Many farmers who closed up paddocks in good time last autumn are in a good position with a favourable supply of grass. This is putting farmers who generally lamb outdoors in a great position after a few difficult years and possibly enticing those who generally lamb indoors or ceased the practice in recent years to reconsider outdoor lambing.

The main attraction is lower labour and feed costs but this statement should be taken with an air of caution. Outdoor lambing also requires high levels of management and, similar to indoor lambing, its success is highly dependent on advance preparations. Research carried out by AFBI a few years ago highlighted a number of factors that should be taken into account.

Value of grass

Good quality grass (grown from tightly grazed paddocks) is potentially five to 10 units higher in nutritive value than high-quality grass silage with a nutritive value listed as similar to a high-energy 18% protein ewe concentrate. As well as being potentially 30% cheaper than grass silage, the fact that ewes will consume up to 50% more dry matter compared with grass silage makes grass the ideal feed to meet the elevated nutritional demands of single- and twin-bearing ewes in late pregnancy without the need for concentrate supplementation.

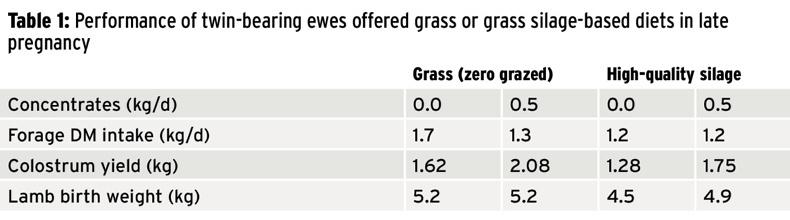

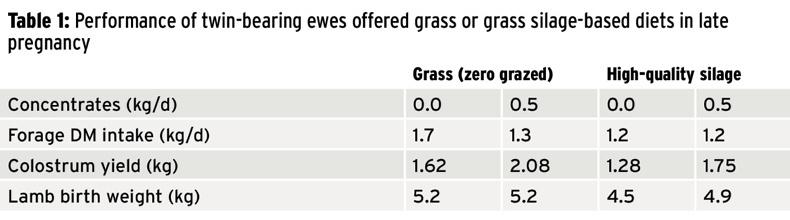

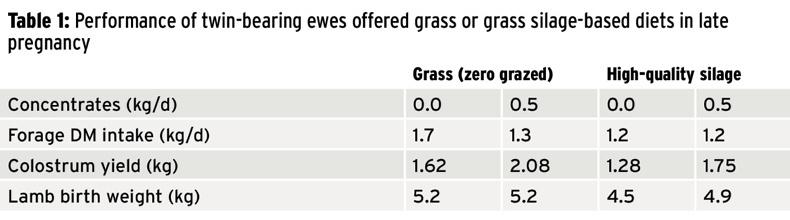

This is reflected in Table 1 which shows the performance of twin-bearing ewes fed a diet of grass or grass silage in late pregnancy. The ewes on the grass diet gave rise to heavier lambs than the ewes on the high-quality grass silage and concentrate diet, while producing a slightly lower colostrum yield but still sufficient to meet the demand of suckling lambs.

Surplus grass

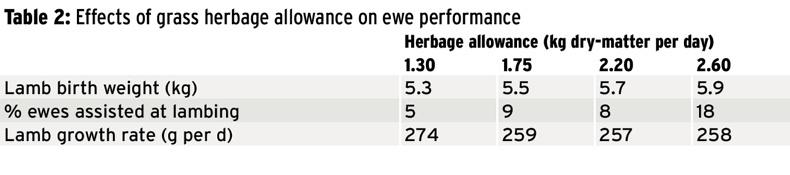

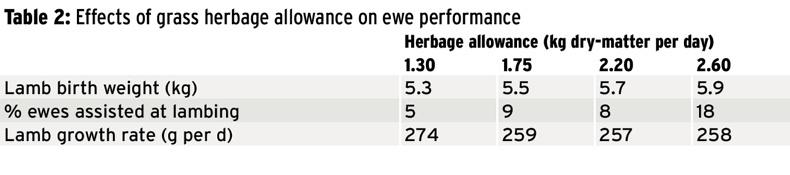

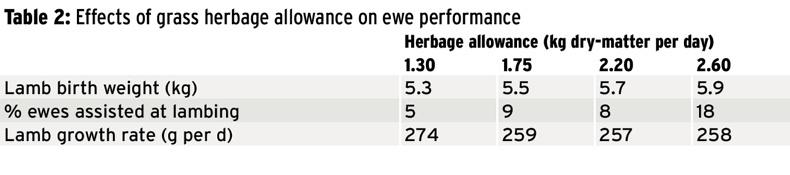

It may seem strange to be saying after the recent difficult spring seasons, but strong grass supplies also bring risks in the form of ewes consuming too much grass. This gives rise to the birth of oversized lambs, lambing difficulty and higher levels of labour and mortality. This is reflected in Table 2, which shows the effect of increasing the volume of grass on offer to ewes on lamb birth weight, assistance required and subsequent performance. When ewes were offered high volumes of grass, the number of ewes requiring assistance spiked to 18% as a result of heavier lambs and ewes in excessive body condition at lambing.

As such, it is crucial that grass intake is controlled. It is unlikely in most flocks that sufficient grass will be available to lamb all animals outdoors. Therefore, the best approach is to focus on offering grass to the ewes that will benefit most. These include twin- and triplet-bearing ewes and particularly those that may be below optimum body condition as these will benefit most from the nutritional boost.

Most farmers practising outdoor lambing successfully retain single- and triplet-bearing ewes indoors to better supervise triplet-bearing ewes, restrict intake in single-bearing ewes and give the best opportunity to cross foster. Twin-bearing ewes are also housed until two to three weeks pre-lambing or supplemented outdoors in a confined area to help conserve and build grass supplies.

Stocking rate

The general stocking rate recommended is about five ewes per acre for a mid-March lambing flock that has sufficient grass reserves available or coming on stream to carry ewes post lambing. This is also a vital aspect to consider as there is little point in lambing outdoors if it reduces labour, but then requires supplementation in early lactation. This recommendation is based on a grass height of about 5cm and may need to be increased if heavier covers are present. Aim to target surplus grass to ewes that deliver the best return.

Weather and levels of grass utilisation will also have a role to play. Irrespective of the system, ewe body condition should be monitored regularly and only suitable sheep should be selected.

Other key factors

There are a number of other important factors that should be taken into account if considering outdoor lambing:

Ewe breed: hill breeds such as Scottish Blackface, Cheviot and Swaledale and crosses such as the Mule, Greyface and Hiltex or Lleyn breed are most suited due to their natural maternal instincts.

Facilities available: while outdoor lambing has the potential to lower labour, it will not eliminate supervision or handling of some animals. A handling pen or shed should be available to flock sheep while backup facilities are advised to guard against inclement weather.

Grass supplies: do not leave yourself short of grass. Spreading 20 to 25 units of nitrogen when ground conditions allow will help boost supplies.

Mismothering: sufficient grass supplies are essential in avoiding supplementation and, in turn, lambs getting mis-mothered by their dams. It is also important to either remove ewes and lambs from the group or ewes still to lamb regularly to cut down on the number of lambs in close quarters with ewes still to lamb and the possibility of mismothering. Most farmers leave freshly lambed ewes for 12 to 24 hours to develop a bond before moving.

Sheltered paddocks: settled weather will greatly influence mortality and the risk can be minimised by selecting sheltered paddocks. Special thanks to Ronald Annett who worked at AFBI at the time this research was collated and provided to us.

Read more

Special focus: lambing 2017

Many farmers who closed up paddocks in good time last autumn are in a good position with a favourable supply of grass. This is putting farmers who generally lamb outdoors in a great position after a few difficult years and possibly enticing those who generally lamb indoors or ceased the practice in recent years to reconsider outdoor lambing.

The main attraction is lower labour and feed costs but this statement should be taken with an air of caution. Outdoor lambing also requires high levels of management and, similar to indoor lambing, its success is highly dependent on advance preparations. Research carried out by AFBI a few years ago highlighted a number of factors that should be taken into account.

Value of grass

Good quality grass (grown from tightly grazed paddocks) is potentially five to 10 units higher in nutritive value than high-quality grass silage with a nutritive value listed as similar to a high-energy 18% protein ewe concentrate. As well as being potentially 30% cheaper than grass silage, the fact that ewes will consume up to 50% more dry matter compared with grass silage makes grass the ideal feed to meet the elevated nutritional demands of single- and twin-bearing ewes in late pregnancy without the need for concentrate supplementation.

This is reflected in Table 1 which shows the performance of twin-bearing ewes fed a diet of grass or grass silage in late pregnancy. The ewes on the grass diet gave rise to heavier lambs than the ewes on the high-quality grass silage and concentrate diet, while producing a slightly lower colostrum yield but still sufficient to meet the demand of suckling lambs.

Surplus grass

It may seem strange to be saying after the recent difficult spring seasons, but strong grass supplies also bring risks in the form of ewes consuming too much grass. This gives rise to the birth of oversized lambs, lambing difficulty and higher levels of labour and mortality. This is reflected in Table 2, which shows the effect of increasing the volume of grass on offer to ewes on lamb birth weight, assistance required and subsequent performance. When ewes were offered high volumes of grass, the number of ewes requiring assistance spiked to 18% as a result of heavier lambs and ewes in excessive body condition at lambing.

As such, it is crucial that grass intake is controlled. It is unlikely in most flocks that sufficient grass will be available to lamb all animals outdoors. Therefore, the best approach is to focus on offering grass to the ewes that will benefit most. These include twin- and triplet-bearing ewes and particularly those that may be below optimum body condition as these will benefit most from the nutritional boost.

Most farmers practising outdoor lambing successfully retain single- and triplet-bearing ewes indoors to better supervise triplet-bearing ewes, restrict intake in single-bearing ewes and give the best opportunity to cross foster. Twin-bearing ewes are also housed until two to three weeks pre-lambing or supplemented outdoors in a confined area to help conserve and build grass supplies.

Stocking rate

The general stocking rate recommended is about five ewes per acre for a mid-March lambing flock that has sufficient grass reserves available or coming on stream to carry ewes post lambing. This is also a vital aspect to consider as there is little point in lambing outdoors if it reduces labour, but then requires supplementation in early lactation. This recommendation is based on a grass height of about 5cm and may need to be increased if heavier covers are present. Aim to target surplus grass to ewes that deliver the best return.

Weather and levels of grass utilisation will also have a role to play. Irrespective of the system, ewe body condition should be monitored regularly and only suitable sheep should be selected.

Other key factors

There are a number of other important factors that should be taken into account if considering outdoor lambing:

Ewe breed: hill breeds such as Scottish Blackface, Cheviot and Swaledale and crosses such as the Mule, Greyface and Hiltex or Lleyn breed are most suited due to their natural maternal instincts.

Facilities available: while outdoor lambing has the potential to lower labour, it will not eliminate supervision or handling of some animals. A handling pen or shed should be available to flock sheep while backup facilities are advised to guard against inclement weather.

Grass supplies: do not leave yourself short of grass. Spreading 20 to 25 units of nitrogen when ground conditions allow will help boost supplies.

Mismothering: sufficient grass supplies are essential in avoiding supplementation and, in turn, lambs getting mis-mothered by their dams. It is also important to either remove ewes and lambs from the group or ewes still to lamb regularly to cut down on the number of lambs in close quarters with ewes still to lamb and the possibility of mismothering. Most farmers leave freshly lambed ewes for 12 to 24 hours to develop a bond before moving.

Sheltered paddocks: settled weather will greatly influence mortality and the risk can be minimised by selecting sheltered paddocks. Special thanks to Ronald Annett who worked at AFBI at the time this research was collated and provided to us.

Read more

Special focus: lambing 2017

SHARING OPTIONS