The principles of ventilation are simple. In an enclosed space, airborne substances accumulate – they cannot get out. Facilitating an airflow through this enclosed space will act to displace these substances, replacing them with fresh air. Many pneumonia-causing viruses and bacteria are airborne, and ensuring that airflow through a cattle shed is sufficient will help to move these substances, and other waste gases, away from the animals and reduce the burden on them. Unfortunately, lots of Irish cattle sheds were not designed with this in mind.

The principles of ventilation are simple. In an enclosed space, airborne substances accumulate – they cannot get out. Facilitating an airflow through this enclosed space will act to displace these substances, replacing them with fresh air.

Many pneumonia-causing viruses and bacteria are airborne, and ensuring that airflow through a cattle shed is sufficient will help to move these substances, and other waste gases, away from the animals and reduce the burden on them. Unfortunately, lots of Irish cattle sheds were not designed with this in mind.

The stack effect

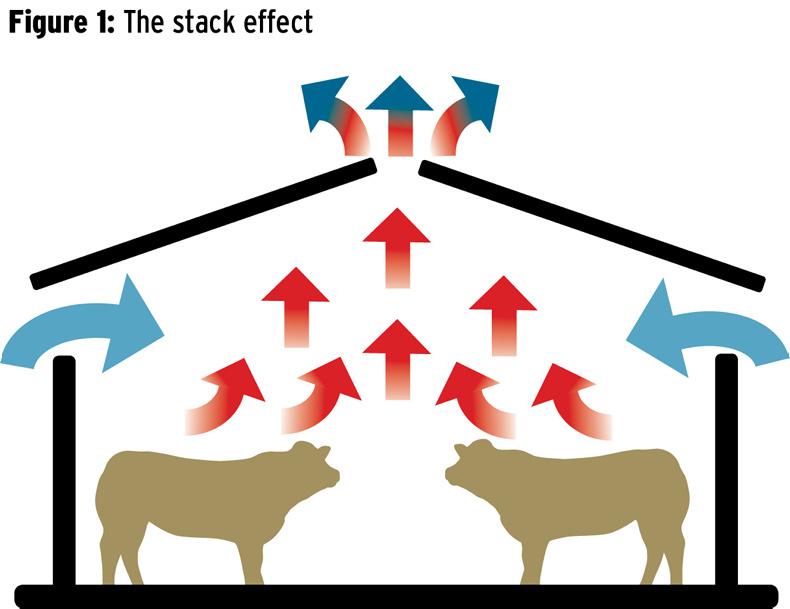

The fact that animals produce heat works to our advantage when trying to properly ventilate sheds. Heat rises and so the heat that our cattle produce in the shed pushes air upwards, towards the roof. This is where our air outlet comes into play – air should have a route to escape from the shed (outlet) at its highest point.

Where the outlet in a shed is insufficient to allow enough air out, stale air – often concentrated with waste gases and airborne bacteria and viruses – accumulates. In this situation, our animals are actively burdened with disease-causing agents and a stressor such as weaning, fighting, or a temperature change can weaken their immune systems and let these agents in.

In addition, airborne gases produced in animal excretions, as well as moisture, can themselves act as stress-inducers – they should be eliminated too. Think of the ammonia smell that greets you in certain sheds.

As this air leaves the shed, new air is naturally sucked in behind it to fill the void. This fresh air enters the shed via inlets in the side of the building, ideally just above animal level. The stack effect is illustrated in Figure 1.

The weather can be harnessed to help ventilate sheds, as well as the stack effect. By creating large outlets in the sides of buildings – opposite to the prevailing wind – we encourage air to flow through the upper airspace of the building also, enhancing the stack effect. In Ireland, wind ventilation is often the most common driver of air movement in livestock sheds.

Draughts

While airflow in a cattle shed is generally a good thing, it should be minimised at animal level. “Can you feel that draught?”How many times have you, or has someone in your company, asked that question? Humans are very sensitive to moving air and animals are no different.

Even air moving at a speed of 0.5m per second will result in young calves burning more energy to warm themselves, leaving less energy available in their systems for performance and, crucially, their immune systems. Draughts can be just as bad, if not worse, than poor air movement and stuffy conditions. Hence, there should be minimal airflow at animal level – from 0m to 2m. In draughty houses, calves will be seen to huddle along walls.

Inlet and outlet areas

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine has published a number of criteria regarding ventilation that must be met when erecting buildings (Figure 2).

Outlet ventilation must be provided along the full length of the roof apex; 450mm wide for a house up to 15m wide; 600mm wide for a house up to 24m wide; and 750mm wide for larger houses. A ridge cap over the outlet is not recommended, but when provided it must stand unobstructed and fully clear of the roof by 275mm, 350mm, or 425mm, respectively, for the three widths of houses noted above. Angled upstands placed on the roof on both sides of the ridge outlet improve the ventilation and prevent most rain access. They are a strongly recommended alternative to ridge capping.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Where spaced sheeting with a gap of at least 20mm is installed over the entire roof, a central ridge outlet, though recommended, is not mandatory.

According to the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, inlet ventilation must be provided directly under the eaves for the full length of each side of the house. An unobstructed depth of 450mm must be provided in houses up to 15m wide; 600mm deep in houses up to 24m wide and 750mm deep for larger houses. Alternatively, to reduce wind-speed and rain, options such as pre-painted steel sheets with ventilation slots (vented sheeting) over their surface can be used for inlet ventilation.

They must be positioned immediately below eaves for the full length of the house and have a minimum depth of 1.5m.

Signs of inadequate ventilation

Cobwebs.Ammonia smell.Nasal

discharge.Pneumonia outbreak.Damp

bedding.Coughing.Open-mouthed breathing by cattle.Condensation/rust damage on walls and roof.IMPROVING VENTILATION

Yorkshire boarding: staggered wood panelling. Vented sheets.Open doors and block initial 1.5m to 2m with bales.Spaced roof sheeting.Removing part of or complete solid side sheets.Knocking top block rows from the shed wall.Central ridge outlet.For years, Longford BETTER farmers Frank and Des Beirne persevered through winters in which multiple cases of viral pneumonia would rear their heads, despite the pair’s best efforts. Their slatted unit had an open front facing northeast and closed side-sheeting – air was hitting a dead end at the back of the shed. Expanding the building by a further two bays had minimal effect. Local vets McDonnell and Flynn were called out. They carried out a smoke test in the house. This involves sending coloured smoke into the atmosphere of a building to see how air behaves – such tests can be extremely useful. It revealed an inadequate rate of airflow in the building.

The Beirnes removed four bays-worth of closed sheeting. Initially, they replaced the sheeting with green netting and have since replaced three of the four bays with Yorkshire boarding (pictured).

“The air feels fresher and you can feel the air flow. It’s an ongoing process, but we’ve had no issues so far,” Des said.

Read more

Focus on winter indoor management

SHARING OPTIONS: