Imagine for a moment that the government brought in a new regulation that all cars, petrol or diesel, with engines over two-litres capacity would operate under strict conditions.

Owners would have to show just cause, such as four or more children, or to tow a trailer. Ownership of a trailer would be required, and a towbar essential. You would have to use Google maps on your car’s computer to show where and when you’d travelled, so the car might have to be up-specced. You could only use high-grade fuel, and Ad-Blu would be essential for diesel engines. You could still drive a car of between two-litres and three-litre engine capacity, but only under these strict conditions. And if someone gained penalty points while driving this car, for any reason, the license to drive this larger car would be revoked for a year.

Higher output

In a way, that’s what the nitrates derogation is like. A license to have a higher output farm in exchange for a strict set of oversight conditions and a commitment to operate your farm to the highest standards.

And about 7,000 farmers have signed up for this arrangement and have built their farms around it. And about 3,000 of these farmers are operating at the upper end of the organic nitrates range between 220kg and 249kg of organic nitrogen per hectare.

Now, imagine that the Government come along and say Brussels are adjusting the rules around large car engines.

Instead of a maximum engine size of three litres, the new maximum car size, subject to the strict conditions, is 2.7 litres. And this change will be implemented from 1 January 2024.

Imagine being a car owner who has just bought a three-litre car or has bought a trailer that would require a three-litre car to tow it. Now the car has to go and a big financial hit is looming.

The whole business is built around a model that has just been undermined

That is a crude analogy for what it’s like to be a dairy farmer in derogation at the moment. The whole business is built around a model that has just been undermined.

Farmer fear, anger and upset is understandable. But is it justified? That’s not as easy a question to answer.

A succession of usually articulate farmer representatives have struggled to say on what grounds the reduction to 220kg should be reversed. It’s one thing to highlight the damage this will do to individual farmers, it’s quite another to make a convincing case to leave the 250kg in place until 2026.

Farmers are angry that the Government hasn’t put enough into the campaign to keep the status quo. And I get that. But the question now has to be what do farmers want that can be gotten and how are they going to get it?

It is true that there is technically a way of stopping this, but it’s a narrow path that would require the expending of political capital. Leo Varadkar as Taoiseach would have to intervene personally with Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, to get her to override the decision of Commissioner Sinkevicius. The Taoiseach has already ruled this option out, and that's no surprise, it was always unlikely that he would expend precious brownie points on an issue that, at a national level, is a fringe issue.

Even if Leo Varadkar were prepared to, I’m not sure it would have been the best use of resources. The current nitrates directive will end on 31 December 2025. Ireland will need to negotiate a new directive.

By then, Commissioner Sinkevicius will probably be replaced and his replacement will bring in their own senior cabinet staff.

Ursula von der Leyen will also have completed her term and we will have an entirely new European Parliament.

But the permanent secretariat within Brussels will be unchanged and these officials are likely to remember if Ireland have gone over their heads. It could be a case of buy (an escape clause) now, pay later. And it will be dairy farmers paying.

Hard truths were avoided for too long

Any accusation of lack of leadership from Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue should centre less on whether he met the Commissioner face to face as opposed to a Zoom meeting. The optics of an online meeting aren’t great, but the outcome wouldn’t have changed.

The reality is that if Charlie McConalogue, Tim Cullinan, Pat McCormack and Stephen Arthur had gone on hunger strike on the steps of the Berlaymont building (where the Commission resides), the outcome wouldn’t have changed.

The lack of leadership, rather, should look at the refusal of the Minister to say what has been blindingly obvious for at least three years now.

Dairy expansion had reached its natural limit in many parts of the country somewhere around 2020. Not because farmers had run out of ambition or dairy processors had exhausted the market for Irish dairy product, but because of the combination of environmental constraints that were coming down the tracks. Cow numbers had maxed out, considering the combination of environmental limits that were coming into operation in tandem.

But no-one was willing to say the unpalatable truth, that we were stretching the limits of dairy expansion

But no-one was willing to say the unpalatable truth, that we were stretching the limits of dairy expansion. Not just the Minister and politicians, but also within the industry.

Farm leaders, co-op chairs and ceo’s all talked as if expansion could and should continue forever. We heard about aeroplanes and Brazilian deforestation, and Irelands natural advantage in growing grass and turning it into milk. The mantra was no forced reduction of the national herd. But realistically, we were heading for the buffers the moment the programme for government was agreed. The climate action plan is not compatible with continuing expansion of cattle numbers in the country. And now the Nitrates Directive has jumped ahead of it, directly impacting on cow numbers on more highly stocked farms from next January.

Farmers heard what they wanted to hear and believed the narrative that they were entitled to belt away, increasing cow numbers. And now they are looking at cuts in cow numbers of up to 15% on their farms. Cuts which have to happen next year.

Solutions

So, what can be done? Firstly, of course, the Irish Farmers' Association (IFA) and the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers' Association (ICMSA) owe it to dairy farmers to fight to the end for the best possible outcome.

However, the reality is that the best outcome no longer includes the option of 250kg across the country in 2024. The new reality is 220kg. Because of this, a package of support measures is urgently needed.

Firstly, slurry offset could be made available as an alternative to cutting cow numbers for derogation farmers as a transitional measure.

Tillage and low-stocked dairy farmers would need to be incentivised to take in slurry, which will lower their chemical fertiliser usage.

In addition, derogation farmers, who are among the most efficient nutrient users in European farming, could be allowed to lower chemical fertiliser within their overall nitrates (and phosphate) budget, again as a transitional measure to allow for managed change.

These two measures would only be in place until 2026, to help farmers adjust.

The advent of multispecies swards and increased clover usage is reducing chemical fertiliser usage while maintaining grass output on dairy farms.

That is surely a win-win for the environment. The new fertiliser register means there will be an effective track-and-trace system for chemical fertiliser on every dairy farm in the country.

Cessation scheme

I also think that the concept of a dairy cessation scheme must be revisited in the light of the new realities. It should target older farmers without successors and pay them generously to give up their cows.

Other dairy farmers could then extend their grazing platform across this land, allowing them to maintain cow numbers. There is still both a reduction on overall cow numbers and a reduction in stocking rate across the overall land-base in question.

And what about anaerobic digestion (AD) as an end use of slurry rather than land spreading?

The Government has been much better at administering the stick of environmental regulation than delivering the carrot of promised solutions.

Minister for the Environment Eamon Ryan has committed to 200 AD plants by the end of the decade - are there even 10 at planning stage two years into the climate action plan?

How about setting up a high-level group, involving Eamon Ryan, Charlie McConalogue, senior officials, dairy processors and dairy farmer representatives to build a network of AD plants that would take in slurry from dairy farms. Offsets could be granted for delivery of slurry to such plants.

We now need AD plants on the ground in less than six months and that is not possible; but with fast-track planning and stakeholder buy-in, we certainly could have them in place in 18 months.

There is a further reality. Slurry storage is a significant issue on many dairy farms and could force cuts in cow numbers more than the 220kg restriction.

Firstly, we have a lengthening closed period. The extra week both this year and next require a 15% increase in slurry storage. Then there are the changed rules around when dirty water can be land-spread during the closed period. They require extra storage space.

Furthermore, there are whisperings around the cubic metre allocation of slurry storage required per cow.

A revision could be on the cards and we know that revisions are always upwards when it comes to farming and environmental restrictions.

Off-grid is not the solution

I’m also hearing that some dairy farmers are considering going off-grid rather than accept the new restrictions. What does this mean?

The idea is that farmers will sell, lease or revoke their entitlements and not make a direct payment application at all in future years. No BISS, no CRISS, no eco schemes, no eligibility.

The belief is being expressed that this will allow a farmer to belt away at their preferred stocking rate, under the radar as it were.

The Department will still know through AIMS what livestock a farmer has, but it won’t know the amount of land that stock is being carried on.

I think this is misguided, bordering on reckless. Firstly, the nitrates directive is utterly separate to the direct payment system. There is a link, in that there is cross-reporting of nitrates breaches as a non-compliance issue that can lead to direct payment penalties.

But deciding not to take the carrots offered will not mean being liberated from the stick of regulation and enforcement.

