Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by a virus called bovine herpes virus-1 (BoHV-1).

IBR has worldwide distribution with the exception of a limited number of countries which have successfully eradicated it.

In addition to the impact on health and productivity, it also affects the trade of animals, semen and embryos.

In Ireland, IBR is mostly involved in respiratory infections, being one of the viral agents involved in the bovine respiratory disease (BRD) complex.

Infection with this virus is widespread, with an estimated 75% to 80% of both beef and dairy Irish herds containing animals that have been infected.

How to recognise IBR

Cattle with IBR typically have a watery discharge from the nose and eyes and may present with red nose and eyes. In severe cases, ulcers develop on the muzzle and lining of the nasal passages, which as they heal can develop scabs.

These changes extend into the windpipe, leading to coughing and noisy breathing if severe enough.

Affected animals may be dull, off their feed and have a high temperature (41.7-42.50C/107-1080F). Laboratory testing is required to make a definite diagnosis.

The severity of the clinical signs is influenced by a number of factors, including the husbandry system, secondary infections, degree of stress and age.

Disease is typically milder in dairy herds and more severe in beef units in the absence of immunity. Bacterial infections of the airways and lungs alongside IBR also results in more severe disease.

While most affected cattle will recover, a low percentage will die. Although infection is relatively uncommon in very young calves, infection may spread beyond the airways to the gut (producing scour), brain (producing nervous signs) and other internal organs and, as a result, death rates in this age group are often higher than in older cattle.

Infection with BoHV-1 has also been associated with abortions, although available evidence from the regional veterinary laboratories (RVLs) suggests that this is a sporadic event in Ireland.

How does the virus spread between animals and herds?

The virus is mainly spread directly by close contact between animals.

The nasal discharge from infected animals can contain very high levels of virus and as a result infection can spread rapidly through a herd when susceptible cattle come in contact with infectious cattle or items contaminated by them, such as feeders and drinkers.

It can also be shed from the reproductive tract, including semen, resulting in venereal transmission.

Airborne spread may also occur over distances of up to 5m. Indirect transmission within or between herds can also occur through movement or sharing of contaminated facilities, equipment or personnel.

