The Dublin Lockout of 1913 was arguably the most disruptive event of the 1913-23 period from a livestock exports perspective.

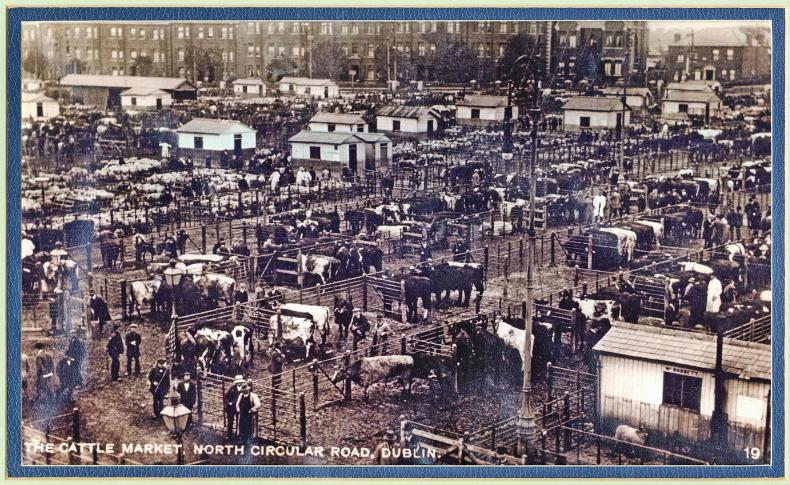

The Dublin Cattle Market and livestock shipping were early casualties of the Lockout.

The bitter industrial dispute crippled the city’s transport network from August 1913, while Dublin’s rail links to the rest of Ireland and ferry connections to Britain were seriously disrupted by late autumn as matters escalated and over 20,000 workers were locked out by their employers.

The battle of wills between employers’ leader William Martin Murphy and Jim Larkin of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) had dire consequences for cattle exports out of Dublin port and, as a consequence, for the Dublin Cattle Market.

Although strike activity was not reported at the market itself, it was proving increasingly difficult to move livestock to and from Dublin as the dispute spread beyond the city’s tram workers.

Cattle numbers

By September 1913, cattle numbers at the Prussia Street sale had halved, with fewer than 2,400 animals on offer each week when there should have been up to 6,000 animals for the peak autumn sales.

The reluctance of English buyers to travel to the Dublin market – due to unrest in the city and fears that they might be unable to get cattle and sheep shipped – compounded the impact of the Lockout on the Prussia Street sales.

The business losses at the market due to the dispute were estimated at £50,000 per week during the autumn.

The situation deteriorated in November when workers closed Dublin’s docks in solidarity with their fellow union members who were locked out.

Small numbers of cattle were still being shipped from the city’s docks using ‘free labour’ or non-union workers from outside Dublin. For example, the SS Blackrock carried 700 cattle from Dublin to Birkenhead at the end of November.

But such sailings were the exception and increasing numbers of cattle and sheep were shipped from ports such as Drogheda and Waterford due to the Lockout. This exacerbated the impact on the Dublin market.

However, by early January, 1914 the strike had collapsed, as the city’s desperate workers were forced to concede defeat and return to work.

Operations at Dublin’s docks returned to normal within a fortnight, with three vessels from the Dublin Steampacket Company departing with livestock to Liverpool and Manchester on the evening of 16 January.

More ships were due to depart the city for Birkenhead, Holyhead and Glasgow the same evening.

The trade at Prussia Street bounced back from the disruption of the Lockout and the number of animals sold at the market had recovered by the end of the spring.

Victim

Unfortunately, the real cost of the Lockout was paid by the many workers and their families who were forced to leave Dublin in the wake of the dispute.

Some of the labour brought into the city to help break the strike also paid a heavy price.

Liverpool native Edward Farrell was one such victim of the Lockout. He was found floating in the Alexandra Basin in January 1914 at the stern of the Laird Line steamer the Lord Roberts.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: