According to European Commissioner for Trade Phil Hogan, the EU will adopt a Brian Cody approach when it comes to taking on the challenges of global trade: play to our strengths, improve our defence, go after our target and not be afraid of a little ground hurling. Hogan used the analogy in Dublin last week when outlining to business leaders how EU trade policy would respond to what is a much more hostile global trading environment.

The presentation struck a more aggressive tone than we have traditionally seen from Brussels, with Hogan taking aim at China and the UK.

China was accused of “making a mockery of level playing fields and fair, rule-based trade” through its exploitation of gaps in the international rule book to further its consolidation of global power.

Meanwhile, in a clear reference to attempts by UK prime minister Boris Johnson to renege on aspects of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement, Hogan warned that “if the UK wants to be taken seriously when forging other trade deals around the world, it has to honour its commitments”.

Interestingly, as he prepares to travel across the Atlantic again, Hogan’s comments regarding the US were much more measured – he spoke of “small and slow steps” being taken towards a “mini deal”.

Worryingly for farmers, when Hogan last visited the US in January, he is reported as having indicated that the EU was willing to entertain new concessions on agricultural standards to break the current impasse. The move to concede to the US on standards in food safety and animal health comes despite Hogan stating in Dublin last week that the EU was leading the way globally on standards and climate change, and that “when we sign trade agreements, we expect our partners to meet our standards”.

GM technologies are banned and yet imported product using them determine the market price returned to farmers

It is this contradiction between what is said and the actions taken that undermines EU policy. Within the context of the EU, it is a fair reflection when Hogan talks about the EU being the global “standard setter”. But what protection does being a standard setter afford EU farmers if standards in relation to food safety, animal welfare and climate change are not applied equally to international trade?

An uneven playing field means farmers can neither compete on international markets nor against imports in the domestic market. The EU tillage sector is a case in point, where GM technologies are banned and yet imported product using these technologies determine the market price returned to farmers.

International trade is no longer being developed through rules-based bilateral or multilateral agreements. The preferred option now is to use trade wars and punitive tariffs against trade rivals to get what is desired.

In this environment, the financial impact of these tariffs carries more weight than the alignment of standards when trying to reach a trading agreement.

Given the global political landscape and the move towards populist national agendas, it is a trend that is unlikely to change. It is also a trend that will go unchallenged while the WTO’s appellate body (its appeals mechanism) remains shut down. The undermining of the WTO by China and the retaliatory action by the Trump administration to pull down the appellate body has neutered the WTO’s ability to police global trade.

It is this lawless global trading landscape that has seen the EU discharge its tough-talking trade commissioner in a bid to protect Europe’s economic interests. But while Hogan’s approach is getting traction, talking will only go so far. The most immediate indication as to whether the EU is prepared to back it up with tough actions will be the extent to which it rewards Donald Trump’s policy of trade wars and ripping up the Paris climate agreement by conceding on EU standards to reach a “mini deal”.

The second test will be the EU’s financial support for CAP. Slashing supports to “standard-setting” farmers faced with the headwinds of a global market where rules no longer apply and standards appear to be a tradeable commodity is at odds with the commissioner’s hard-hitting narrative. Reducing farmer support by €54bn hardly constitutes “playing to our strengths” or “improving our defence”. Nor would continuing with a Mercosur deal where the rules of trade are clearly being ignored.

Perhaps it is time Hogan started playing a bit of ground hurling back in Brussels to ensure policy direction is aligned to his tough talking.

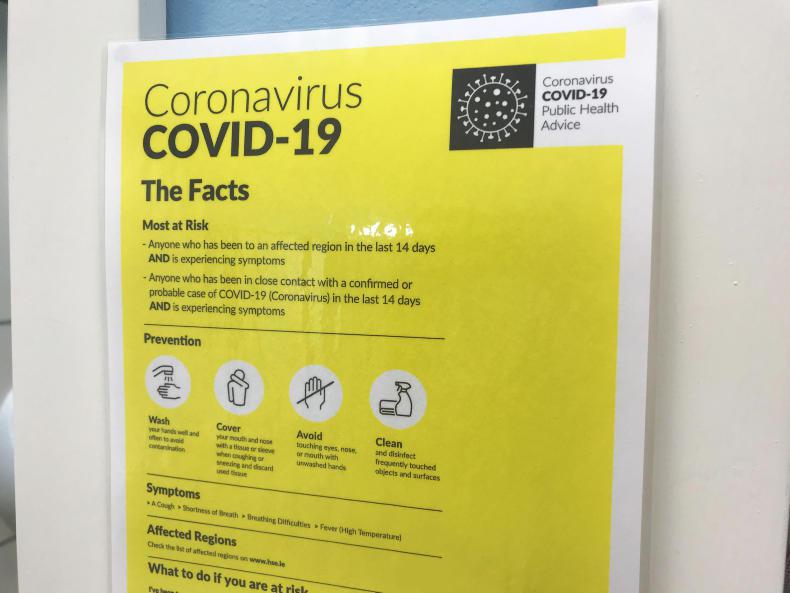

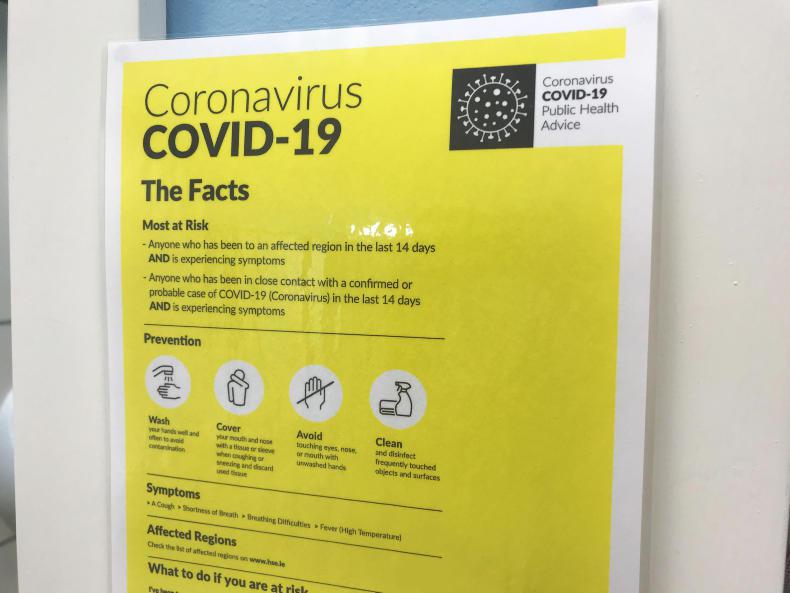

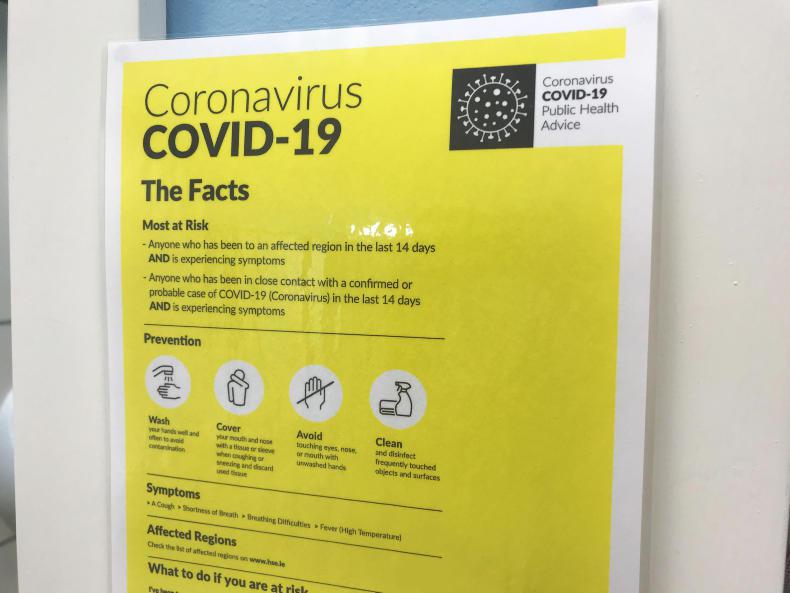

Coronavirus: working together in uncertain times

In this week’s edition, we look at plans being put in place across the industry to try to minimise the impact of COVID-19. Should the infection spread to the extent that some are forecasting, the challenge will be availability of labour to operate processing facilities and maintain supply chains.

It is encouraging not only to see that contingency planning is well advanced but also the level of collaboration taking place across the industry to limit disruption. It is important that the necessary regulatory scope, outside of food safety, is provided to allow business the flexibility to adjust to this evolving situation.

At this stage, the impact on demand and market prices is largely unknown but it is unlikely to be positive. In the same way as Government has rightly announced a necessary package of reforms for sick pay, illness benefit and supplementary benefit, it must also stand ready to support farm incomes should the need arise.

The option of introducing an aid to private storage scheme or programmes that remove product should the supply chains be disrupted should be under consideration. While hopefully neither will be required, advance planning should still be taking place in the background. In line with concessions granted to the Italian government, any emergency measures should be allowed operate outside of Brussels’ fiscal and state-aid rules.

Meanwhile, our specialist team outline practical steps that farmers can take to ensure disruption to the farm is minimised in the period ahead and – most importantly – the steps to reduce the risk of the infection to family members.

Coronavirus: managing risk

We are assured that the coronavirus is spread person-to-person and is not a food-borne illness. By far the biggest risk to the meat and milk processing sectors is the threat of the virus affecting staff and subsequently the ability of milk processors to make cheese, powder or carry out simple tasks like basic pasteurisation or collection of milk.

Processors are working hard behind the scenes. Staff that can do multiple tasks may need to be called into other parts of the business. Is there a need to create a national processing team? By this I mean a team of individuals with the necessary experience and flexibility that could travel at short notice to a processor who finds out that 20, 30 or 40% of their processing team are out of action.

This may mean processors have to leave aside any differences so that a certain level of specialised personnel cover is created for what has been deemed a State-critical industry.

Appointment: Declan Marren joins our livestock team

We are delighted to welcome Dr Declan Marren on to our livestock team. Declan joined the Irish Farmers Journal in 2017 and has led our Farm Profitability Programme in Scotland since then. Back in Ireland, Declan will lead our Thrive programme, which aims to identify best practice technologies in dairy calf-to-beef systems.

He will oversee the management of our dairy beef demonstration farm in Cashel, Co Tipperary, and work closely with our demonstration farmers around the country.

Declan, who hails from a suckler and sheep farm in Co Sligo, holds a PhD from Teagasc Grange on beef production systems.

Tillage: crux time for cereal seed supply

Pressures on the requirement for certified spring barley seed could cause significant problems if we do not get a mix of crops planted this spring.

The ongoing bad weather that has prevented normal planting patterns will lead to an inevitable scarcity of certified seed of spring barley is this becomes the default crop when planting gets underway. Growers are advised to secure seed and also be aware of the need to get other crops like spring wheat and beans planted to ease the pressure. This scarcity is exacerbated due to the bad weather experienced across much of northern Europe which prevented winter crop planting.

According to European Commissioner for Trade Phil Hogan, the EU will adopt a Brian Cody approach when it comes to taking on the challenges of global trade: play to our strengths, improve our defence, go after our target and not be afraid of a little ground hurling. Hogan used the analogy in Dublin last week when outlining to business leaders how EU trade policy would respond to what is a much more hostile global trading environment.

The presentation struck a more aggressive tone than we have traditionally seen from Brussels, with Hogan taking aim at China and the UK.

China was accused of “making a mockery of level playing fields and fair, rule-based trade” through its exploitation of gaps in the international rule book to further its consolidation of global power.

Meanwhile, in a clear reference to attempts by UK prime minister Boris Johnson to renege on aspects of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement, Hogan warned that “if the UK wants to be taken seriously when forging other trade deals around the world, it has to honour its commitments”.

Interestingly, as he prepares to travel across the Atlantic again, Hogan’s comments regarding the US were much more measured – he spoke of “small and slow steps” being taken towards a “mini deal”.

Worryingly for farmers, when Hogan last visited the US in January, he is reported as having indicated that the EU was willing to entertain new concessions on agricultural standards to break the current impasse. The move to concede to the US on standards in food safety and animal health comes despite Hogan stating in Dublin last week that the EU was leading the way globally on standards and climate change, and that “when we sign trade agreements, we expect our partners to meet our standards”.

GM technologies are banned and yet imported product using them determine the market price returned to farmers

It is this contradiction between what is said and the actions taken that undermines EU policy. Within the context of the EU, it is a fair reflection when Hogan talks about the EU being the global “standard setter”. But what protection does being a standard setter afford EU farmers if standards in relation to food safety, animal welfare and climate change are not applied equally to international trade?

An uneven playing field means farmers can neither compete on international markets nor against imports in the domestic market. The EU tillage sector is a case in point, where GM technologies are banned and yet imported product using these technologies determine the market price returned to farmers.

International trade is no longer being developed through rules-based bilateral or multilateral agreements. The preferred option now is to use trade wars and punitive tariffs against trade rivals to get what is desired.

