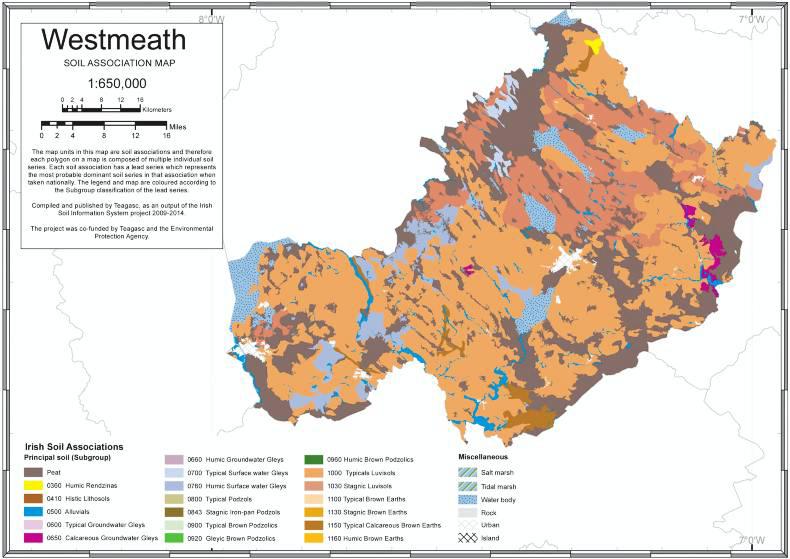

Co Westmeath is famous for its rivers and lakes and is widely known as The Lakeland of Ireland. The county forms part of the midlands and largely consists of undulating topography, with a general absence of mountainous areas. The landscape is made up of rolling lowlands, with soil parent material consisting nearly exclusively of limestone bedrock giving rise predominantly to luvisols (clay movement down the soil profile).

The calcium-rich bedrock found here directly influences certain aspects of farming that are quite specific to this area. Notably, there are several stud farms in the county where mares are put into foal in spring to take advantage of the calcium-rich plains that are considered to contribute to foal bone development.

Overall, agriculture in Co Westmeath includes a mix of tillage, sheep, cattle and dairy farming. The area around Moate is a well-known cattle-rearing area. Dairy farming is expected to increase in the future.

Two-thirds of the soils in Co Westmeath are luvisols, which are soils where clay material from the topsoil has moved down the profile and been deposited further down in the subsoil. These are very good agricultural soils and due to their higher clay content, retain nutrients well.

However, the increase in clay in the subsoil can slow down the movement of water through the soil. As a result, they can be moderately to imperfectly drained, depending on the overall texture of the soil.

The most commonly found are the ‘Elton’ series (found in associations 1000a and 1000c led by subgroup 1000). These soils have good moisture-holding capacity, are very productive and have a wide use range including grazing and tillage. While these are good soils, they can have weak structure and could be prone to compaction or poaching if stocked during wetter periods.

Stagnic luvisols are the next most commonly found soil type in Westmeath. In addition to the properties of luvisols, these soils also highlight indicators of stagnic features.

Most obvious will be the presence of mottled colouring, which occurs when the soil has been wet for long enough periods that oxygen moves too slowly to aerate the soil. This results in naturally red colours turning into grey/blue colours.

Surface-water gleys are found on the landscape too, especially in western parts of the county, along the Longford border. Essentially, these are poorly draining soils that occur due to a slowly permeable subsurface layer that slows movement of water through the soil profile.

This layer is typically due to either a higher clay content or dense material in the subsoil. This results in seasonal waterlogging for prolonged periods of the year.

The surface-water gleys here are humic and are all ‘Howardstown’ series (found in association 0760c led by subgroup 0760). The soils of this series are derived from medium to moderately fine-textured calcareous glacial till. The use-range of these soils is limited due to the weak structure, slow permeability and poor drainage, but good management can facilitate optimum production.

Co Westmeath is famous for its rivers and lakes and is widely known as The Lakeland of Ireland. The county forms part of the midlands and largely consists of undulating topography, with a general absence of mountainous areas. The landscape is made up of rolling lowlands, with soil parent material consisting nearly exclusively of limestone bedrock giving rise predominantly to luvisols (clay movement down the soil profile).

The calcium-rich bedrock found here directly influences certain aspects of farming that are quite specific to this area. Notably, there are several stud farms in the county where mares are put into foal in spring to take advantage of the calcium-rich plains that are considered to contribute to foal bone development.

Overall, agriculture in Co Westmeath includes a mix of tillage, sheep, cattle and dairy farming. The area around Moate is a well-known cattle-rearing area. Dairy farming is expected to increase in the future.

Two-thirds of the soils in Co Westmeath are luvisols, which are soils where clay material from the topsoil has moved down the profile and been deposited further down in the subsoil. These are very good agricultural soils and due to their higher clay content, retain nutrients well.

However, the increase in clay in the subsoil can slow down the movement of water through the soil. As a result, they can be moderately to imperfectly drained, depending on the overall texture of the soil.

The most commonly found are the ‘Elton’ series (found in associations 1000a and 1000c led by subgroup 1000). These soils have good moisture-holding capacity, are very productive and have a wide use range including grazing and tillage. While these are good soils, they can have weak structure and could be prone to compaction or poaching if stocked during wetter periods.

Stagnic luvisols are the next most commonly found soil type in Westmeath. In addition to the properties of luvisols, these soils also highlight indicators of stagnic features.

Most obvious will be the presence of mottled colouring, which occurs when the soil has been wet for long enough periods that oxygen moves too slowly to aerate the soil. This results in naturally red colours turning into grey/blue colours.

Surface-water gleys are found on the landscape too, especially in western parts of the county, along the Longford border. Essentially, these are poorly draining soils that occur due to a slowly permeable subsurface layer that slows movement of water through the soil profile.

This layer is typically due to either a higher clay content or dense material in the subsoil. This results in seasonal waterlogging for prolonged periods of the year.

The surface-water gleys here are humic and are all ‘Howardstown’ series (found in association 0760c led by subgroup 0760). The soils of this series are derived from medium to moderately fine-textured calcareous glacial till. The use-range of these soils is limited due to the weak structure, slow permeability and poor drainage, but good management can facilitate optimum production.

SHARING OPTIONS