Local authorities can and do come on farm, demanding to see your slurry storage and asking for the maps of the land you are farming.

Fisheries have similar powers of inspection and the Department can come and inspect your farm at any time. And being quality assured (QA) is now pretty much essential for any farm. Does anyone seriously think a QA inspection will be passed without confirming the grazing platform?

And there won’t be any wriggle room as regards borrowing a few fields. Realistically, there might be a few acre plots in each parish that aren’t already accounted for in the BISS field identification system, but that’s about it. It’s not like heading off into the Australian outback or the wilds of Alaska to forge your own path, is it?

There’s another issue. The Department is likely to regard any farm going off-grid as high risk. It’s a strategy likely to attract inspection.

And if the authorities find any breach of nitrates regulations, they have plenty of ways of inflicting punishment on the offending farmer.

Stability

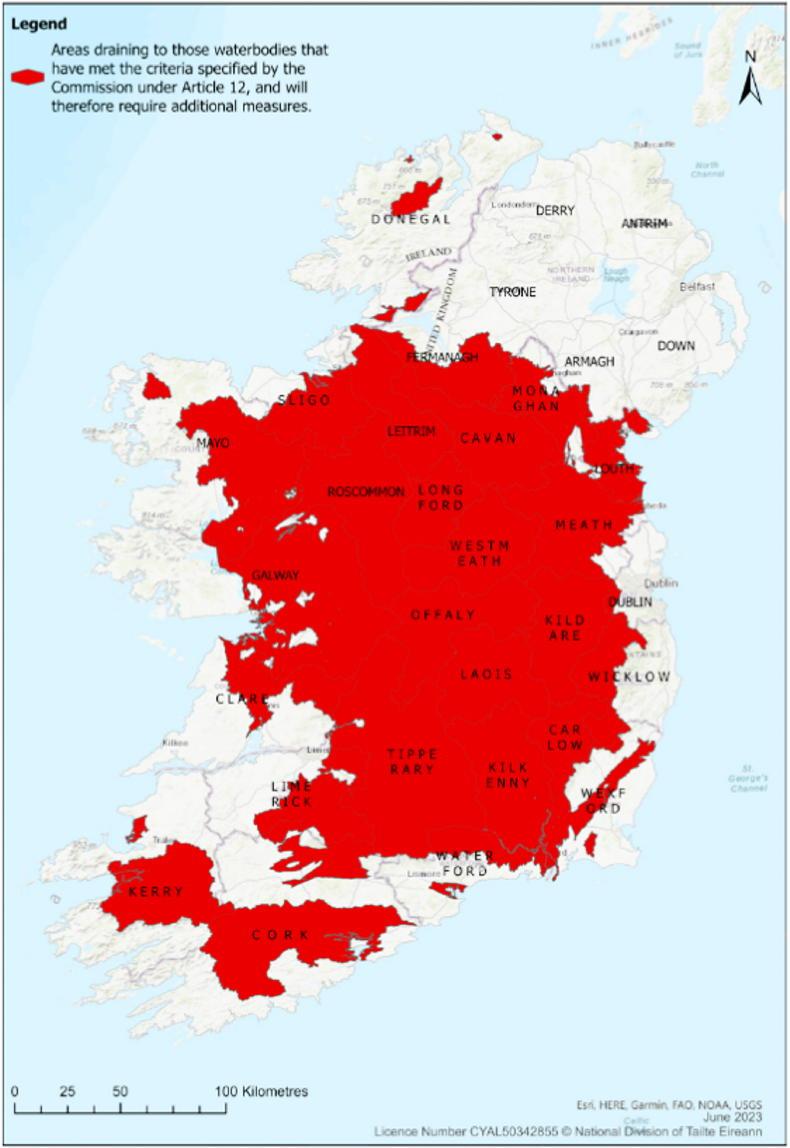

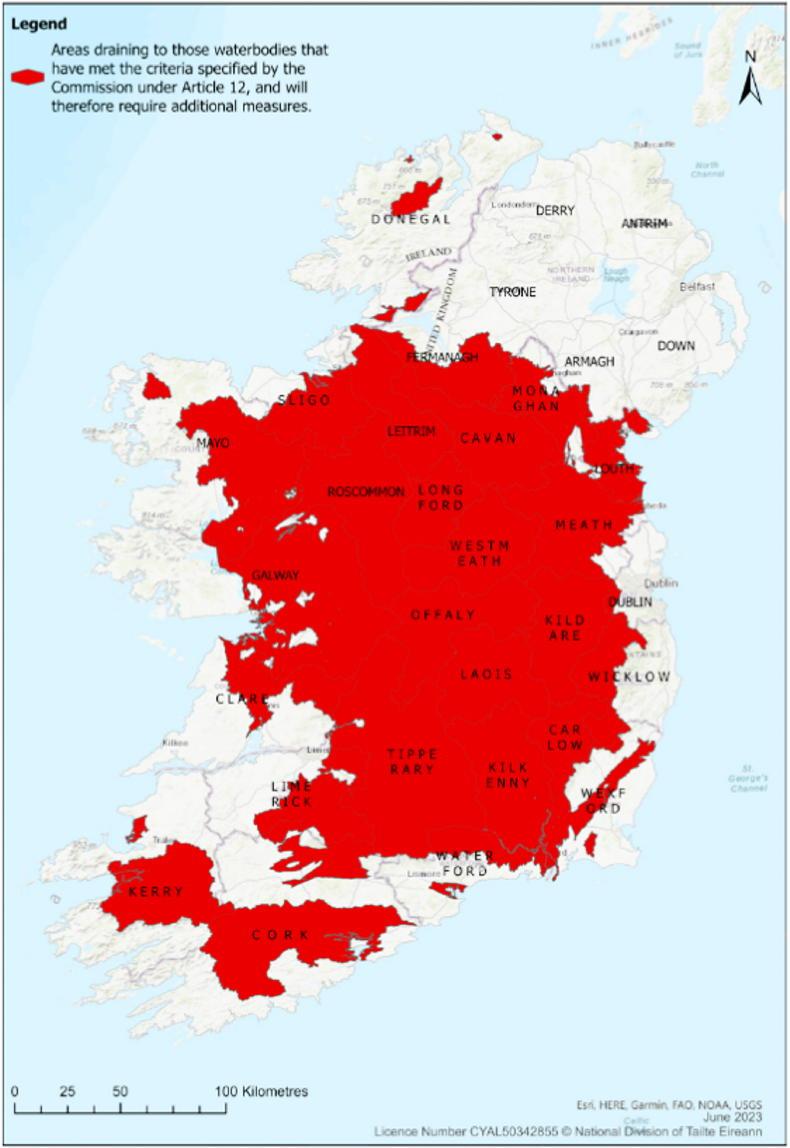

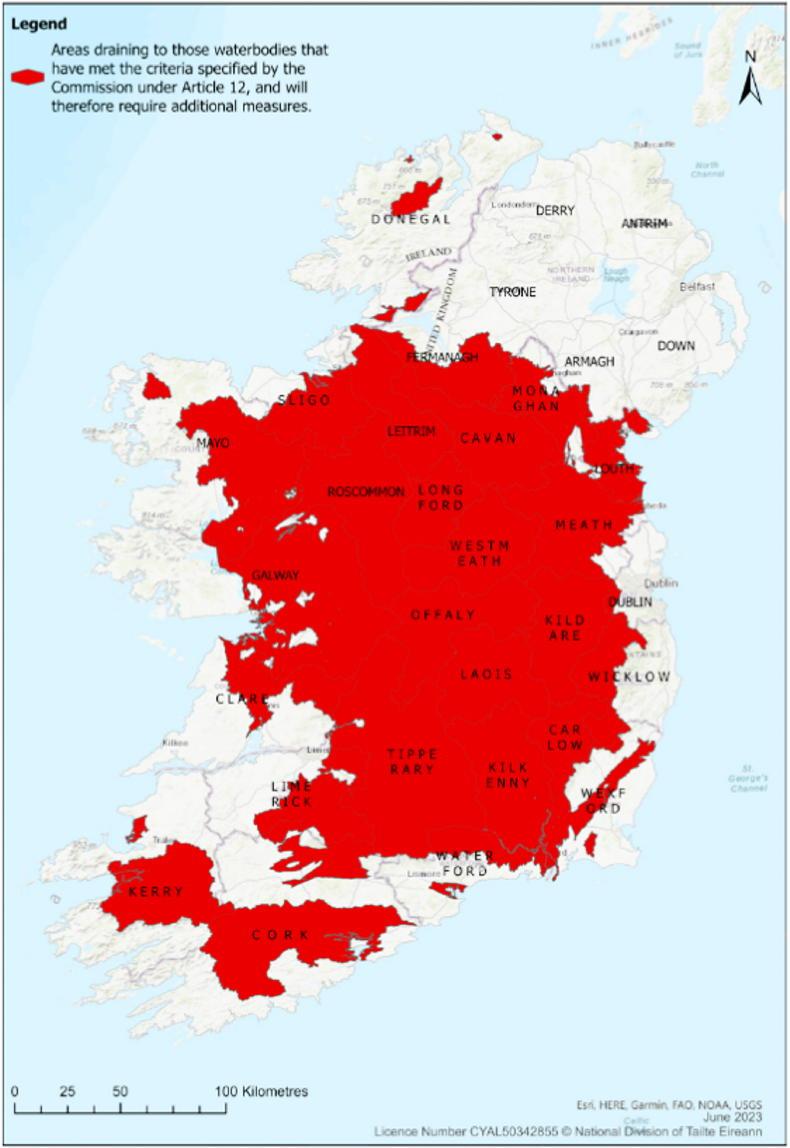

Above all, what dairy farmers now need is stability. I don’t see any way around the new 220kg limit where maps show that water quality has not improved.

Most derogation farmers are in the red zones on the maps and, as more measuring takes place, the expectation is that the map will get more red, not less.