In this environment, the financial impact of these tariffs carries more weight than the alignment of standards when trying to reach a trading agreement.

Given the global political landscape and the move towards populist national agendas, it is a trend that is unlikely to change. It is also a trend that will go unchallenged while the WTO’s appellate body (its appeals mechanism) remains shut down. The undermining of the WTO by China and the retaliatory action by the Trump administration to pull down the appellate body has neutered the WTO’s ability to police global trade.

It is this lawless global trading landscape that has seen the EU discharge its tough-talking trade commissioner in a bid to protect Europe’s economic interests. But while Hogan’s approach is getting traction, talking will only go so far. The most immediate indication as to whether the EU is prepared to back it up with tough actions will be the extent to which it rewards Donald Trump’s policy of trade wars and ripping up the Paris climate agreement by conceding on EU standards to reach a “mini deal”.

The second test will be the EU’s financial support for CAP. Slashing supports to “standard-setting” farmers faced with the headwinds of a global market where rules no longer apply and standards appear to be a tradeable commodity is at odds with the commissioner’s hard-hitting narrative. Reducing farmer support by €54bn hardly constitutes “playing to our strengths” or “improving our defence”. Nor would continuing with a Mercosur deal where the rules of trade are clearly being ignored.

Perhaps it is time Hogan started playing a bit of ground hurling back in Brussels to ensure policy direction is aligned to his tough talking.

Coronavirus: working together in uncertain times

In this week’s edition, we look at plans being put in place across the industry to try to minimise the impact of COVID-19. Should the infection spread to the extent that some are forecasting, the challenge will be availability of labour to operate processing facilities and maintain supply chains.

It is encouraging not only to see that contingency planning is well advanced but also the level of collaboration taking place across the industry to limit disruption. It is important that the necessary regulatory scope, outside of food safety, is provided to allow business the flexibility to adjust to this evolving situation.

At this stage, the impact on demand and market prices is largely unknown but it is unlikely to be positive. In the same way as Government has rightly announced a necessary package of reforms for sick pay, illness benefit and supplementary benefit, it must also stand ready to support farm incomes should the need arise.

The option of introducing an aid to private storage scheme or programmes that remove product should the supply chains be disrupted should be under consideration. While hopefully neither will be required, advance planning should still be taking place in the background. In line with concessions granted to the Italian government, any emergency measures should be allowed operate outside of Brussels’ fiscal and state-aid rules.

Meanwhile, our specialist team outline practical steps that farmers can take to ensure disruption to the farm is minimised in the period ahead and – most importantly – the steps to reduce the risk of the infection to family members.

Coronavirus: managing risk

We are assured that the coronavirus is spread person-to-person and is not a food-borne illness. By far the biggest risk to the meat and milk processing sectors is the threat of the virus affecting staff and subsequently the ability of milk processors to make cheese, powder or carry out simple tasks like basic pasteurisation or collection of milk.

Processors are working hard behind the scenes. Staff that can do multiple tasks may need to be called into other parts of the business. Is there a need to create a national processing team? By this I mean a team of individuals with the necessary experience and flexibility that could travel at short notice to a processor who finds out that 20, 30 or 40% of their processing team are out of action.

This may mean processors have to leave aside any differences so that a certain level of specialised personnel cover is created for what has been deemed a State-critical industry.

Appointment: Declan Marren joins our livestock team

We are delighted to welcome Dr Declan Marren on to our livestock team. Declan joined the Irish Farmers Journal in 2017 and has led our Farm Profitability Programme in Scotland since then. Back in Ireland, Declan will lead our Thrive programme, which aims to identify best practice technologies in dairy calf-to-beef systems.

He will oversee the management of our dairy beef demonstration farm in Cashel, Co Tipperary, and work closely with our demonstration farmers around the country.

Declan, who hails from a suckler and sheep farm in Co Sligo, holds a PhD from Teagasc Grange on beef production systems.

Tillage: crux time for cereal seed supply

Pressures on the requirement for certified spring barley seed could cause significant problems if we do not get a mix of crops planted this spring.

The ongoing bad weather that has prevented normal planting patterns will lead to an inevitable scarcity of certified seed of spring barley is this becomes the default crop when planting gets underway. Growers are advised to secure seed and also be aware of the need to get other crops like spring wheat and beans planted to ease the pressure. This scarcity is exacerbated due to the bad weather experienced across much of northern Europe which prevented winter crop planting.

SHARING OPTIONS