor the European Commission can ignore the ongoing financial crisis on Irish farms. As we report this week, farmers across the country are fighting numerous battles under different banners to highlight the impact on their income. But does this provide the best chance of securing a successful outcome or does a divided farming community actually let politicians off the hook?

Is it beyond our ambition to park farming politics and, with one voice, demand that the Government and the Commission put in place a “war chest” that does not allow Johnson’s “war cabinet” to use Irish farmers as political pawns.

It is an important period for the sheep sector. In the coming weeks, lamb throughput will peak and breeding sales will get into full swing. An increasing number of suckler farmers are looking to sheep as a viable alternative, both in terms of profitability and to reduce exposure to Brexit. Darren Carty will provide detailed coverage and analysis of the trade as it develops in print and online.

Fertilising: using poultry litter on tillage farms

There are 145,000 tonnes of poultry litter produced each year in Ireland. It is a nutrient-rich, high dry matter product that can play an important role in reducing the use of chemical fertiliser on tillage farms while at the same time increasing soil organic matter.

The challenge arrives when it comes to dealing with the risk of botulism. Also this week, Andy Doyle looks at what steps should be taken to reduce this risk.

All parts of the supply chain – from the poultry farmer to the tillage farmer – have a role to play.

At each stage of the process, all guidelines must be adhered to if we are to ensure this valuable resource can continue to be utilised while at the same time reducing the risks to the livestock sector.

This week’s Focus is on reseeding. After a good summer for grass growth over most of the country, this autumn will be a good opportunity to get some underperforming fields reseeded.

The cost of reseeding is over €300/acre, but the payback period from reseeding underperforming paddocks has consistently been put at less than two years, making it one of the best on-farm investments available.

As Aidan Brennan rightly points out, good grazing management and correct soil fertility are the keys to getting a long life from new reseeds. In too many cases, we see a reseeded field revert back to old weed grasses after only a few years.

It is good to see the increased interest in over-sowing clover and to see Teagasc trials on clover continuing. While the environmental and animal performance benefits are without question, we as farmers still have a lot to learn about how to manage it correctly.

The stark difference in the level of transparency in the beef and dairy sector is obvious in this week’s paper. We carry the KPMG/Irish Farmers Journal milk price review this week along with a detailed analysis of the financial performance of each milk processor.

The cooperative nature of our dairy processing structure sees each processor engage in this annual price review on a voluntary basis.

It is a familiar trend with the four west Cork co-ops dominating the top of the table. Returning an average price of 36.95c/l, after deductions and levies, Barryroe is back on top. It is a phenomenal performance with the co-op having returned the top milk price to its suppliers in six of the last 10 years. The strength of the Carbery model, under which the four west Cork co-ops trade, is evident by the fact that the price returned in 2018 was 2.5c/l ahead of big-volume players, mainly Glanbia and Dairygold.

In the case of Glanbia, the figures used in the Irish Farmers Journal analysis have been revised downwards by 0.5c/l from the Glanbia price as reviewed by KMPG. This reflects the fact that, on the basis that technically both schemes are paid on a c/l basis, the Glanbia price, as reviewed by KPMG, includes the trading and loyalty bonuses paid to suppliers in line with the current definition.

The Irish Farmers Journal believes both schemes are outside the scope of the definition as they are payments for trade related to the business and not manufacturing milk, per se. We view the inclusion of such schemes in the Milk Price Review as threatening the integrity of the league and negatively affecting milk price transparency. KPMG and the Irish Farmers Journal have agreed to clarify the definition to ensure such schemes are excluded in future years.

While factories claim to be incurring losses, farmers have zero insight into whether this is the case

Meanwhile, the profit warning issued by Glanbia plc earlier this week will be of serious concern to Glanbia suppliers. The announcement may see the dividend that goes from the plc to the co-op – used to support milk price – become more challenging in future years. Questions are also likely to be asked of the group’s investment strategy. Eoin Lowry goes into detail here.

At the opposite end of the table, we see Arrabawn and Aurivo returning a milk price equivalent to €191 and €202 per cow less than Barryroe. When assessing the performance of any co-op, the range of services and the geographical spread of suppliers needs to be taken into account. Aurivo, with a low-margin marts business and a supplier base spanning 14 counties, has a number of specific business and regional challenges.

