The UK is in political turmoil, and it’s bad for Ireland.

It’s particularly bad for Irish farmers, for a whole pile of reasons.

Firstly, and most obviously, the UK is still a very important export market for Irish farming.

It mightn’t be as important as in our pre-EEC days, when it was by far the dominant export market for Irish food and drink, but one-third of our agri-food exports still go to the UK, with another third each to our EU partners and the rest of the world.

Since 2016, Ireland has been coping with the impact of Brexit on UK-EU trade, and more particularly Irish-UK trade.

The threat of third country duties on exports receded when the British Withdrawal Agreement was concluded in late 2019.

Then prime minister Boris Johnson described this as an “oven-ready” deal during the election he called following the agreement’s negotiation.

That was the last time the British people got to choose their leaders, and Boris and the Conservative Party gained a significant majority.

More chaos seems likely, and a reversal of the thawing between Brussels and Whitehall is entirely possible

However, the awkward question of how to manage the political and trade relationship between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland remained.

As the sole land border between the UK and the EU, it would be the friction point when the withdrawal agreement formally kicked in in early 2021.

Thus, the Northern Ireland Protocol was agreed in late 2020.

This effectively gave Northern Ireland “dual status” from a trade point of view, with goods from the EU and form the rest of the UK moving freely in (and out).

There was still a need to check what exactly was moving around to maintain the integrity of the EU’s single market, which is founded on an agreed and unique set of standards, standards which the UK and any new trading partners could freely choose to move away from.

The unionist community were dismayed by the fact that these checks would be conducted at the handful of ports across Northern Ireland.

It was practically sensible (there are about 300 road crossings across the north-south border) but politically sensitive.

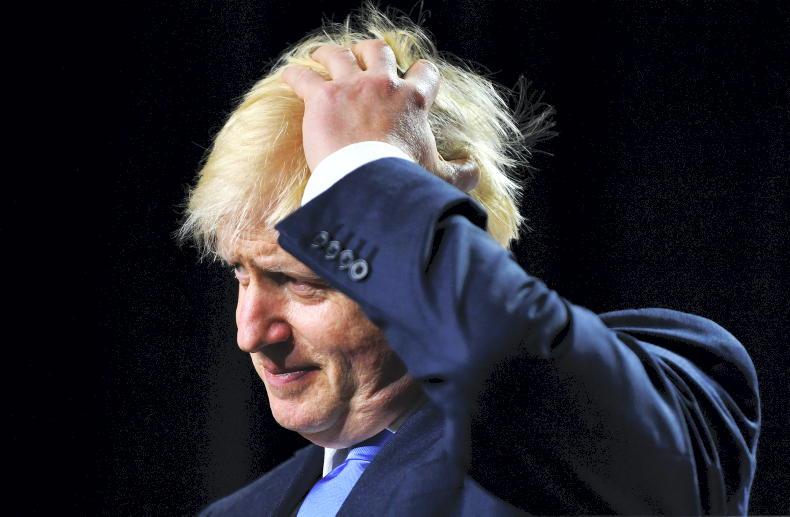

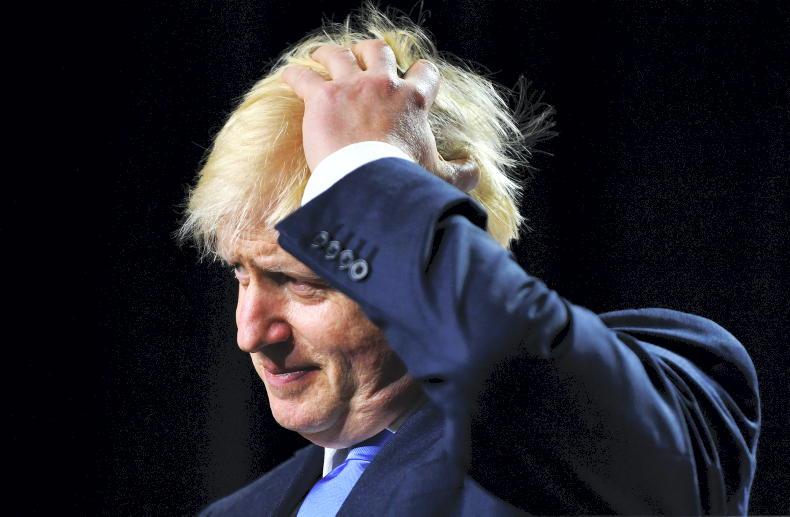

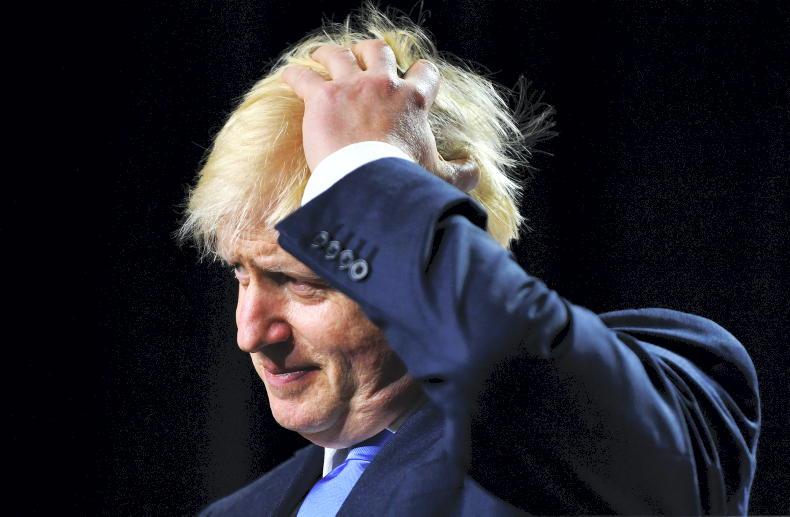

Boris Johnson. \ REUTERS/Dylan Martinez

The protocol means that the everyday cross-border movement of a huge range of agricultural commodities could continue without impediment, a goal of the Ulster Farmer Union as well as everybody in the Republic of Ireland.

Every day pigs and milk go north, sheep come south, and cattle go in both directions.

I’m located in Wexford, in the southeast of the country.

There is a fleet of milk lorries stationed here in Ferns to transport milk across the border to Strathroy. That milk is kept apart from British milk. I can buy it back here in Ferns with the Origin Green logo on it.

Even slurry crosses the border. We are utterly interwoven as an island of food producers.

There is also a continuing relationship between Ireland and the UK as a “single market” in an entirely different context.

Because we are two countries across two islands (with some smaller islands), Ireland has often been an add-on to the British market for products.

Post-Brexit, this means the double-whammy of two new separate import duty charges, one into the UK from the EU, and another into the Republic of Ireland from the UK.

Tractor and machine parts, pesticides, and animal health products routed through the UK are all either suffering these charges (and associated processing delays) or finding a new direct route to the Irish market.

Pull down the Protocol

The DUP has been working to pull the protocol down since it was agreed.

In the latter days of Johnson’s premiership, it seemed like the party was making progress, as the UK became more hardline about what kind of permanent political and trade arrangement we would have on this island.

Then Boris Johnson was forced out of office following a succession of political and personal scandals.

In July, 57 ministers resigned in a single day rather than continue to serve under him.

Liz Truss was appointed to succeed him. She pushed an extreme right-wing free-market economic agenda and appointed ultra-Brexiteers Chris Heaton-Harris and Steve Baker as secretary of state and minister of state for Northern Ireland.

However, there was an immediate improvement in relations between the UK and Brussels.

Just read this quote from Steve Baker: “I want to accept and acknowledge that I and others did not always behave in a way which encouraged Ireland and the European Union to trust us to accept that they have legitimate interests ... And I am sorry about that because relations with Ireland are not where they should be and we will need to work extremely hard to improve them and I know that we are doing so.”

That was earlier this month at the Conservative Party Conference, and sounded like the turning over of a page.

But now Liz Truss is gone, and we have to wait and see what approach a new prime minister will bring to relations with Brussels and Dublin.

And it’s looking increasingly like the new prime minister could be an old prime minister.

Is Boris on the way back?

Brexit is a little like a wedding certificate. The latter shows that you are now married, but it has no bearing on what kind of relationship you now have, whether with your marriage partner or with others.

Similarly, Brexit was a licence for the UK to leave the European Union, but there was no indication as to what kind of relationship the UK would have with its neighbours as it settled into its new domestic arrangements.

The crucial external question concerned the customs union. There was the option for the UK to opt out of the political union of the EU, but remain within the single market.

Indeed, that was what many of the pro-Brexit advocates campaigned on during the referendum debate, and presumably what many pro-Brexit voters thought they were endorsing.

But as soon as the result came in, the hardliners’ voices were the loudest.

The phrase “Brexit in name only” was born to describe the more moderate approach.

As in so many things, this was borrowed from the politics of the new right in the US. They coined the acronym “RINO” to describe anyone who was a member of the Republican Party, but in any way “liberal” on gun control, taxation, universal healthcare, or reproductive rights - “Republican in name only”.

