In theory, all capital investments in a farm business should lead to extra profits on the farm. However, past experience has shown that poorly planned capital investments tie up valuable cash in the business which can adversely affect profitability.

With the opening of the TAMS II scheme in late 2015 and further tranches in 2016, on-farm capital investment has become very attractive for all farmers despite the short-term profit outlook across all sectors.

While it is important to make the most of TAMS II grant opportunities as they arise, it is essential that all farmers plan any farm investment very carefully. A number of areas should be examined from a financial perspective.

Should you make the investment?

We believe that farmers need to justify all capital expenditure. Capital investments tie up valuable working capital (cash) on a farm. Therefore, all farmers need to examine the need and return of any capital investment. With the short-term outlook for farming looking poor in 2016 and cashflow within most family farm businesses coming under pressure, all capital expenditure needs to be reviewed on the basis of its return on profitably to the farm.

Standard practice in other types of business entities is for a capital investment to be made based on its rate of return. Rate of return is a simple calculation based on the additional profit (less interest) an investment will make as a percentage of the cost of that investment. For example, the building of a milking parlour for €100,000 will allow you milk more and increase farm profits by €9,000. This would equate to a return on investment of 9% per year. This rate needs to be compared with the cost of borrowing or the cost of using your own funds (don’t forget your own funds if left on deposit would have accumulated interest). Therefore, the investment needs to earn enough additional profits to justify it.

Investors in other types of business would expect a return on their investment of somewhere between 7% and 10%. In most family farm businesses, due to the short-term outlook on profitability, there is very limited potential for a capital gain. Therefore, should any farmer make a capital investment in 2016?

With the short term outlook for farming looking poor, farmers should look for a return on investment of at least 5% per year. After all, one of the main objectives of a farmer must be to make a profit, and spending valuable funds on an investment that does not increase profits on the farm in the medium or long term has to be seriously reviewed.

Cashflow pressures

The next step for the farmer is deciding how they are going to finance the expenditure or development. Although the farm might need the development, and you have established that the investment will increase profitability, the farmer must now establish the best way to pay for the investment and at the same time minimise the impact on cash-flow. The most common mistakes farmers make when financially planning an investment are as follows:

1. Underestimating the total time and cost of an investment – Not accounting for a contingency fund.

2. Funding investment directly out of cashflow.

3. Not reviewing their borrowing capacity for a bank loan accurately.

a. Borrowing short-term.

b. Not correctly structuring loan.

Cashflow implications

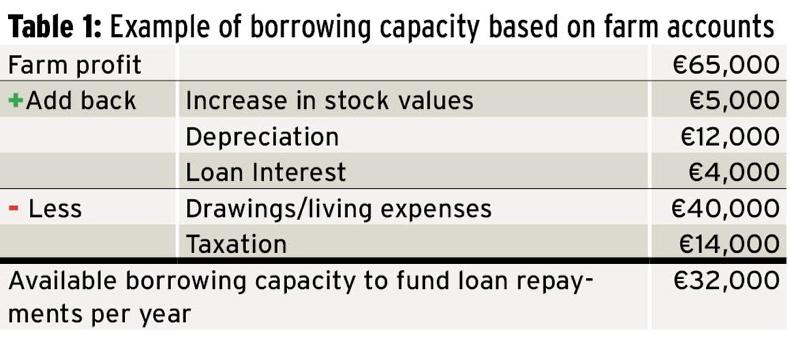

Once the cost of the development has been established (including contingency), the next step is securing funding. Most farm investments are funded out of either existing funds (savings) or loans and often a combination of both. If a farmer is planning to borrow the money, there will be a period between paying for the development and receiving grant and VAT 58 refund. If borrowing from a bank, this portion of the loan is called “bridging”. The remainder of the investment should then go on a term loan. The two main banks are currently offering loans for capital investments at about 4.5% to 5% interest. While the bank will calculate a repayment capacity when a farmer applies for a loan, the individual farmer should also calculate their own borrowing capacity. Borrowing capacity varies across every individual farm. In essence, borrowing capacity is established by calculating the cash funds available to pay a loan after farm has discounted the cost of living, tax and other capital investments in a given year from the farm profit. Table 1 outlines the borrowing capacity of a farm with a farm profit of €65,000.

Borrowing capacity should be calculated over a three year average and stress tested to allow for possible interest increase etc.

With farmers in expansion phases, the repayment capacity is sometimes not enough. However, these farmers secure the loan through detailed projections, eg increasing herd size by 20% will increase profits and therefore create the required repayment capacity. When relying on potential future increased profits to secure a loan, it is vital that a farmer’s projections are accurate.

Loan structures

Farmers tend to underestimate the costs associated with an investment. They further compound this by either borrowing short-term and/or funding some of the development out of cashflow. At the very minimum a capital investment should be borrowed at the rate of the capital allowances, eight years if not over a 10- to 15-year period. Spreading the loan out over a longer period reduces the impact on cash in any given year in making repayments. In low-margin years such as 2016 this can make a huge difference. Structuring loans to suit your farming enterprise will also help cashflow on a farm.

If a farmer is partly or fully funding a development through existing funds and cashflow, they must avoid creating hardcore debt. This is where a farmer uses working capital to fund development and creates a scenario where his creditors and overdraft drastically increase. This can cause huge issues on a farmer’s ability to effectively run their farm day-to-day. Merchant credit and overdraft rates are among the highest form of credit.

TAX planning issues

You must consider the following taxes when planning capital expenditure on buildings:

1. Value-added tax (VAT).

2. Income tax.

3. Capital repayment trap.

Vat-registered farmers

If you are a VAT-registered farmer you can reclaim any VAT payable by you on capital work in the normal way on your VAT return, which will either reduce the VAT you owe for that period or entitle you to a refund for the period.

Recommendations

Claim the VAT as it is being invoiced to you rather than waiting for the job to be finished. This will help your cashflow and also avoid delays arising from Revenue queries that commonly arise if a relatively large claim is made. Remember, it is the invoice date that determines the VAT taxable period in which a refund can be claimed, not the date you pay the building contractor/supplier.

VAT-unregistered farmers

Unlike VAT-registered farmers, VAT-unregistered farmers are restricted in the items on which they can reclaim the VAT suffered on building works. VAT-unregistered farmers are entitled to reclaim VAT incurred on building and land improvements and also on certain items of fixed plant such as bulk tanks, milking facilities, etc, subject to a time limit of four years. If the asset is disposed of or ceases to be used in the farming business within one year, the VAT reclaimed and interest must be repaid to Revenue.

Recommendations

A. You are required to submit invoices in support of the claim. It is important to ensure your building contractor/supplier, when invoicing you, uses the same name as is on your VAT registration. For instance, if the VAT registration is in the name of “Joe Blogs Farm Partnership” and the contractor makes out the invoice to “Joe Blogs” only, Revenue will refuse to sanction the refund of the VAT suffered on that invoice.

B. Moveable plant placed in the building will not qualify for a VAT refund to a VAT unregistered farmer. When projecting your costs and financial requirements for the project, sit down with your accountant to quantify the amount of VAT reclaimable and allow adequate time in your cashflow projection for the project for receipt of the refund.

Tax write-off

The tax write-off period for farm buildings and land improvements is seven years (15% + 10% in year seven). Items of plant and machinery such as the milking parlour can be written off against tax at 12.5% per year, ie it will take eight years to get the full tax write-off on plant and machinery.

The three year tax write-off period for pollution control expenditure ran out on 31 December 2010 and pollution control work carried out after that date attracts the normal seven-year write-off period.

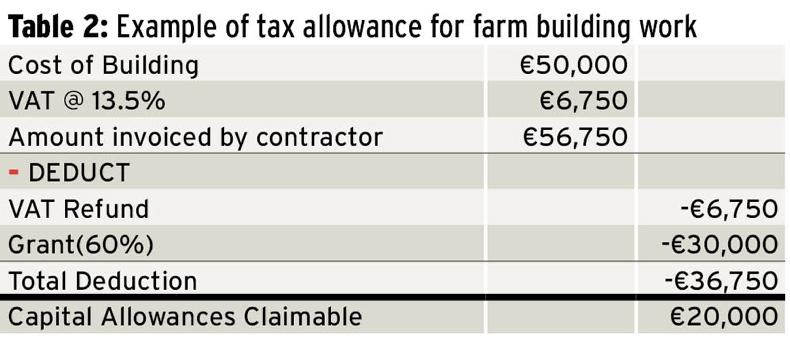

The annual tax allowance is calculated as a percentage of the gross cost minus VAT refundable and the grant. Table 2 shows an example of tax allowances claimable for a €50,000 building project.

This will be claimed as follows: €3,000 for the first six years and €2,000 in year seven. The value of these allowances by way of actual tax saved depends on the marginal tax rate of the individual farmer.

The capital repayment trap

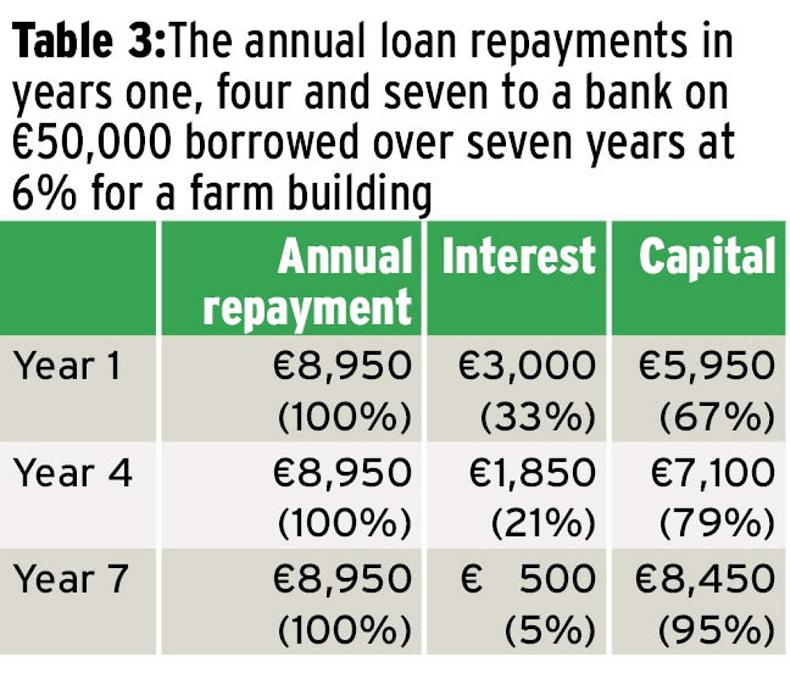

The profits shown on a farm profit and loss account only shows bank interest payable but not the capital repayment element of loan repayments. The capital repayment element has to be funded from after tax income. Table 3 outlines the annual loan repayments in years one, four and seven to a bank on €50,000 borrowed over seven years at 6%.

From this example, you can see that the tax deductible interest element of the repayment in year one of €3,000 is 33% of the total amount repayable, which drops to €500, being 5% of the total annual payment in year seven. A farmer taxable at 50% tax rate (including levies, PRSI, USC) would have to earn €16,900 profit before tax in year seven to repay the €8,450 capital element to the bank. It is therefore vital to understand the difference between the yearly profit as shown on a profit and loss account and the actual surplus cash that is needed to be generated in order to meet the capital element of loan repayments.

To read the full Buildings and TAMS II Focus supplement, click here.

SHARING OPTIONS