The introduction of the Microgeneration Support Scheme in December 2021, which finally paved the way for small-scale generators to sell renewable electricity back to the grid and receive payment, was hailed as a breakthrough moment for farmers.

The scheme aimed to simplify the process for farmers – and the public – to generate their own renewable electricity and get paid for exporting the surplus to the grid.

However, for a few pioneering renewable energy producers, this scheme, specifically the method used to determine the amount of exported electricity has cost them thousands.

Reuben Higgins and his wife Jackie, in partnership with their son Nicholas, run a drystock farm in West Sligo overlooking the Atlantic and are among those affected.

They have a strong passion for green energy, which was clear to see by the electric car and bike in their driveway, along with the solar water heaters installed on their roof. The Irish Farmers Journal recently visited them in Sligo to discuss their situation.

With Reuben’s experience in telecommunications, he recognised the importance of energy and started developing a renewable energy project on his farm 15 years ago.

As the electricity bills for his 200ac, 60-cow dairy farm continued to rise, he saw renewable electricity as a logical choice.

After considering various options such as hydro, he determined that wind power would be the most suitable technology, given his location on an exposed and windy site. With a NC6 three-phase electricity connection, his farm could accommodate an 11kW wind turbine.

Wind turbine

After two years of research, including installing an anemometer for 12 weeks where he found great wind speeds of 5.4 meters/second at 20m in height, he opted to install an Irish-built 11kW C&F turbine.

Manufactured in Galway, the turbine cost €45,400 including VAT, which he couldn’t claim back, and a further €4,000 for concrete, cabling, ducting etc.

He also now pays an average of €2,000/year on maintenance and servicing. Reuben did not receive any grant aid for this turbine and made the investment on a commercial basis.

The 11kW turbine cost over €50,000 to install.

He firmly believed that environmentally, this was the right choice for his farm.

At the time, about two-thirds of the electricity produced from the turbine was used on-site, which gave a payback period of around eight years.

Exporting

For the first 10 years of the turbine’s operation, Reuben was able to export surplus electricity to the grid through a Microgeneration Pilot Scheme with Electric Ireland. Electric Ireland is the retail division of the State-owned utility Electricity Supply Board (ESB).

During this period, he received a payment of 9c/kWh for each kilowatt of electricity exported to the grid. The payment was provided as a rebate on his electricity bill, typically amounting to around €1,800 a year.

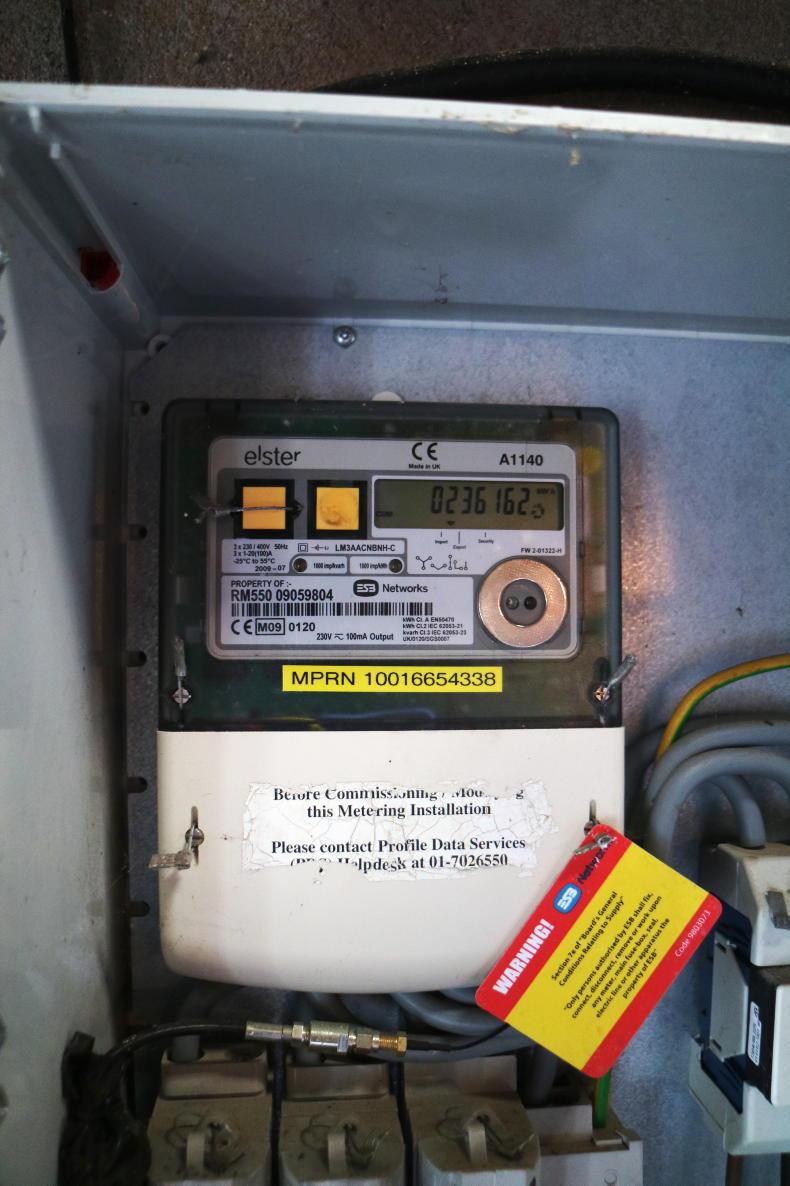

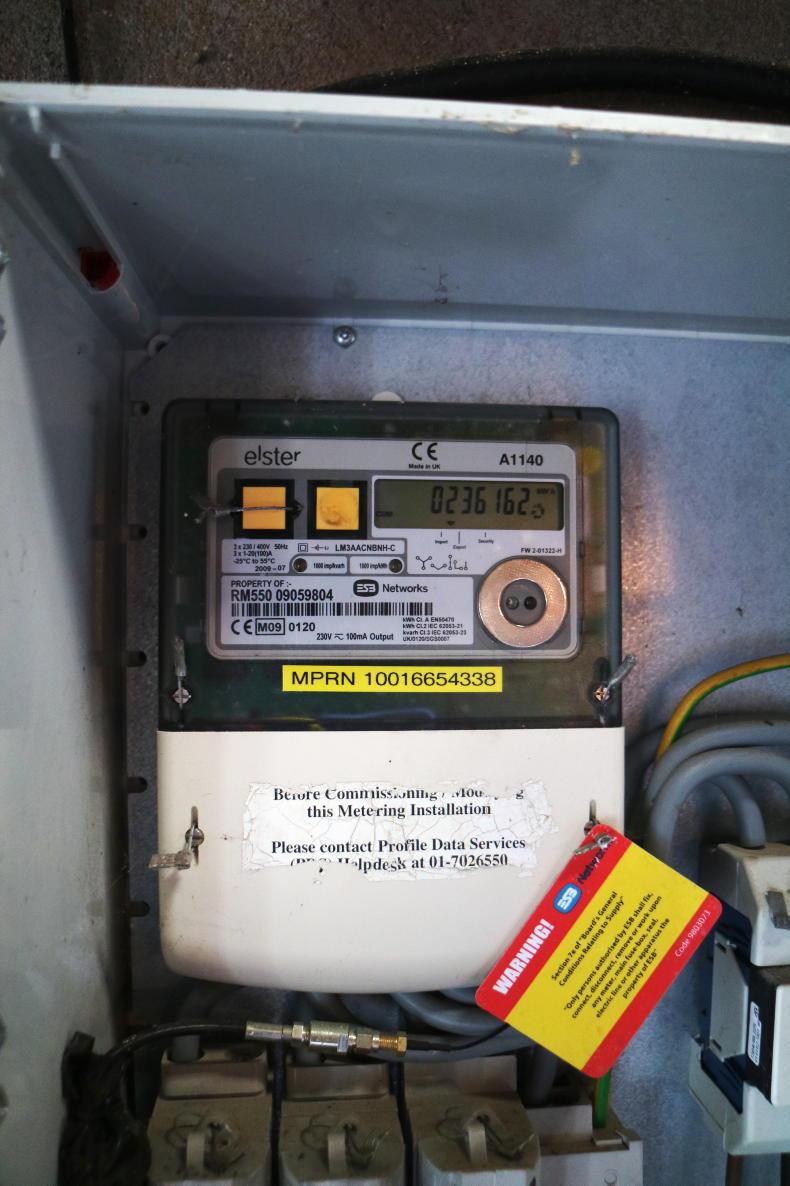

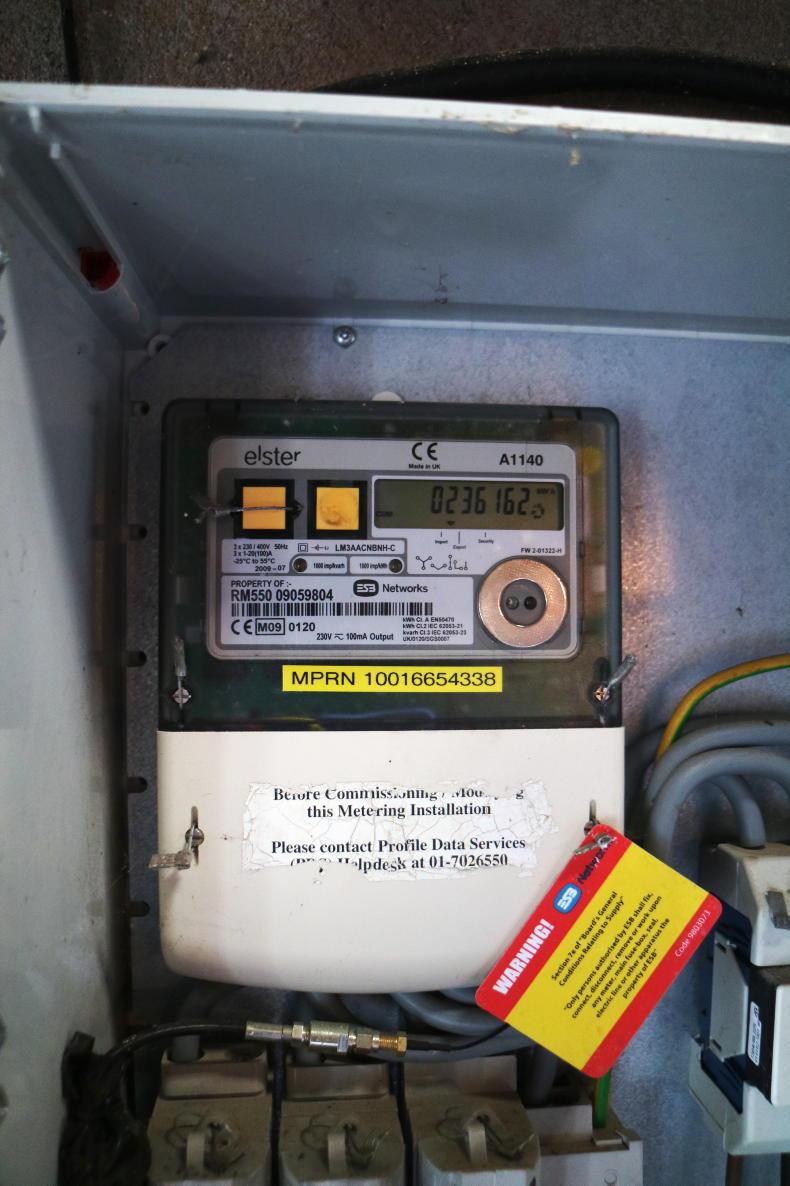

This was monitored using an import/export meter, which sent the readings to Electric Ireland, explains Reuben.

This simple digital meter showed all imported, produced, consumed and exported electricity on his farm.

Reuben meticulously took monthly readings of his meter himself, kept in a log in his office.

Short-changed

He stopped milking cows in 2019 and found himself in a position to export 60% of his electricity to the grid.

However, the pilot scheme ended in December 2021 and it would be 15 February 2022 before it was replaced by the newly launched Microgeneration Support Scheme (MSS), resulting in six weeks of no payment despite exporting to the grid as normal.

The MSS aimed to facilitate easy grid export by offering a competitive market rate for renewable electricity.

Electric Ireland’s new MSS rate was 21c/kWh, a significant increase from Reuben’s previous rate of 9c/kWh.

According to Reuben’s meter, he exported 19,788kWh of electricity from January to November 2022. At the new rate, this should have resulted in a rebate of over €4,000.

However, when he reviewed his bill, Electric Ireland stated that just 2,856kWh of electricity was exported from February to December 2022, amounting to a rebate of approx. €600.

Reuben meticulously took monthly readings of his meter himself, kept in a log in his office

From January to February 2023, Reuben exported 4,812kWh, which should have resulted in a rebate of around €1,010. However, according to Electric Ireland, he only exported 591kWh of electricity, giving a rebate of €124.

Realising that something was seriously wrong with the readings, Reuben contacted Electric Ireland, thinking it was a simple error.

Meter problems

In email correspondence, Electric Ireland informed Reuben that under the MSS, he needed a new smart meter to monitor units of energy exported to the grid, and they no longer accepted readings from old import/export meters.

The frustrating part for Reuben is that, after emailing ESB Networks, it appears they will not begin rolling out smart meters for three-phase connections until this autumn at the earliest.

Electric Ireland told Reuben that customers with an old import/export meter would receive an estimated credit based on a formula provided by the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) and calculated by ESB Networks.

Under the MSS, data from old import/export meters are no longer accepted.

The email stated: “Even though you have an import/export meter, your credit is still estimated until you receive a smart meter from ESB Networks.

“I understand that this may be frustrating for you, especially if you know that you exported more energy than the estimated credit you received. However, please note that we are following the guidelines set out by the Government for the Microgeneration Scheme,” it concluded.

Minister Ryan

He took this directly to Minister Eamon Ryan’s special adviser, Paul Kenny.

Acknowledging the significant difference between Reuben’s estimated and actual exported figures, Kenny wrote to ESB Networks to seek clarification on the issue and to see if it could be resolved.

In emails seen by the Irish Farmers Journal, Kenny explained to Reuben that there appeared to be an issue with one element of the CRU’s formula, specifically the capacity factor.

The capacity factor is the ratio of average electricity produced, to the theoretical maximum possible, if the installed capacity of the system was generating at a maximum for a full year.

Kenny said that the issue could be attributed to either the capacity factor calculation by ESB Networks or the rules governing the capacity factor calculation by CRU.

He suggested that Reuben should write to ESB Networks, outlining that they may have incorrectly calculated his exported kWh. If this doesn’t work, he advised filing a complaint directly with CRU.

Frustration

When I sat down with Reuben at his kitchen table, his frustration was obvious.

Both Electric Ireland and Minister Ryan’s special adviser admitted to the issues in calculating the payments for his exported electricity.

Drystock farmer Reuben Higgins.

Reuben finds this wholly unfair and believes other small-scale renewable generators are likely facing the same issue.

He feels robbed, as Electric Ireland is paying only a fraction of the actual price for his electricity.

He took a big financial risk because he thought developing a renewable energy project was the right thing to do for his farm, and he expects a fair price in return.

Reuben feels that microgeneration is not taken seriously unless it’s a large-scale renewable project and this ordeal has supported his case.

As long as this remains unresolved, it severely undermines the narrative that there are new farm opportunities in renewable energy.

As such, Reuben strongly advises caution when considering renewable energy projects.

He reached out to the Irish Farmers Journal for help to shed light on the issue, as he has received little practical help to date.

The introduction of the Microgeneration Support Scheme in December 2021, which finally paved the way for small-scale generators to sell renewable electricity back to the grid and receive payment, was hailed as a breakthrough moment for farmers.

The scheme aimed to simplify the process for farmers – and the public – to generate their own renewable electricity and get paid for exporting the surplus to the grid.

However, for a few pioneering renewable energy producers, this scheme, specifically the method used to determine the amount of exported electricity has cost them thousands.

Reuben Higgins and his wife Jackie, in partnership with their son Nicholas, run a drystock farm in West Sligo overlooking the Atlantic and are among those affected.

They have a strong passion for green energy, which was clear to see by the electric car and bike in their driveway, along with the solar water heaters installed on their roof. The Irish Farmers Journal recently visited them in Sligo to discuss their situation.

With Reuben’s experience in telecommunications, he recognised the importance of energy and started developing a renewable energy project on his farm 15 years ago.

As the electricity bills for his 200ac, 60-cow dairy farm continued to rise, he saw renewable electricity as a logical choice.

After considering various options such as hydro, he determined that wind power would be the most suitable technology, given his location on an exposed and windy site. With a NC6 three-phase electricity connection, his farm could accommodate an 11kW wind turbine.

Wind turbine

After two years of research, including installing an anemometer for 12 weeks where he found great wind speeds of 5.4 meters/second at 20m in height, he opted to install an Irish-built 11kW C&F turbine.

Manufactured in Galway, the turbine cost €45,400 including VAT, which he couldn’t claim back, and a further €4,000 for concrete, cabling, ducting etc.

He also now pays an average of €2,000/year on maintenance and servicing. Reuben did not receive any grant aid for this turbine and made the investment on a commercial basis.

The 11kW turbine cost over €50,000 to install.

He firmly believed that environmentally, this was the right choice for his farm.

At the time, about two-thirds of the electricity produced from the turbine was used on-site, which gave a payback period of around eight years.

Exporting

For the first 10 years of the turbine’s operation, Reuben was able to export surplus electricity to the grid through a Microgeneration Pilot Scheme with Electric Ireland. Electric Ireland is the retail division of the State-owned utility Electricity Supply Board (ESB).

During this period, he received a payment of 9c/kWh for each kilowatt of electricity exported to the grid. The payment was provided as a rebate on his electricity bill, typically amounting to around €1,800 a year.

This was monitored using an import/export meter, which sent the readings to Electric Ireland, explains Reuben.

This simple digital meter showed all imported, produced, consumed and exported electricity on his farm.

Reuben meticulously took monthly readings of his meter himself, kept in a log in his office.

Short-changed

He stopped milking cows in 2019 and found himself in a position to export 60% of his electricity to the grid.

However, the pilot scheme ended in December 2021 and it would be 15 February 2022 before it was replaced by the newly launched Microgeneration Support Scheme (MSS), resulting in six weeks of no payment despite exporting to the grid as normal.

The MSS aimed to facilitate easy grid export by offering a competitive market rate for renewable electricity.

Electric Ireland’s new MSS rate was 21c/kWh, a significant increase from Reuben’s previous rate of 9c/kWh.

According to Reuben’s meter, he exported 19,788kWh of electricity from January to November 2022. At the new rate, this should have resulted in a rebate of over €4,000.

However, when he reviewed his bill, Electric Ireland stated that just 2,856kWh of electricity was exported from February to December 2022, amounting to a rebate of approx. €600.

Reuben meticulously took monthly readings of his meter himself, kept in a log in his office

From January to February 2023, Reuben exported 4,812kWh, which should have resulted in a rebate of around €1,010. However, according to Electric Ireland, he only exported 591kWh of electricity, giving a rebate of €124.

Realising that something was seriously wrong with the readings, Reuben contacted Electric Ireland, thinking it was a simple error.

Meter problems

In email correspondence, Electric Ireland informed Reuben that under the MSS, he needed a new smart meter to monitor units of energy exported to the grid, and they no longer accepted readings from old import/export meters.

The frustrating part for Reuben is that, after emailing ESB Networks, it appears they will not begin rolling out smart meters for three-phase connections until this autumn at the earliest.

Electric Ireland told Reuben that customers with an old import/export meter would receive an estimated credit based on a formula provided by the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) and calculated by ESB Networks.

Under the MSS, data from old import/export meters are no longer accepted.

The email stated: “Even though you have an import/export meter, your credit is still estimated until you receive a smart meter from ESB Networks.

“I understand that this may be frustrating for you, especially if you know that you exported more energy than the estimated credit you received. However, please note that we are following the guidelines set out by the Government for the Microgeneration Scheme,” it concluded.

Minister Ryan

He took this directly to Minister Eamon Ryan’s special adviser, Paul Kenny.

Acknowledging the significant difference between Reuben’s estimated and actual exported figures, Kenny wrote to ESB Networks to seek clarification on the issue and to see if it could be resolved.

In emails seen by the Irish Farmers Journal, Kenny explained to Reuben that there appeared to be an issue with one element of the CRU’s formula, specifically the capacity factor.

The capacity factor is the ratio of average electricity produced, to the theoretical maximum possible, if the installed capacity of the system was generating at a maximum for a full year.

Kenny said that the issue could be attributed to either the capacity factor calculation by ESB Networks or the rules governing the capacity factor calculation by CRU.

He suggested that Reuben should write to ESB Networks, outlining that they may have incorrectly calculated his exported kWh. If this doesn’t work, he advised filing a complaint directly with CRU.

Frustration

When I sat down with Reuben at his kitchen table, his frustration was obvious.

Both Electric Ireland and Minister Ryan’s special adviser admitted to the issues in calculating the payments for his exported electricity.

Drystock farmer Reuben Higgins.

Reuben finds this wholly unfair and believes other small-scale renewable generators are likely facing the same issue.

He feels robbed, as Electric Ireland is paying only a fraction of the actual price for his electricity.

He took a big financial risk because he thought developing a renewable energy project was the right thing to do for his farm, and he expects a fair price in return.

Reuben feels that microgeneration is not taken seriously unless it’s a large-scale renewable project and this ordeal has supported his case.

As long as this remains unresolved, it severely undermines the narrative that there are new farm opportunities in renewable energy.

As such, Reuben strongly advises caution when considering renewable energy projects.

He reached out to the Irish Farmers Journal for help to shed light on the issue, as he has received little practical help to date.

SHARING OPTIONS