A map of the areas where the derogation will be cut to 220kg N/ha from January.

So perhaps more than anything, the Government needs to gain assurances from the Commission that it will be given a reasonable period of time for its businesses to absorb this change. And 2026 is not a reasonable period of time in that context.

A further cut in a little over two years’ time would put many dairy farms under. There needs to be a commitment from the Commission that the next nitrates directive will be based on 220kg/250kg organic N, not 195kg/220kg.

If the 2026-2029 directive is consistent with this one, that gives farmers five years to absorb the hit to their bottom line.

To revisit the analogy this article began with, don’t change from 3l to 2.7l and then in 2026 change from 2.7l to 2.4l. That would be one blow too many.

Imagine for a moment that the government brought in a new regulation that all cars, petrol or diesel, with engines over two-litres capacity would operate under strict conditions.

Owners would have to show just cause, such as four or more children, or to tow a trailer. Ownership of a trailer would be required, and a towbar essential. You would have to use Google maps on your car’s computer to show where and when you’d travelled, so the car might have to be up-specced. You could only use high-grade fuel, and Ad-Blu would be essential for diesel engines. You could still drive a car of between two-litres and three-litre engine capacity, but only under these strict conditions. And if someone gained penalty points while driving this car, for any reason, the license to drive this larger car would be revoked for a year.

Higher output

In a way, that’s what the nitrates derogation is like. A license to have a higher output farm in exchange for a strict set of oversight conditions and a commitment to operate your farm to the highest standards.

And about 7,000 farmers have signed up for this arrangement and have built their farms around it. And about 3,000 of these farmers are operating at the upper end of the organic nitrates range between 220kg and 249kg of organic nitrogen per hectare.

Now, imagine that the Government come along and say Brussels are adjusting the rules around large car engines.

Instead of a maximum engine size of three litres, the new maximum car size, subject to the strict conditions, is 2.7 litres. And this change will be implemented from 1 January 2024.

Imagine being a car owner who has just bought a three-litre car or has bought a trailer that would require a three-litre car to tow it. Now the car has to go and a big financial hit is looming.

The whole business is built around a model that has just been undermined

That is a crude analogy for what it’s like to be a dairy farmer in derogation at the moment. The whole business is built around a model that has just been undermined.

Farmer fear, anger and upset is understandable. But is it justified? That’s not as easy a question to answer.