And just as Donald Trump emerged as the face of this brash, selfish, macho mindset, Boris Johnson became the de-facto leader of the pro-Brexit wing in the Conservative Party.

He was essential to the referendum win - more charismatic, colourful and convincing than his former Bullingdon club co-member David Cameron.

Theresa May. \ Number 10

His predecessor as prime minister, Theresa May, coined the phrase “Brexit means Brexit”.

This was either profound or utterly meaningless, depending on your perspective. But it certainly emboldened the hardline Brexiteers the European Research Group (ERG) who pushed Theresa May towards a hard Brexit, out of any formal trading relationship with the EU.

They eventually forced her put of office.

The ERG is an assembly of Conservative MPs who had been campaigning for Britain to get out of Europe since the early 1990s.

They were formed as then prime minister John Major was wrestling with the Maastricht Treaty. He famously referred to Eurosceptic ministers as “bastards” in an off-air remark picked up by a stray microphone at the time.

In that same conversation, he spoke of “a party that is still harking back to a golden age that never was, and is now invented”.

He was referring to the Thatcher era as a glorified fiction only three years after it had ended.

This week we had an eerie echo of those events as Channel 4 news anchor Krishnan Guru-Murthy used even less parliamentary language to describe the aforementioned Steve Baker following an interview between them on Wednesday night as the government crumbled.

Now, Boris Johnson could be returning to power.

If he does, I doubt he will have learned a thing from his short enforced exile, other than that people have incredibly short memories, and that a brass neck can prevail.

More chaos seems likely, and a reversal of the thawing between Brussels and Whitehall is entirely possible.

Lowering standards

Back in 2018, I suggested that a strategy of lowering your standards to attract new partners was one I would never advise to a friend. I think the same applies to a country.

Brexit was the realisation of the ambition for Britain to pursue a path back to what John Major wisely described as “a golden age that never was”.

And while the UK wrestles with its future in the world, we as their closest neighbours can only hope they don’t wreck their own economy.

If their house goes on fire, mainland Europe may have to deal with the plumes of smoke.

Semi-detached, Ireland will probably be engulfed in the flames, economic and political.

The UK is in political turmoil, and it’s bad for Ireland.

It’s particularly bad for Irish farmers, for a whole pile of reasons.

Firstly, and most obviously, the UK is still a very important export market for Irish farming.

It mightn’t be as important as in our pre-EEC days, when it was by far the dominant export market for Irish food and drink, but one-third of our agri-food exports still go to the UK, with another third each to our EU partners and the rest of the world.

Since 2016, Ireland has been coping with the impact of Brexit on UK-EU trade, and more particularly Irish-UK trade.

The threat of third country duties on exports receded when the British Withdrawal Agreement was concluded in late 2019.

Then prime minister Boris Johnson described this as an “oven-ready” deal during the election he called following the agreement’s negotiation.

That was the last time the British people got to choose their leaders, and Boris and the Conservative Party gained a significant majority.

More chaos seems likely, and a reversal of the thawing between Brussels and Whitehall is entirely possible

However, the awkward question of how to manage the political and trade relationship between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland remained.

As the sole land border between the UK and the EU, it would be the friction point when the withdrawal agreement formally kicked in in early 2021.

Thus, the Northern Ireland Protocol was agreed in late 2020.

This effectively gave Northern Ireland “dual status” from a trade point of view, with goods from the EU and form the rest of the UK moving freely in (and out).

There was still a need to check what exactly was moving around to maintain the integrity of the EU’s single market, which is founded on an agreed and unique set of standards, standards which the UK and any new trading partners could freely choose to move away from.

The unionist community were dismayed by the fact that these checks would be conducted at the handful of ports across Northern Ireland.

It was practically sensible (there are about 300 road crossings across the north-south border) but politically sensitive.

Boris Johnson. \ REUTERS/Dylan Martinez

The protocol means that the everyday cross-border movement of a huge range of agricultural commodities could continue without impediment, a goal of the Ulster Farmer Union as well as everybody in the Republic of Ireland.

Every day pigs and milk go north, sheep come south, and cattle go in both directions.

I’m located in Wexford, in the southeast of the country.

There is a fleet of milk lorries stationed here in Ferns to transport milk across the border to Strathroy. That milk is kept apart from British milk. I can buy it back here in Ferns with the Origin Green logo on it.

Even slurry crosses the border. We are utterly interwoven as an island of food producers.

There is also a continuing relationship between Ireland and the UK as a “single market” in an entirely different context.

Because we are two countries across two islands (with some smaller islands), Ireland has often been an add-on to the British market for products.