Latently infected carriers

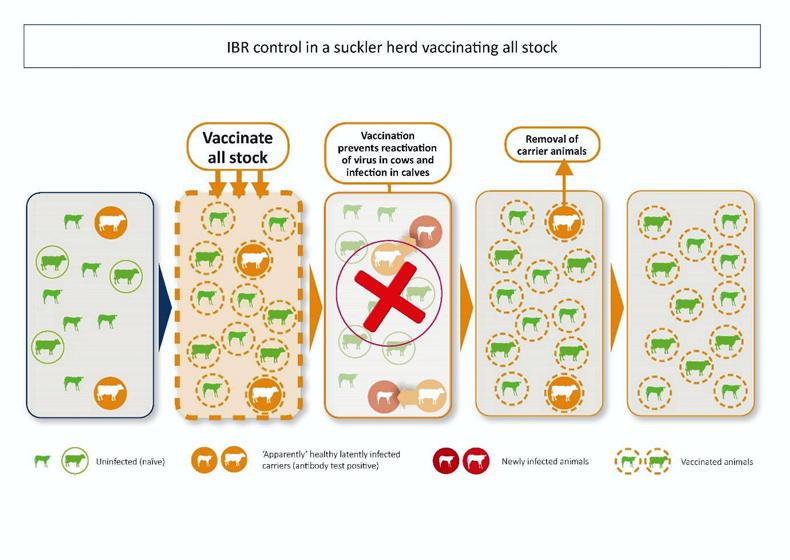

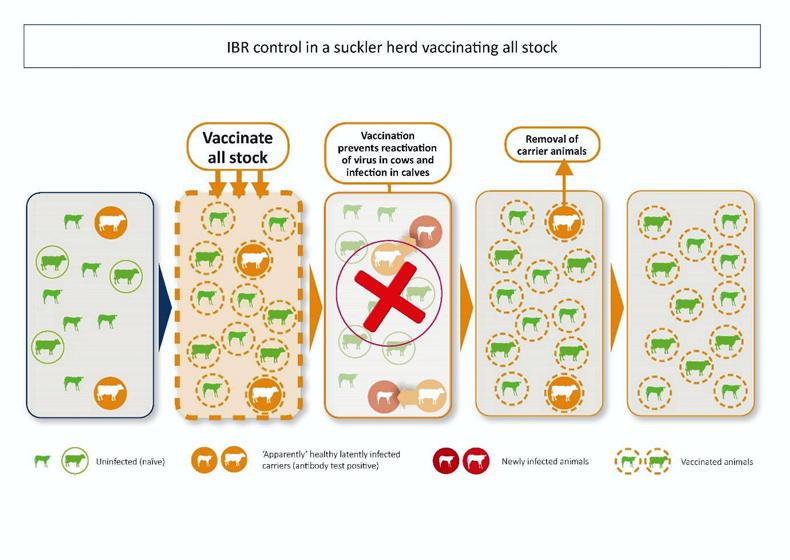

Animals that recover from infection will develop antibodies but this does not eliminate the virus. Instead, the virus establishes lifelong latent infection in the nerve cells within the animal’s brain. Carrier animals do not shed the virus but stress (transport, calving, etc) can trigger its reactivation, which leads to new infection in other susceptible cattle.

In breeding herds, this can result in transmission of the virus from cows to calves. In drystock units, it can result in outbreaks where animals are brought together, often from different sources, with some being carriers and others susceptible to infection.

These latently infected carriers play a central role in maintaining IBR in infected herds, where they act as a reservoir of infection.

They will typically remain antibody positive for life.

How to treat IBR

As with other viral infections there is no specific treatment for IBR. Secondary bacterial infections can be managed with antibiotics and animals with elevated temperature treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories.

Preventative vaccination of the remaining animals in the herd can help to minimise disease spread in an outbreak and vaccination of the infected animal will reduce the chances of virus reactivation.

Vaccines

There are several IBR vaccines containing either live or inactivated virus licensed for use in Ireland, all of them ‘marker’ gE-deleted vaccines.

This means that, when used with an appropriate test, it is possible to distinguish between animals positive due to vaccination and animals positive due to having been infected with IBR.

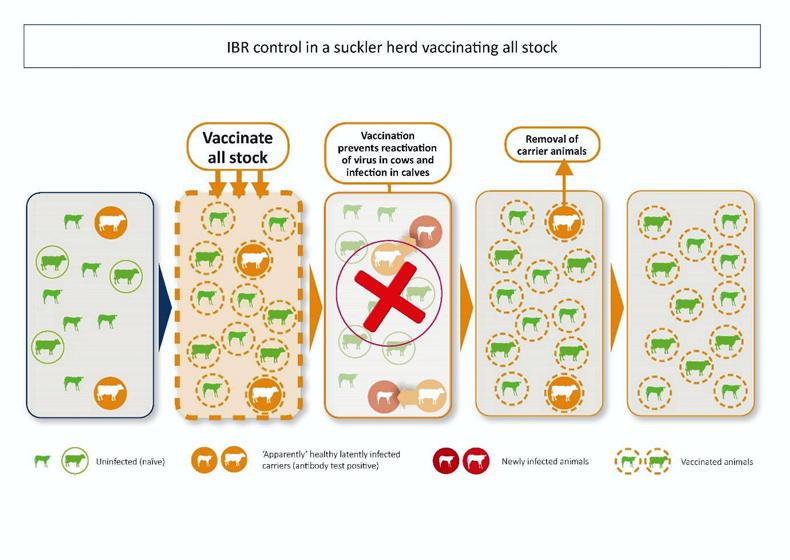

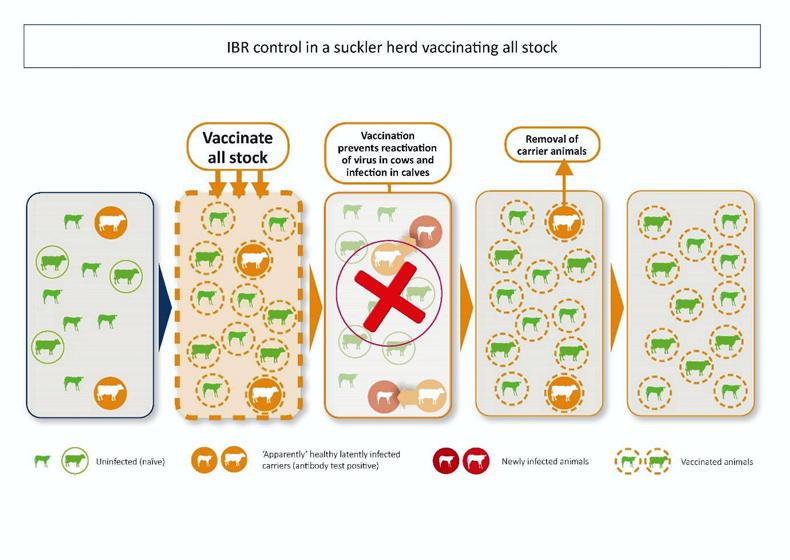

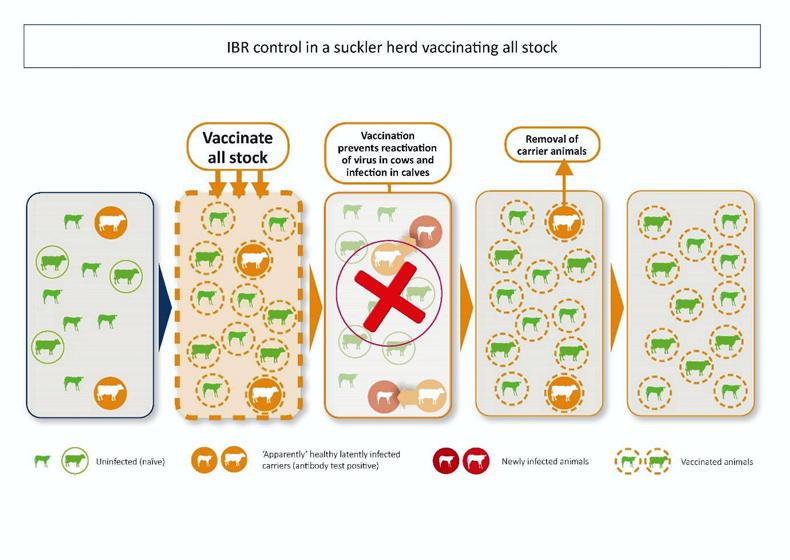

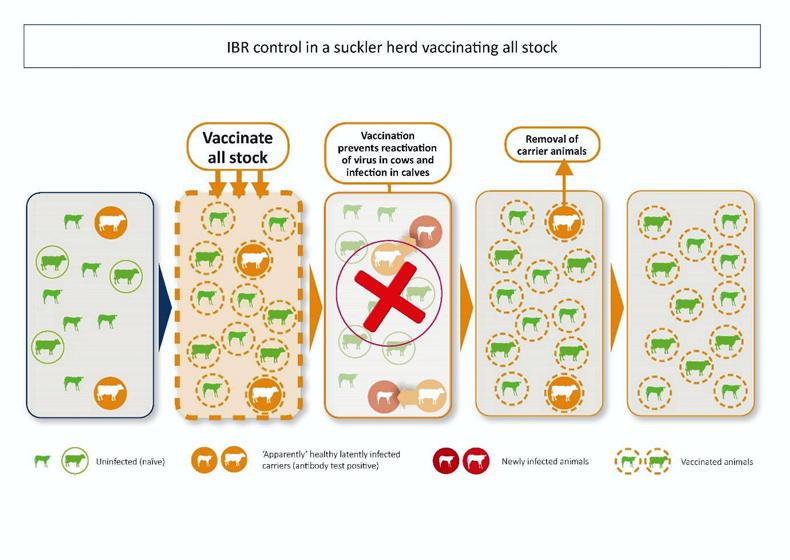

IBR vaccines are very good at preventing clinical signs and reducing the amount of virus shed following infection and reactivation, but they do not prevent field viruses from causing a limited infection.

Vaccination makes it less likely that a latent carrier will reactivate and shed the virus, and less likely that a previously uninfected (naïve) animal will become ill and spread the virus after exposure.

Since animals remain infected for life, older animals in a herd are more likely to be latently infected.

Therefore, if we want to prevent those animals being the source of infection for other, typically younger stock in the herd, we must include them in our vaccination plan.

Whole herd (including all breeding animals) and regular vaccination (according to manufacturers’ recommendations and with the herd’s veterinary practitioner’s advice), will lead to a decrease in the percentage of infected cattle in a herd over a period of time as older, positive cattle are displaced by younger, uninfected stock.

This way, we reduce the risk of re-activation of the virus by positive, typically older cattle.

IBR.

Decisions on which product and vaccination strategy to use in a particular situation should be made in consultation with your veterinary practitioner.

It is important to always read the datasheet provided with the vaccine to make sure that it is stored and used correctly, including being given by the correct route (which may be up the nose, into the muscle or under the skin).

How do you prevent IBR getting into your herd?

Closed herds have the lowest risk of introducing IBR but if you have to bring animals into your herd (including animals returning from shows or the mart), isolate for four weeks and test for antibodies before they join the herd.

Avoiding mixing home stock with cattle from other farms at pasture, housing or during contract rearing will help prevent accidental introduction of infection.

The benefits of control include improved herd health and production

As the virus is also capable to be transmitted indirectly through equipment and people, it is important to maintain good hygiene of shared equipment and facilities, using separate clothing or ensuring appropriate cleaning and disinfection of boots and clothing.

Good building design, ventilation, stocking density, ensuring good nutrition and low stress environments are key.

IBR.

Purchasing for

store, finishing or export markets

IBR is a recognised part of the respiratory disease complex in herds where animals are purchased from multiple sources and mixed after purchase.

Transport and mixing can result in outbreaks of IBR following reactivation of latent infection and spread to susceptible animals. Vaccination, (ideally in advance of movement or on arrival on farm), along with measures to reduce stress during transport and following arrival, can help control these outbreaks.

What happens if I have

IBR in my herd?

Herd infections with IBR can be clinical (where animals are obviously sick), sub-clinical (where no animals are obviously sick) or a mixture of both.

Various factors including the immune status of the herd, the management (degree of contact between animal groups, stress levels, etc) of the herd, and the strain of the virus will determine what type of herd infection is present.

In the absence of control, IBR usually remains in a herd for a very long time once it is introduced because all infected animals become ‘latent carriers’ for life.

Herds with medium to high levels of infection should consider introducing whole herd vaccination.

The benefits of control include improved herd health and production, the ability to sell animals into semen collection centres and the ability to export live cattle to countries that are IBR-free (or which have recognised control programmes).

Herds with a low prevalence of infection or that are negative for IBR should review their biosecurity to minimise the risk of introducing the disease and consider introducing/extending/maintaining vaccination as agreed with their vet to the whole herd to reduce the impact from a reintroduction of the virus.

Vaccination will not always be required.

Herds that breed bulls for AI

Animals that have antibodies to IBR (even if as a result of vaccination) are legally prohibited from entering semen collection centres. These herds are recommended to have eradication programmes in place (if not already IBR-free).

Potential AI sires should not be included in vaccination programmes and where these are in place, careful planning to prevent accidental exposure to vaccine virus is required.

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by a virus called bovine herpes virus-1 (BoHV-1).

IBR has worldwide distribution with the exception of a limited number of countries which have successfully eradicated it.

In addition to the impact on health and productivity, it also affects the trade of animals, semen and embryos.

In Ireland, IBR is mostly involved in respiratory infections, being one of the viral agents involved in the bovine respiratory disease (BRD) complex.

Infection with this virus is widespread, with an estimated 75% to 80% of both beef and dairy Irish herds containing animals that have been infected.

How to recognise IBR

Cattle with IBR typically have a watery discharge from the nose and eyes and may present with red nose and eyes. In severe cases, ulcers develop on the muzzle and lining of the nasal passages, which as they heal can develop scabs.

These changes extend into the windpipe, leading to coughing and noisy breathing if severe enough.

Affected animals may be dull, off their feed and have a high temperature (41.7-42.50C/107-1080F). Laboratory testing is required to make a definite diagnosis.

The severity of the clinical signs is influenced by a number of factors, including the husbandry system, secondary infections, degree of stress and age.

Disease is typically milder in dairy herds and more severe in beef units in the absence of immunity. Bacterial infections of the airways and lungs alongside IBR also results in more severe disease.

While most affected cattle will recover, a low percentage will die. Although infection is relatively uncommon in very young calves, infection may spread beyond the airways to the gut (producing scour), brain (producing nervous signs) and other internal organs and, as a result, death rates in this age group are often higher than in older cattle.

Infection with BoHV-1 has also been associated with abortions, although available evidence from the regional veterinary laboratories (RVLs) suggests that this is a sporadic event in Ireland.

How does the virus spread between animals and herds?

The virus is mainly spread directly by close contact between animals.

The nasal discharge from infected animals can contain very high levels of virus and as a result infection can spread rapidly through a herd when susceptible cattle come in contact with infectious cattle or items contaminated by them, such as feeders and drinkers.

It can also be shed from the reproductive tract, including semen, resulting in venereal transmission.

Airborne spread may also occur over distances of up to 5m. Indirect transmission within or between herds can also occur through movement or sharing of contaminated facilities, equipment or personnel.

Latently infected carriers

Animals that recover from infection will develop antibodies but this does not eliminate the virus. Instead, the virus establishes lifelong latent infection in the nerve cells within the animal’s brain. Carrier animals do not shed the virus but stress (transport, calving, etc) can trigger its reactivation, which leads to new infection in other susceptible cattle.

In breeding herds, this can result in transmission of the virus from cows to calves. In drystock units, it can result in outbreaks where animals are brought together, often from different sources, with some being carriers and others susceptible to infection.

These latently infected carriers play a central role in maintaining IBR in infected herds, where they act as a reservoir of infection.

They will typically remain antibody positive for life.

How to treat IBR

As with other viral infections there is no specific treatment for IBR. Secondary bacterial infections can be managed with antibiotics and animals with elevated temperature treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories.

Preventative vaccination of the remaining animals in the herd can help to minimise disease spread in an outbreak and vaccination of the infected animal will reduce the chances of virus reactivation.

Vaccines

There are several IBR vaccines containing either live or inactivated virus licensed for use in Ireland, all of them ‘marker’ gE-deleted vaccines.

This means that, when used with an appropriate test, it is possible to distinguish between animals positive due to vaccination and animals positive due to having been infected with IBR.

IBR vaccines are very good at preventing clinical signs and reducing the amount of virus shed following infection and reactivation, but they do not prevent field viruses from causing a limited infection.

Vaccination makes it less likely that a latent carrier will reactivate and shed the virus, and less likely that a previously uninfected (naïve) animal will become ill and spread the virus after exposure.

Since animals remain infected for life, older animals in a herd are more likely to be latently infected.

Therefore, if we want to prevent those animals being the source of infection for other, typically younger stock in the herd, we must include them in our vaccination plan.

Whole herd (including all breeding animals) and regular vaccination (according to manufacturers’ recommendations and with the herd’s veterinary practitioner’s advice), will lead to a decrease in the percentage of infected cattle in a herd over a period of time as older, positive cattle are displaced by younger, uninfected stock.

This way, we reduce the risk of re-activation of the virus by positive, typically older cattle.

IBR.

Decisions on which product and vaccination strategy to use in a particular situation should be made in consultation with your veterinary practitioner.

It is important to always read the datasheet provided with the vaccine to make sure that it is stored and used correctly, including being given by the correct route (which may be up the nose, into the muscle or under the skin).

How do you prevent IBR getting into your herd?

Closed herds have the lowest risk of introducing IBR but if you have to bring animals into your herd (including animals returning from shows or the mart), isolate for four weeks and test for antibodies before they join the herd.

Avoiding mixing home stock with cattle from other farms at pasture, housing or during contract rearing will help prevent accidental introduction of infection.

The benefits of control include improved herd health and production

As the virus is also capable to be transmitted indirectly through equipment and people, it is important to maintain good hygiene of shared equipment and facilities, using separate clothing or ensuring appropriate cleaning and disinfection of boots and clothing.

Good building design, ventilation, stocking density, ensuring good nutrition and low stress environments are key.

IBR.

Purchasing for

store, finishing or export markets

IBR is a recognised part of the respiratory disease complex in herds where animals are purchased from multiple sources and mixed after purchase.

Transport and mixing can result in outbreaks of IBR following reactivation of latent infection and spread to susceptible animals. Vaccination, (ideally in advance of movement or on arrival on farm), along with measures to reduce stress during transport and following arrival, can help control these outbreaks.

What happens if I have

IBR in my herd?

Herd infections with IBR can be clinical (where animals are obviously sick), sub-clinical (where no animals are obviously sick) or a mixture of both.

Various factors including the immune status of the herd, the management (degree of contact between animal groups, stress levels, etc) of the herd, and the strain of the virus will determine what type of herd infection is present.

In the absence of control, IBR usually remains in a herd for a very long time once it is introduced because all infected animals become ‘latent carriers’ for life.

Herds with medium to high levels of infection should consider introducing whole herd vaccination.

The benefits of control include improved herd health and production, the ability to sell animals into semen collection centres and the ability to export live cattle to countries that are IBR-free (or which have recognised control programmes).

Herds with a low prevalence of infection or that are negative for IBR should review their biosecurity to minimise the risk of introducing the disease and consider introducing/extending/maintaining vaccination as agreed with their vet to the whole herd to reduce the impact from a reintroduction of the virus.

Vaccination will not always be required.

Herds that breed bulls for AI

Animals that have antibodies to IBR (even if as a result of vaccination) are legally prohibited from entering semen collection centres. These herds are recommended to have eradication programmes in place (if not already IBR-free).

Potential AI sires should not be included in vaccination programmes and where these are in place, careful planning to prevent accidental exposure to vaccine virus is required.

SHARING OPTIONS