A succession of usually articulate farmer representatives have struggled to say on what grounds the reduction to 220kg should be reversed. It’s one thing to highlight the damage this will do to individual farmers, it’s quite another to make a convincing case to leave the 250kg in place until 2026.

Farmers are angry that the Government hasn’t put enough into the campaign to keep the status quo. And I get that. But the question now has to be what do farmers want that can be gotten and how are they going to get it?

It is true that there is technically a way of stopping this, but it’s a narrow path that would require the expending of political capital. Leo Varadkar as Taoiseach would have to intervene personally with Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, to get her to override the decision of Commissioner Sinkevicius. The Taoiseach has already ruled this option out, and that's no surprise, it was always unlikely that he would expend precious brownie points on an issue that, at a national level, is a fringe issue.

Even if Leo Varadkar were prepared to, I’m not sure it would have been the best use of resources. The current nitrates directive will end on 31 December 2025. Ireland will need to negotiate a new directive.

By then, Commissioner Sinkevicius will probably be replaced and his replacement will bring in their own senior cabinet staff.

Ursula von der Leyen will also have completed her term and we will have an entirely new European Parliament.

But the permanent secretariat within Brussels will be unchanged and these officials are likely to remember if Ireland have gone over their heads. It could be a case of buy (an escape clause) now, pay later. And it will be dairy farmers paying.

Hard truths were avoided for too long

Any accusation of lack of leadership from Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue should centre less on whether he met the Commissioner face to face as opposed to a Zoom meeting. The optics of an online meeting aren’t great, but the outcome wouldn’t have changed.

The reality is that if Charlie McConalogue, Tim Cullinan, Pat McCormack and Stephen Arthur had gone on hunger strike on the steps of the Berlaymont building (where the Commission resides), the outcome wouldn’t have changed.

The lack of leadership, rather, should look at the refusal of the Minister to say what has been blindingly obvious for at least three years now.

Dairy expansion had reached its natural limit in many parts of the country somewhere around 2020. Not because farmers had run out of ambition or dairy processors had exhausted the market for Irish dairy product, but because of the combination of environmental constraints that were coming down the tracks. Cow numbers had maxed out, considering the combination of environmental limits that were coming into operation in tandem.

But no-one was willing to say the unpalatable truth, that we were stretching the limits of dairy expansion

But no-one was willing to say the unpalatable truth, that we were stretching the limits of dairy expansion. Not just the Minister and politicians, but also within the industry.

Farm leaders, co-op chairs and ceo’s all talked as if expansion could and should continue forever. We heard about aeroplanes and Brazilian deforestation, and Irelands natural advantage in growing grass and turning it into milk. The mantra was no forced reduction of the national herd. But realistically, we were heading for the buffers the moment the programme for government was agreed. The climate action plan is not compatible with continuing expansion of cattle numbers in the country. And now the Nitrates Directive has jumped ahead of it, directly impacting on cow numbers on more highly stocked farms from next January.

Farmers heard what they wanted to hear and believed the narrative that they were entitled to belt away, increasing cow numbers. And now they are looking at cuts in cow numbers of up to 15% on their farms. Cuts which have to happen next year.

Solutions

So, what can be done? Firstly, of course, the Irish Farmers' Association (IFA) and the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers' Association (ICMSA) owe it to dairy farmers to fight to the end for the best possible outcome.

However, the reality is that the best outcome no longer includes the option of 250kg across the country in 2024. The new reality is 220kg. Because of this, a package of support measures is urgently needed.

Firstly, slurry offset could be made available as an alternative to cutting cow numbers for derogation farmers as a transitional measure.

Tillage and low-stocked dairy farmers would need to be incentivised to take in slurry, which will lower their chemical fertiliser usage.

In addition, derogation farmers, who are among the most efficient nutrient users in European farming, could be allowed to lower chemical fertiliser within their overall nitrates (and phosphate) budget, again as a transitional measure to allow for managed change.

These two measures would only be in place until 2026, to help farmers adjust.

The advent of multispecies swards and increased clover usage is reducing chemical fertiliser usage while maintaining grass output on dairy farms.

That is surely a win-win for the environment. The new fertiliser register means there will be an effective track-and-trace system for chemical fertiliser on every dairy farm in the country.