Post-Brexit, this means the double-whammy of two new separate import duty charges, one into the UK from the EU, and another into the Republic of Ireland from the UK.

Tractor and machine parts, pesticides, and animal health products routed through the UK are all either suffering these charges (and associated processing delays) or finding a new direct route to the Irish market.

Pull down the Protocol

The DUP has been working to pull the protocol down since it was agreed.

In the latter days of Johnson’s premiership, it seemed like the party was making progress, as the UK became more hardline about what kind of permanent political and trade arrangement we would have on this island.

Then Boris Johnson was forced out of office following a succession of political and personal scandals.

In July, 57 ministers resigned in a single day rather than continue to serve under him.

Liz Truss was appointed to succeed him. She pushed an extreme right-wing free-market economic agenda and appointed ultra-Brexiteers Chris Heaton-Harris and Steve Baker as secretary of state and minister of state for Northern Ireland.

However, there was an immediate improvement in relations between the UK and Brussels.

Just read this quote from Steve Baker: “I want to accept and acknowledge that I and others did not always behave in a way which encouraged Ireland and the European Union to trust us to accept that they have legitimate interests ... And I am sorry about that because relations with Ireland are not where they should be and we will need to work extremely hard to improve them and I know that we are doing so.”

That was earlier this month at the Conservative Party Conference, and sounded like the turning over of a page.

But now Liz Truss is gone, and we have to wait and see what approach a new prime minister will bring to relations with Brussels and Dublin.

And it’s looking increasingly like the new prime minister could be an old prime minister.

Is Boris on the way back?

Brexit is a little like a wedding certificate. The latter shows that you are now married, but it has no bearing on what kind of relationship you now have, whether with your marriage partner or with others.

Similarly, Brexit was a licence for the UK to leave the European Union, but there was no indication as to what kind of relationship the UK would have with its neighbours as it settled into its new domestic arrangements.

The crucial external question concerned the customs union. There was the option for the UK to opt out of the political union of the EU, but remain within the single market.

Indeed, that was what many of the pro-Brexit advocates campaigned on during the referendum debate, and presumably what many pro-Brexit voters thought they were endorsing.

But as soon as the result came in, the hardliners’ voices were the loudest.

The phrase “Brexit in name only” was born to describe the more moderate approach.

As in so many things, this was borrowed from the politics of the new right in the US. They coined the acronym “RINO” to describe anyone who was a member of the Republican Party, but in any way “liberal” on gun control, taxation, universal healthcare, or reproductive rights - “Republican in name only”.

And just as Donald Trump emerged as the face of this brash, selfish, macho mindset, Boris Johnson became the de-facto leader of the pro-Brexit wing in the Conservative Party.

He was essential to the referendum win - more charismatic, colourful and convincing than his former Bullingdon club co-member David Cameron.

Theresa May. \ Number 10

His predecessor as prime minister, Theresa May, coined the phrase “Brexit means Brexit”.

This was either profound or utterly meaningless, depending on your perspective. But it certainly emboldened the hardline Brexiteers the European Research Group (ERG) who pushed Theresa May towards a hard Brexit, out of any formal trading relationship with the EU.

They eventually forced her put of office.

The ERG is an assembly of Conservative MPs who had been campaigning for Britain to get out of Europe since the early 1990s.

They were formed as then prime minister John Major was wrestling with the Maastricht Treaty. He famously referred to Eurosceptic ministers as “bastards” in an off-air remark picked up by a stray microphone at the time.

In that same conversation, he spoke of “a party that is still harking back to a golden age that never was, and is now invented”.

He was referring to the Thatcher era as a glorified fiction only three years after it had ended.

This week we had an eerie echo of those events as Channel 4 news anchor Krishnan Guru-Murthy used even less parliamentary language to describe the aforementioned Steve Baker following an interview between them on Wednesday night as the government crumbled.

Now, Boris Johnson could be returning to power.

If he does, I doubt he will have learned a thing from his short enforced exile, other than that people have incredibly short memories, and that a brass neck can prevail.

More chaos seems likely, and a reversal of the thawing between Brussels and Whitehall is entirely possible.

Lowering standards

Back in 2018, I suggested that a strategy of lowering your standards to attract new partners was one I would never advise to a friend. I think the same applies to a country.

Brexit was the realisation of the ambition for Britain to pursue a path back to what John Major wisely described as “a golden age that never was”.

And while the UK wrestles with its future in the world, we as their closest neighbours can only hope they don’t wreck their own economy.

If their house goes on fire, mainland Europe may have to deal with the plumes of smoke.

Semi-detached, Ireland will probably be engulfed in the flames, economic and political.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: