The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently issued a report which gave nitrate concentrations in 20 Irish rivers a positive review, highlighting an improving (falling) trend in nitrate concentrations.

However, the document referenced catchments of concern, where nitrate concentrations need to be further reduced. The most downstream monitoring site on the rivers were used, giving a good indication of what is flowing into the estuary from the whole catchment.

Coastal and estuarine water is more impacted by nitrate than phosphorous, and these monitoring sites enable a calculation of the total amount (tonnes) of nitrogen entering the estuary from the catchment.

The term used to describe the amount of nitrogen (N) leaving a catchment is the ‘load’, which is calculated by multiplying the volume of water leaving the river (cubic meters) by the concentration (mg/l).

For example, 6,280t of nitrogen left the Slaney catchment in 2019. The Slaney estuary, from Enniscorthy to the mouth at Wexford Harbour, is receiving this load, and the concentration of nitrogen in the estuary is determined by how large a load is delivered.

Water quality

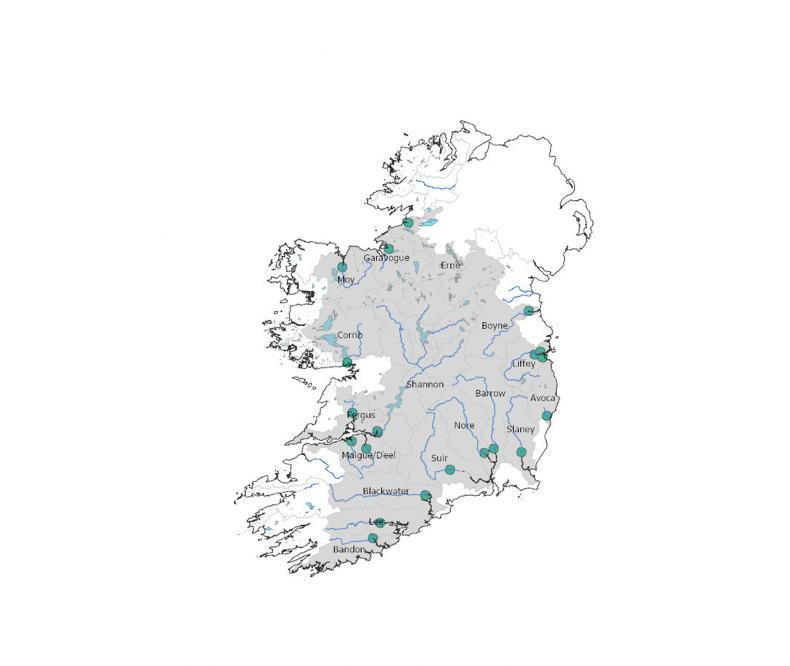

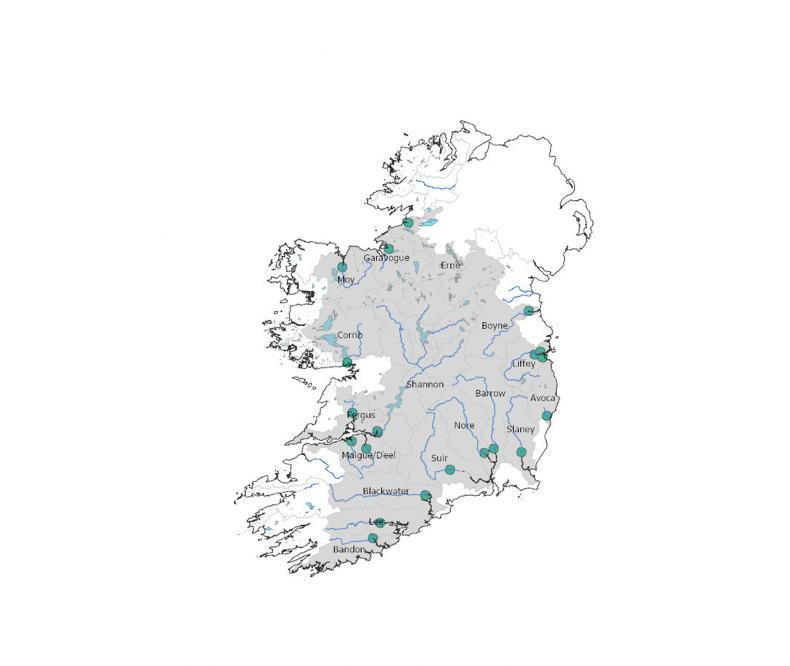

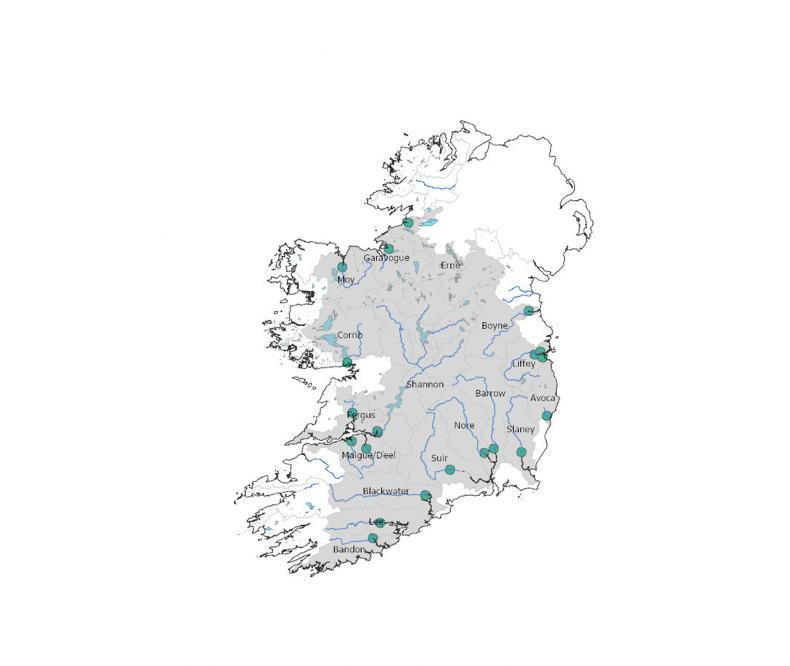

The green dots are nitrogen monitoring sites on Ireland's largest rivers. \ EPA

Ideally, for the estuary to have good ecological water quality, the average nitrogen concentration leaving the river as it enters the estuary should be below 2.6mg/l of N. (It is worth noting that the nitrate standard in water for human consumption is far less restrictive than the ecological limit – 11.3mg/l vs the 2.6mg N/l litre ecological standard).

Naturally, as a larger catchment drains a bigger area, you will have a greater volume and flow leaving, so it is easier to compare different catchments using the average nitrogen load for a given area, per hectare for example.

Many parts of this country typically get 1m of rainfall per year. Some 0.5m is taken up by growing plants through evapotranspiration, so the amount left flowing out our rivers is around 0.5m. This is called the “effective” rainfall. For half a meter of effective rainfall, a concentration of 2.6mg N/l is equivalent to 13kg N/ha.

While 13kg N/ha will possibly mean more to people than 2.6mg N/l, it is an average figure for the whole catchment.

There are always areas that are far riskier than others. Even within a farm, there will be some fields much more likely to leach nitrate than others and, while farm practice plays a major role, soil type is massively influential and often overrides all other factors.

The terms critical source area or hot spot are often used to describe such locations, and where actions are required to reduce the overall load of N entering an estuary, it is important to target these high-risk locations.

Soil type has a very large impact on the risk of nitrate leaching for two reasons:

Soil texture determines the flow path water will take, overland flow on heavy, clayey soils or percolation down through free draining soils;De-nitrification is more likely on wet soils. Most nitrate lost to water occurs by leaching down through the soil.

The leaching process

Average nitrogen concentration levels in Ireland's rivers, 2019-2021. The yellow, orange and red colours signify the highest levels of nitrate concentration. \ EPA

To understand leaching, think of a bucket of moist sand with a porous bottom from which water can drain freely.

Rain falling on the bucket will move down through the sand and displace the same amount of moisture, plus any soluble material in that water, out through the bottom of the bucket.

If half the volume of the bucket is sand and half is water, 5mm of rain will displace 10mm of moisture downward.

In practice, when soils are wet (at field capacity), the soil texture will influence the depth to which existing soil water is displaced.

Soil water is pushed down two and a half times more in free draining sandy soils compared with heavy clay soils, where overland flow is far more likely.

In waterlogged soils, anaerobic bacteria (which grow in conditions with no oxygen) convert nitrate into gaseous compounds which are lost to the atmosphere.

This de-nitrification reduces water nitrate concentrations in much of the north and west of the country and even in drier parts of the south and east, existing wet areas in fields mitigate high nitrate in soil water flowing through them.

The Farming for Water EIP has recognised this and will fund the retention of such locations, which are often located beside watercourses.

As soils dry during summer, leaching stops. So, not only do actions for reducing nitrate loss to water need to be located in the right place, they also need to be done at the correct time of the year.

Next week’s article looks further into the seasonality of nitrate loss.

Edward Burgess works with the Agricultural Catchments Programme, which is informing many actions in Teagasc’s Better Farming for Water campaign.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently issued a report which gave nitrate concentrations in 20 Irish rivers a positive review, highlighting an improving (falling) trend in nitrate concentrations.

However, the document referenced catchments of concern, where nitrate concentrations need to be further reduced. The most downstream monitoring site on the rivers were used, giving a good indication of what is flowing into the estuary from the whole catchment.

Coastal and estuarine water is more impacted by nitrate than phosphorous, and these monitoring sites enable a calculation of the total amount (tonnes) of nitrogen entering the estuary from the catchment.

The term used to describe the amount of nitrogen (N) leaving a catchment is the ‘load’, which is calculated by multiplying the volume of water leaving the river (cubic meters) by the concentration (mg/l).

For example, 6,280t of nitrogen left the Slaney catchment in 2019. The Slaney estuary, from Enniscorthy to the mouth at Wexford Harbour, is receiving this load, and the concentration of nitrogen in the estuary is determined by how large a load is delivered.

Water quality

The green dots are nitrogen monitoring sites on Ireland's largest rivers. \ EPA

Ideally, for the estuary to have good ecological water quality, the average nitrogen concentration leaving the river as it enters the estuary should be below 2.6mg/l of N. (It is worth noting that the nitrate standard in water for human consumption is far less restrictive than the ecological limit – 11.3mg/l vs the 2.6mg N/l litre ecological standard).

Naturally, as a larger catchment drains a bigger area, you will have a greater volume and flow leaving, so it is easier to compare different catchments using the average nitrogen load for a given area, per hectare for example.

Many parts of this country typically get 1m of rainfall per year. Some 0.5m is taken up by growing plants through evapotranspiration, so the amount left flowing out our rivers is around 0.5m. This is called the “effective” rainfall. For half a meter of effective rainfall, a concentration of 2.6mg N/l is equivalent to 13kg N/ha.

While 13kg N/ha will possibly mean more to people than 2.6mg N/l, it is an average figure for the whole catchment.

There are always areas that are far riskier than others. Even within a farm, there will be some fields much more likely to leach nitrate than others and, while farm practice plays a major role, soil type is massively influential and often overrides all other factors.

The terms critical source area or hot spot are often used to describe such locations, and where actions are required to reduce the overall load of N entering an estuary, it is important to target these high-risk locations.

Soil type has a very large impact on the risk of nitrate leaching for two reasons:

Soil texture determines the flow path water will take, overland flow on heavy, clayey soils or percolation down through free draining soils;De-nitrification is more likely on wet soils. Most nitrate lost to water occurs by leaching down through the soil.

The leaching process

Average nitrogen concentration levels in Ireland's rivers, 2019-2021. The yellow, orange and red colours signify the highest levels of nitrate concentration. \ EPA

To understand leaching, think of a bucket of moist sand with a porous bottom from which water can drain freely.

Rain falling on the bucket will move down through the sand and displace the same amount of moisture, plus any soluble material in that water, out through the bottom of the bucket.

If half the volume of the bucket is sand and half is water, 5mm of rain will displace 10mm of moisture downward.

In practice, when soils are wet (at field capacity), the soil texture will influence the depth to which existing soil water is displaced.

Soil water is pushed down two and a half times more in free draining sandy soils compared with heavy clay soils, where overland flow is far more likely.

In waterlogged soils, anaerobic bacteria (which grow in conditions with no oxygen) convert nitrate into gaseous compounds which are lost to the atmosphere.

This de-nitrification reduces water nitrate concentrations in much of the north and west of the country and even in drier parts of the south and east, existing wet areas in fields mitigate high nitrate in soil water flowing through them.

The Farming for Water EIP has recognised this and will fund the retention of such locations, which are often located beside watercourses.

As soils dry during summer, leaching stops. So, not only do actions for reducing nitrate loss to water need to be located in the right place, they also need to be done at the correct time of the year.

Next week’s article looks further into the seasonality of nitrate loss.

Edward Burgess works with the Agricultural Catchments Programme, which is informing many actions in Teagasc’s Better Farming for Water campaign.

SHARING OPTIONS