Cessation scheme

I also think that the concept of a dairy cessation scheme must be revisited in the light of the new realities. It should target older farmers without successors and pay them generously to give up their cows.

Other dairy farmers could then extend their grazing platform across this land, allowing them to maintain cow numbers. There is still both a reduction on overall cow numbers and a reduction in stocking rate across the overall land-base in question.

And what about anaerobic digestion (AD) as an end use of slurry rather than land spreading?

The Government has been much better at administering the stick of environmental regulation than delivering the carrot of promised solutions.

Minister for the Environment Eamon Ryan has committed to 200 AD plants by the end of the decade - are there even 10 at planning stage two years into the climate action plan?

How about setting up a high-level group, involving Eamon Ryan, Charlie McConalogue, senior officials, dairy processors and dairy farmer representatives to build a network of AD plants that would take in slurry from dairy farms. Offsets could be granted for delivery of slurry to such plants.

We now need AD plants on the ground in less than six months and that is not possible; but with fast-track planning and stakeholder buy-in, we certainly could have them in place in 18 months.

There is a further reality. Slurry storage is a significant issue on many dairy farms and could force cuts in cow numbers more than the 220kg restriction.

Firstly, we have a lengthening closed period. The extra week both this year and next require a 15% increase in slurry storage. Then there are the changed rules around when dirty water can be land-spread during the closed period. They require extra storage space.

Furthermore, there are whisperings around the cubic metre allocation of slurry storage required per cow.

A revision could be on the cards and we know that revisions are always upwards when it comes to farming and environmental restrictions.

Off-grid is not the solution

I’m also hearing that some dairy farmers are considering going off-grid rather than accept the new restrictions. What does this mean?

The idea is that farmers will sell, lease or revoke their entitlements and not make a direct payment application at all in future years. No BISS, no CRISS, no eco schemes, no eligibility.

The belief is being expressed that this will allow a farmer to belt away at their preferred stocking rate, under the radar as it were.

The Department will still know through AIMS what livestock a farmer has, but it won’t know the amount of land that stock is being carried on.

I think this is misguided, bordering on reckless. Firstly, the nitrates directive is utterly separate to the direct payment system. There is a link, in that there is cross-reporting of nitrates breaches as a non-compliance issue that can lead to direct payment penalties.

But deciding not to take the carrots offered will not mean being liberated from the stick of regulation and enforcement.

Local authorities can and do come on farm, demanding to see your slurry storage and asking for the maps of the land you are farming.

Fisheries have similar powers of inspection and the Department can come and inspect your farm at any time. And being quality assured (QA) is now pretty much essential for any farm. Does anyone seriously think a QA inspection will be passed without confirming the grazing platform?

And there won’t be any wriggle room as regards borrowing a few fields. Realistically, there might be a few acre plots in each parish that aren’t already accounted for in the BISS field identification system, but that’s about it. It’s not like heading off into the Australian outback or the wilds of Alaska to forge your own path, is it?

There’s another issue. The Department is likely to regard any farm going off-grid as high risk. It’s a strategy likely to attract inspection.

And if the authorities find any breach of nitrates regulations, they have plenty of ways of inflicting punishment on the offending farmer.

Stability

Above all, what dairy farmers now need is stability. I don’t see any way around the new 220kg limit where maps show that water quality has not improved.

Most derogation farmers are in the red zones on the maps and, as more measuring takes place, the expectation is that the map will get more red, not less.

A map of the areas where the derogation will be cut to 220kg N/ha from January.

So perhaps more than anything, the Government needs to gain assurances from the Commission that it will be given a reasonable period of time for its businesses to absorb this change. And 2026 is not a reasonable period of time in that context.

A further cut in a little over two years’ time would put many dairy farms under. There needs to be a commitment from the Commission that the next nitrates directive will be based on 220kg/250kg organic N, not 195kg/220kg.

If the 2026-2029 directive is consistent with this one, that gives farmers five years to absorb the hit to their bottom line.

To revisit the analogy this article began with, don’t change from 3l to 2.7l and then in 2026 change from 2.7l to 2.4l. That would be one blow too many.

SHARING OPTIONS