The fact that the two co-ops at the bottom of the manufacturing milk price table process significant volumes of liquid milk raises the question as to the level of cross subsidisation taking place. Has the value within the liquid milk market been eroded to such an extent that it is now a drain on these businesses?

The liquid milk market is the one market where farmers should have been in a strong position to protect their margins from retailers. Yet a combination of supplying retailers with own label product and co-ops competing with each other on price has seen margin disappear.

While important, milk price is not the only indicator on which to measure the performance of a co-op. It should be assessed against the financial performance of the business, the trend in debt levels and ongoing investments. We detail the five-year trends for each here.

The level of insight into the dairy sector is in stark contrast to beef. Farmers have seen the market collapse with finished cattle falling 17c/kg in just three weeks. While factories claim, even at current prices, to be incurring losses, farmers have zero insight into whether this is the case. It is this cloud that has this week seen farmers standing at the gates of beef factories across the country. As Phelim O’Neill reports, all we know is that the price fall in Ireland in has outpaced our main export markets.

Meanwhile, the IFA has turned its sights on the EU Food and Veterinary Office in a bid to apply further pressure on the European Commission to suspend South American beef imports. Calling for a suspension on South American imports at a time when the EU market is facing major disturbance from Brexit is a legitimate request from Irish farmers.

Brexit: farmers need war chest to combat Boris Johnson’s war cabinet

UK prime minister Boris Johnson. \ REUTERS/Darren Staples

UK prime minister Boris Johnson does not appear concerned about reaching a Brexit deal with the EU. His travel plans and narrative since taking office point to a prime minister focused on preparing for a general election. His hard-hitting words and defiant stance on the withdrawal agreement are not aimed at the EU or indeed Ireland. They are very much aimed at winning back the large swathes of Conservative voters who shifted support towards Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party in the European elections.

Johnson is banking on the fact that a no-deal Brexit will be rejected by Parliament. This gives him the comfort of being able to play the populist card and take negotiations to the wire, knowing that when unsuccessful he has a safety net in place.

The obvious follow-on is for the Johnson administration to call a general election in the hope that they will secure a majority that will remove the DUP influence. Such a move would clear the political landscape for sensible discussion around a border in the Irish Sea.

In the meantime, farmers on the island of Ireland will continue to be political pawns in the Johnson strategy. Currency volatility and disruption to normal trade flows are clearly having a serious impact on farm incomes.

Neither the Government nor the European Commission can ignore the ongoing financial crisis on Irish farms. As we report this week, farmers across the country are fighting numerous battles under different banners to highlight the impact on their income. But does this provide the best chance of securing a successful outcome or does a divided farming community actually let politicians off the hook?

Is it beyond our ambition to park farming politics and, with one voice, demand that the Government and the Commission put in place a “war chest” that does not allow Johnson’s “war cabinet” to use Irish farmers as political pawns.

It is an important period for the sheep sector. In the coming weeks, lamb throughput will peak and breeding sales will get into full swing. An increasing number of suckler farmers are looking to sheep as a viable alternative, both in terms of profitability and to reduce exposure to Brexit. Darren Carty will provide detailed coverage and analysis of the trade as it develops in print and online.

Fertilising: using poultry litter on tillage farms

There are 145,000 tonnes of poultry litter produced each year in Ireland. It is a nutrient-rich, high dry matter product that can play an important role in reducing the use of chemical fertiliser on tillage farms while at the same time increasing soil organic matter.

The challenge arrives when it comes to dealing with the risk of botulism. Also this week, Andy Doyle looks at what steps should be taken to reduce this risk.

All parts of the supply chain – from the poultry farmer to the tillage farmer – have a role to play.

At each stage of the process, all guidelines must be adhered to if we are to ensure this valuable resource can continue to be utilised while at the same time reducing the risks to the livestock sector.

This week’s Focus is on reseeding. After a good summer for grass growth over most of the country, this autumn will be a good opportunity to get some underperforming fields reseeded.

The cost of reseeding is over €300/acre, but the payback period from reseeding underperforming paddocks has consistently been put at less than two years, making it one of the best on-farm investments available.

As Aidan Brennan rightly points out, good grazing management and correct soil fertility are the keys to getting a long life from new reseeds. In too many cases, we see a reseeded field revert back to old weed grasses after only a few years.

It is good to see the increased interest in over-sowing clover and to see Teagasc trials on clover continuing. While the environmental and animal performance benefits are without question, we as farmers still have a lot to learn about how to manage it correctly.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: