It is a busy time on farms for general maintenance. Draining, cleaning ditches, mowing verges and cutting hedges are all taking place across the country, aided by an incredible spell of dry weather.

While not every year, many farmers will at some stage need to dispose of green waste on their farms.

Agricultural green waste arises mostly from the maintenance and management of farm hedgerows and land maintenance activities and includes branches, trimmings, tree tops and bushes.

This material can be bulky and awkward to transport, so until recently, the most effective way to deal with green waste was to burn it. Burning green waste was permitted between September and November under a legal exemption, once the local authorities were notifed. However, the exemption to burn green waste on farms came to an end in 2023.

Burning green waste is no longer allowed.

Following the publication of a detailed report by the Irish Bioenergy Association, the Department of Agriculture now suggests the following ways of dealing with the material.

Prevention is better than cure

The report first states that farmers should try to minimise the amount of green waste they produce through regular hedgerow maintenance and land management.

Chipping the material is an option but comes at a cost.

This message is contrary to messages coming from previous Government members, which advocated for leaving hedgerows to grow. However, the report suggests that changing practices around hedgerow management could result in a greater volume of waste needing to be dealt with in the future.

Flailing

Flailing is seen as the most effective way to deal with green waste. Regularly flailed hedgerows are incorporated back into the hedgerow ecosystem. The flailed material is used by various microorganisms and broken down into useful organic material.

Heavier material can also be chipped.

The current practice is considered an excellent method of maintaining hedgerows without generating green waste that must otherwise be disposed of or managed by the farmer, the report states.

Habitat creation

For more bulky material, it is suggested that green waste can be stockpiled on the farm in designated locations, such as corners of fields, and allowed to decompose in situ over a long period. This green waste material will serve as a habitat for a multitude of microfauna, macrofauna and native flora, the report states.

Woodchip would be sent ot bioenergy.

However, it is acknowledged that this would result in particularly bulky piles that would take long periods to break down.

Animal bedding

Green waste material can be chipped and used as winter bedding for livestock. Overwintering pads for livestock could also be constructed using wood chip material, as outlined in the report. However, chipping comes at a cost, and the final product may contain thorns or other contaminants, which could make it unsuitable for bedding.

Biofuel

Large quantities of small-diameter branching material are sometimes produced. This material can be used as biofuel, with Bord na Móna’s Edenderry plant being the destination for much of it.

A number of forest contractors have invested in specialised woodchippers and are actively using them to process forestry by-product material into woodchip fuel.

Could green waste be used to make biochar?

If there is enough suitable material, this method of disposal can be advantageous, as at least the disposal cost will be covered.

On-farm energy

The report states that large woody material can be an useful and sustainable source of energy for heating domestic homes, a practice that should be encouraged. However, cutting the material into usable sizes requires effort.

In some cases, it may be possible to use this material in industrial boilers.

Biochar

Biochar is one of the recommended findings listed as an alternative use for woody biomass. Biochar is a recalcitrant form of carbon, created when biomass is thermally converted through the process of pyrolysis.

Thermal conversion differs from combustion in that the intended output is the production of co-products such as biochar, rather than the elimination of material through combustion.

Biochar can be made from a wide variety of biomass feedstocks, with woody biomass being one of the more common types used.

Once created, biochar can have a very high carbon content that persists in the environment for decades, if not centuries.

However, the challenge with using biochar as an option to manage green waste is that it is not currently a widespread practice.

While systems for producing small amounts of biochar on farms do exist, a large-scale market for biomass or biochar material has yet to be established.

Conclusion

Realistically, the most feasible option for farmers to dispose of large volumes of green waste is either to flail and mulch it or to hire a contractor to chip and remove the material. While some farmers may choose to pile the waste in a corner to create a habitat for wildlife, which is beneficial, suggesting this as a solution for large volumes of material is not realistic. Ultimately, with the burning ban set to remain in place, managing large volumes of green waste will only result in additional costs for farmers.

In short

It is a busy time on farms for general maintenance. Draining, cleaning ditches, mowing verges and cutting hedges are all taking place across the country, aided by an incredible spell of dry weather.

While not every year, many farmers will at some stage need to dispose of green waste on their farms.

Agricultural green waste arises mostly from the maintenance and management of farm hedgerows and land maintenance activities and includes branches, trimmings, tree tops and bushes.

This material can be bulky and awkward to transport, so until recently, the most effective way to deal with green waste was to burn it. Burning green waste was permitted between September and November under a legal exemption, once the local authorities were notifed. However, the exemption to burn green waste on farms came to an end in 2023.

Burning green waste is no longer allowed.

Following the publication of a detailed report by the Irish Bioenergy Association, the Department of Agriculture now suggests the following ways of dealing with the material.

Prevention is better than cure

The report first states that farmers should try to minimise the amount of green waste they produce through regular hedgerow maintenance and land management.

Chipping the material is an option but comes at a cost.

This message is contrary to messages coming from previous Government members, which advocated for leaving hedgerows to grow. However, the report suggests that changing practices around hedgerow management could result in a greater volume of waste needing to be dealt with in the future.

Flailing

Flailing is seen as the most effective way to deal with green waste. Regularly flailed hedgerows are incorporated back into the hedgerow ecosystem. The flailed material is used by various microorganisms and broken down into useful organic material.

Heavier material can also be chipped.

The current practice is considered an excellent method of maintaining hedgerows without generating green waste that must otherwise be disposed of or managed by the farmer, the report states.

Habitat creation

For more bulky material, it is suggested that green waste can be stockpiled on the farm in designated locations, such as corners of fields, and allowed to decompose in situ over a long period. This green waste material will serve as a habitat for a multitude of microfauna, macrofauna and native flora, the report states.

Woodchip would be sent ot bioenergy.

However, it is acknowledged that this would result in particularly bulky piles that would take long periods to break down.

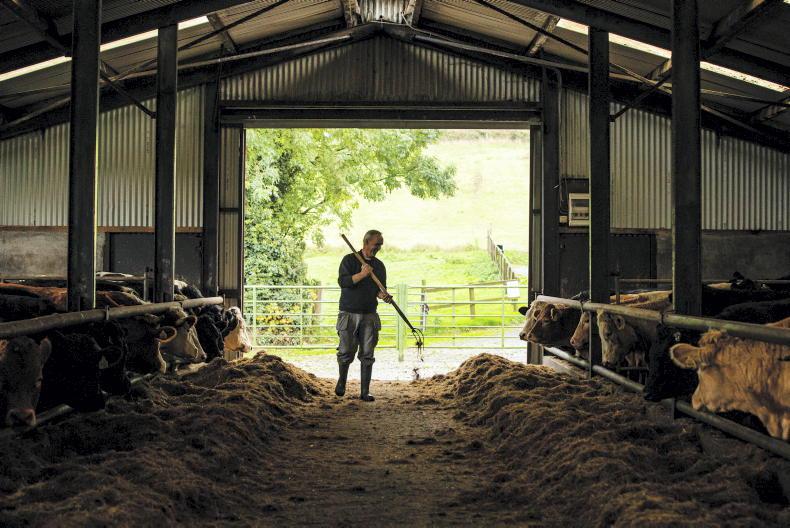

Animal bedding

Green waste material can be chipped and used as winter bedding for livestock. Overwintering pads for livestock could also be constructed using wood chip material, as outlined in the report. However, chipping comes at a cost, and the final product may contain thorns or other contaminants, which could make it unsuitable for bedding.

Biofuel

Large quantities of small-diameter branching material are sometimes produced. This material can be used as biofuel, with Bord na Móna’s Edenderry plant being the destination for much of it.

A number of forest contractors have invested in specialised woodchippers and are actively using them to process forestry by-product material into woodchip fuel.

Could green waste be used to make biochar?

If there is enough suitable material, this method of disposal can be advantageous, as at least the disposal cost will be covered.

On-farm energy

The report states that large woody material can be an useful and sustainable source of energy for heating domestic homes, a practice that should be encouraged. However, cutting the material into usable sizes requires effort.

In some cases, it may be possible to use this material in industrial boilers.

Biochar

Biochar is one of the recommended findings listed as an alternative use for woody biomass. Biochar is a recalcitrant form of carbon, created when biomass is thermally converted through the process of pyrolysis.

Thermal conversion differs from combustion in that the intended output is the production of co-products such as biochar, rather than the elimination of material through combustion.

Biochar can be made from a wide variety of biomass feedstocks, with woody biomass being one of the more common types used.

Once created, biochar can have a very high carbon content that persists in the environment for decades, if not centuries.

However, the challenge with using biochar as an option to manage green waste is that it is not currently a widespread practice.

While systems for producing small amounts of biochar on farms do exist, a large-scale market for biomass or biochar material has yet to be established.

Conclusion

Realistically, the most feasible option for farmers to dispose of large volumes of green waste is either to flail and mulch it or to hire a contractor to chip and remove the material. While some farmers may choose to pile the waste in a corner to create a habitat for wildlife, which is beneficial, suggesting this as a solution for large volumes of material is not realistic. Ultimately, with the burning ban set to remain in place, managing large volumes of green waste will only result in additional costs for farmers.

In short

SHARING OPTIONS