The central topography of Brazil is defined by a vast tropical savannah known as the Cerrado. With an intense drought period that lasts from March to September, the Cerrado savannah is an area of Brazil that does not easily lend itself to productive agriculture.

Soil fertility is amongst the poorest in the world, with many Brazilian farmers describing the Cerrado as “dead land”. To overcome the challenges of the Cerrado region, local farmers have turned to Embrapa, a Brazilian agricultural research body similar in many ways to Teagasc.

While run for profit, Embrapa is affiliated with the Brazilian ministry for agriculture and operates 46 research stations throughout Brazil. Each research centre focuses on the agricultural practices best suited to the region, particularly given the diversity of Brazil’s climate and topography from state to state.

At Embrapa’s research centre in the heart of the Cerrado, researchers are working on how to improve soil fertility in the region and intensify agricultural production.

From the mid-1990s, the Brazilian government, with the help of Embrapa, began incentivising farmers to reclaim the Cerrado land and make it fit for crop production through large-scale application of lime and gypsum (calcium sulphate). Under this incentive, Brazilian farmers ramped up lime application on land in the Cerrado to 16m tonnes by 1999. By 2005, this had increased further to 25m tonnes, or 5t/ha.

This intense focus on improving soil fertility led to substantial changes in the subsoil condition of the Cerrado red soil, which typically has a clay content of 60%. The subsoil changes allowed for better rooting of crops, which helped them better cope with the intense drought season.

After solving some of the region’s soil fertility challenges, Embrapa has since shifted its research focus to developing new systems of farming that could lend themselves to the Cerrado.

Integrated systems

One of the most eye-catching developments that illustrates the incredible potential of Brazil is the integrated system of livestock, cropping and forestry production.

For many years, Brazilian farmers have operated integrated livestock and cropping systems on their farms. However, the addition of forestry to this mix is a more recent development which is designed to reduce soil erosion.

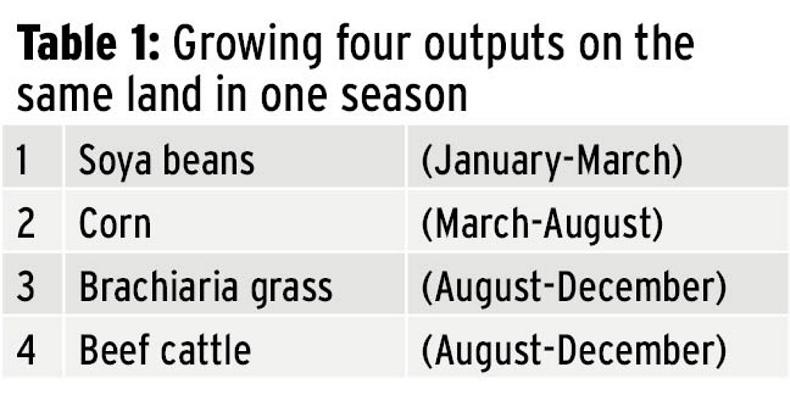

Embrapa has implemented this system in a section of the large-scale research farm it operates in the Cerrado. Researcher Roberto de Almeida walks us through the livestock, cropping and forestry demonstration, which he says allows a farmer to have four outputs from the land in a single year, along with a forestry crop every seven years.

The first step in this system is to plant symmetrical rows of eucalyptus trees at an extended distance. The area in between each row is where crops will be planted and its must be wide enough to allow modern equipment to pass through.

With the forest system laid out, the first crop to be planted is early-season soya bean that will be harvested in March. The soya bean harvest is usually followed with second season corn (maize), or safrinha corn, that will be harvested in July and August.

The safrinha corn is double-cropped with Brachiaria, which is a tough variety of grass native to the savannah that is roughly 50% digestible. This grass is then grazed for the remainder of the year by beef cattle, which also enjoy the shade provided by the eucalyptus trees.

Four outputs in one year

In this way, a farmer is getting four systems of production in a single year off the same land. After two or three years of the soya bean-corn rotation, the land will be left in grass for a number of years before the rotation restarts once more.

The eucalyptus trees will be ready to harvest seven years after planting, with the timber sold for use in construction or pulp. New lines of eucalyptus trees can be planted adjacent to the harvested tree stumps, which will degrade rapidly thanks to the heat in the soil.

While the Brazilian government is now incentivising this new system of farming, Roberto de Almeida says the take-up has been very low as many farmers are sceptical. The system is also restrictive due to the up-front costs.

Either way, Embrapa’s research centre in the Cerrado region highlights the incredible potential to produce in Brazil, where one farmer can harvest four crops off the same land in a single year.

SHARING OPTIONS