An ordinary farming family’s battle to survive on a small west of Ireland holding through the travails of the 19th century and the seismic changes of the early 20th century is the subject of a fascinating online exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland – Country Life.

In 2023, the museum – which is based at Turlough House, Co Mayo – acquired a donation of 40 well-preserved documents. The documents cover 150 years of life on the land occupied by the Murray family in the townland of Knockrawer in the rural south Sligo parish of Kilturra.

From the earliest document dated 1809 to the last from the mid-20th century, the documents provide a glimpse into the life of this farming family.

Though associated with the small farm of their forebearers, the Murray documents show the influence official Ireland had on the working lives and financial health of a typical farming family in Ireland.

The townland of Knockrawer is located 35km south of Sligo town, close to the village of Gurteen. According to the earliest document in the collection, the occupier of the Murray farm was Pat Murray, then spelled Patt Murry.

Later, the Tithe Applotment Book for the parish of Kilturra, dated 1833, records several Murrays occupying land in the townland of Knockrawer. Tithe Applotment Books were completed for most rural Church of Ireland parishes.

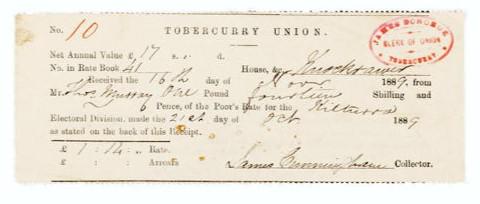

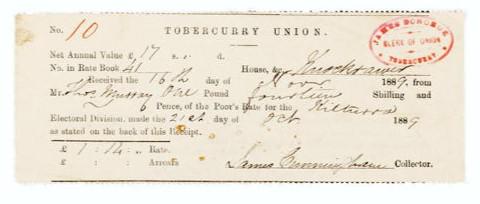

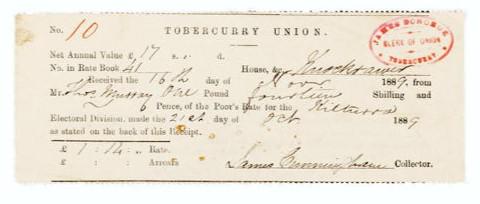

Receipt for poor law payment.

Based on the quantity and quality of land held by an occupier, a tithe or tax payable to the Church of Ireland was determined.

The tithe was also to be paid by Catholic families such as the Murrays.

Patt Murry held just over 10ac and 23 perches of land, four acres and two roods of which were classified as arable. A rood was one quarter of an acre and a perch one fortieth of a rood. This would have classified Murray as a small farmer.

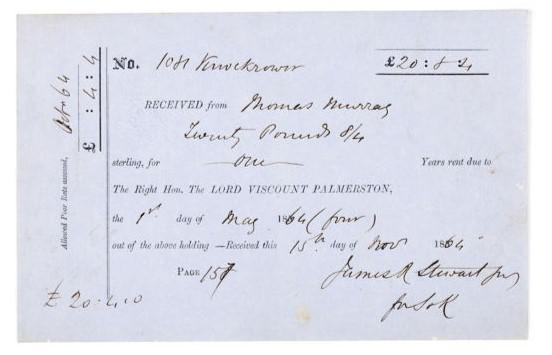

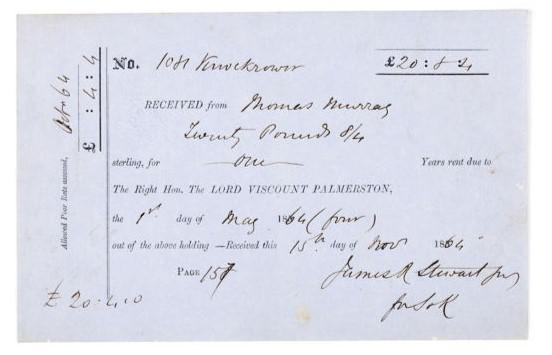

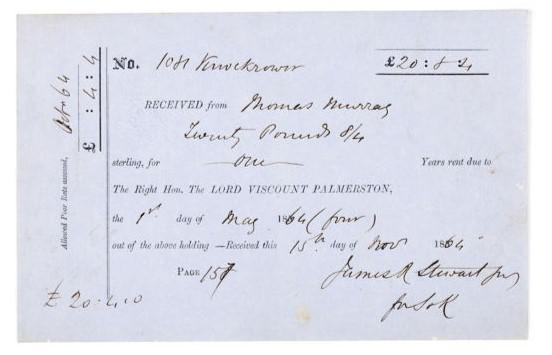

A rent receipt received from the Palmerston Estate by the Murray family.

Landlord

Patt Murry’s landlord at this time was Henry John Temple, third Viscount Palmerston. Palmerston visited his Sligo estates for the first time in 1808. Not unfeeling toward his Irish tenants on what he accepted was poor land, Palmerston observed that his tenants were too poor to improve their land and yet he could not bring himself to evict them.

Lord Palmerston later served as prime minister of the United Kingdom on two occasions.

As recorded in Griffiths Valuation for the townland of Knockrawer in 1857, Thomas, Michael, Martin and Michael Murray Jr all rented land of equal value from Lord Palmerston, which amounted to 119ac in total. It is not known what farming was carried out by the Murrays. However, in general, but unlike other counties in Connacht in the immediate aftermath of the Great Famine, Sligo farmers concentrated on cattle rather than sheep.

Total acreage under crops, most notably corn and oats, fell dramatically in the county as the 19th century progressed.

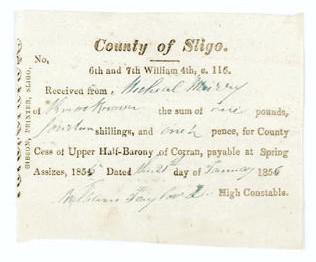

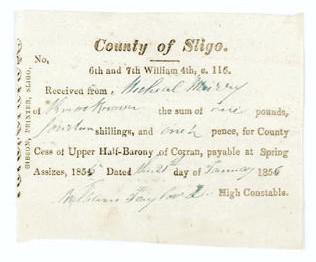

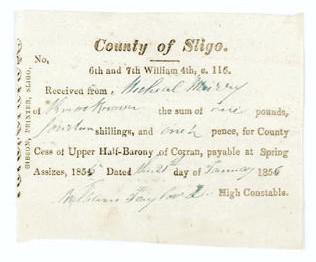

County cess payment for 1855.

The collection of Murray documents tells us much about the various rates and levies imposed on farming families.

The Murrays were expected to pay not only the tithe and their rent, but also a poor rate.

The government attempted to ease the plight of the poor by passing ‘The Act for the more effectual Relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland’ into law in 1838.

The law provided for the division of Ireland into unions, each centred on a market town and comprising the rural hinterland of about 10 miles in radius. A board of guardians would run each union. Each board was to finance the running of a workhouse by striking a poor rate to be exacted from all eligible people in the union.

On top of the poor rate and existing duties, grand juries were authorised to collect money through a county rate or cess for a variety of purposes, mainly related to the construction of infrastructure and the upkeep of institutions. By the early 20th century, the Murrays were also making payments to the Irish Land Commission.

A selection of the Murray documents is now available to view as an online exhibition on museum.ie and is complemented by a series of three online talks.

Whiteboyism to land ownership

In 1905, Michael Murray Jr purchased the land in Knockrawer from his landlords for £351. Interest on the purchase money was payable to the Irish Land Commission by Murray at a rate of 3.5% per annum.

The purchase of the lands was made under the provision of the Irish Land Act of 1903, and through the Irish Land Commission.

The Land Act of 1881 had provided for the establishment of the Irish Land Commission. The Land Commission initially settled rent disputes between landlord and tenant but as land reform progressed, the Land Commission’s importance grew.

Under the Land Act of 1881, tenant Thomas Murray applied to the Land Commission Court to fix a fair rent. A tenant, or landlord and tenant jointly, could apply to the land court for rent to be fixed.

Murray’s landlords at the time were Elizabeth Mary Hippisley (née Sullivan) and her sister Charlotte Antonia Sullivan who were nieces of Lord Palmerston. Palmerston had died in 1865.

Thomas Murray’s application to the Land Commission in 1881 came at the height of the Land War, when tenants demanded fairer rents.

Destruction of landlord property was sometimes organised by tenants in an effort to force their demands.

‘Whiteboysim’ became a general term used by the courts and the press for all agrarian violence carried out by secret societies. Pat and Michael Murray of Knockrawer appeared in court in 1880, accused of carrying out acts of whiteboyism in their townland the previous year.

Land purchases

The land purchases which the land acts of the late 19th century facilitated meant that the Land Commission essentially became the new landlord.

Documents in the collection show that the gale days for the payment of Murray’s half-yearly instalments of the purchase annuities under the Irish Land Act, 1903, were 1 June and 1 December in each year.

If the advance was not made on one of the gale days, then penalties were applied. Gale days were traditionally the days on which rent was due.

The Irish Land Commission remained responsible for the redistribution farmland.

It was eventually abolished in 1999.

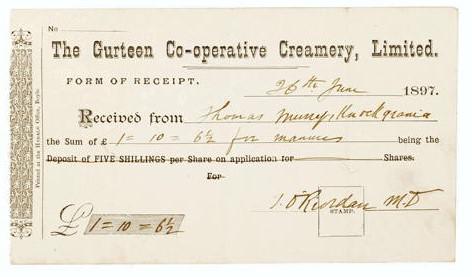

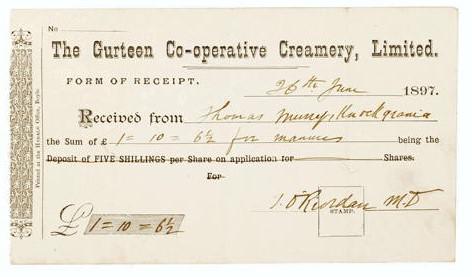

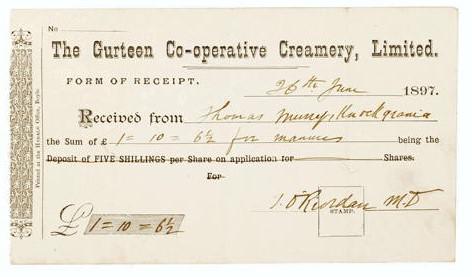

Receipt for purchase of shareholding in Gurteen Co-operative Creamery.

Surviving famine and

the threat of eviction

Although the Murrays managed to hold their lands and survive the ravages of the Great Famine, the documents show that this was a serious struggle.

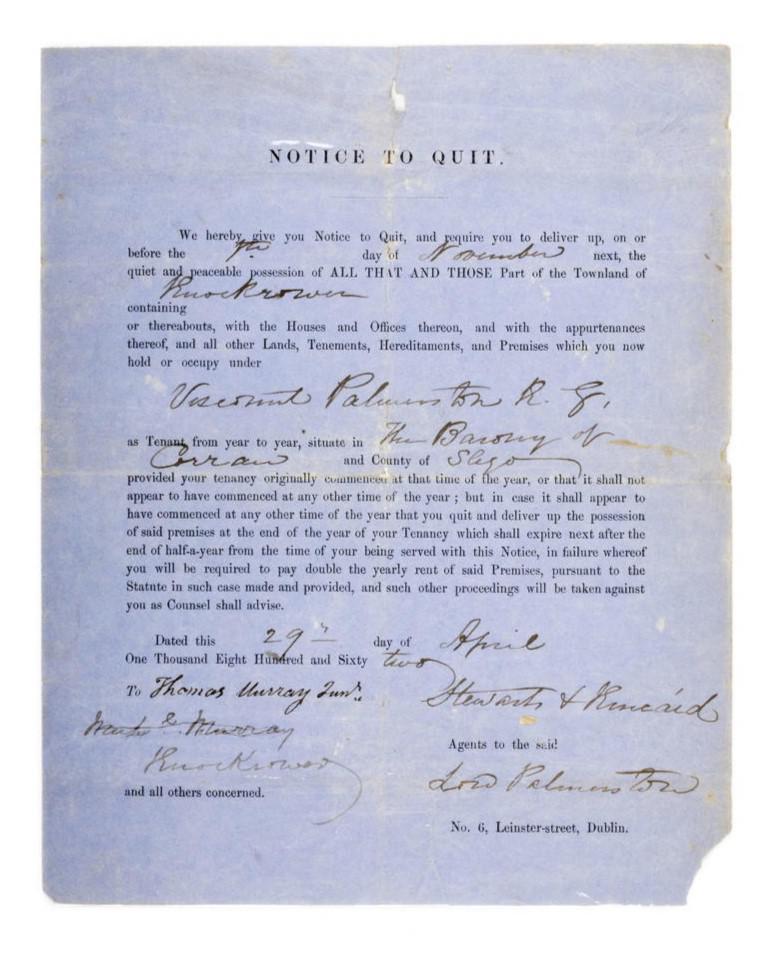

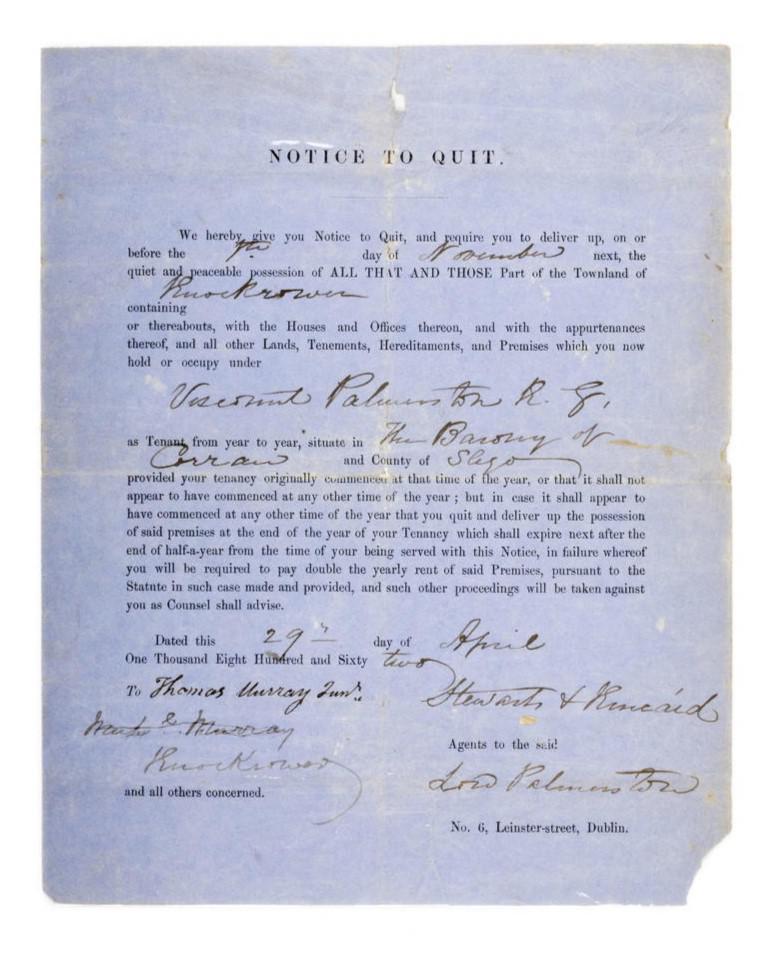

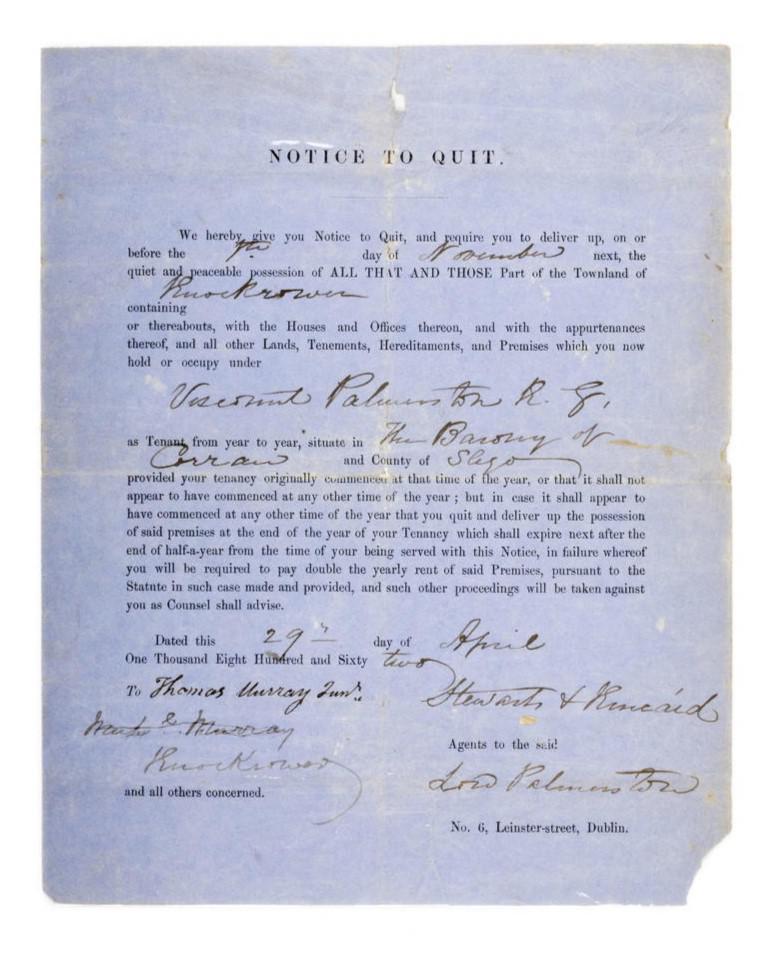

A Notice to Quit was served on tenants Thomas and Michael Murray of Knockrawer by Stewarts and Kincaid, agents to The Right Honourable Henry John Viscount Palmerston, at the height of the Great Famine in February 1847.

The notice required the Murrays to deliver up the quiet and peaceable possession of 20ac they rented in Knockrawer.

Serving a Notice to Quit did not necessarily lead to an eviction. Tenants were given time to pay the arrears owed. The Murrays clearly managed to pay off the arrears owed, as they did on at least two more occasions later over the following four decades.

In 1847, Palmerston assisted about 2,000 of his Sligo tenants to emigrate to British North America.

Eviction notice served on the Murrays; the collection includes three such notices issued between 1847 and 1883.

According to the Murray family, one of their descendants sailed from Sligo on the ‘Carricks of Whitehaven’ for Quebec in March that year. The voyage was funded by Palmsteron. In May, with its destination in sight, the brig struck a reef in the Gulf of St Lawrence. Of the 173 passengers on board, only 48 completed the journey.

Another Notice to Quit was later served on tenant Thomas Murray Jr, by Palmerston through his agents Stewarts and Kincaid in 1862, and a further notice in 1883.

The arrears owed in 1883 exceeded £56, which was more than two and a half times the annual rent of £22 10s.

Ironically, the 1883 ejectment notice was issued on St Patrick’s Day.

Dodgy horses and drainage

The Murray collection includes a number of documents, which detail the more mundane dealings and disputes which characterised farming life.

Among these is a handwritten letter dated 5 March 1841 – which was signed by Michel Murry [Michael Murray] – demanding the return of £11 that was paid to Edward McDonaugh for a horse. Murray protests that the horse was not fit to be sold.

Murray purchased the horse from McDonaugh at a fair of Ballinagar. However, the following day the new owner discovered that the animal had a blood spavin.

In his letter to McDonaugh, which is available to read online, Murray gives notice that either the money is returned, or he will sell the horse at public auction in Tubbercurry and will sue McDonaugh for any loss he sustains. The collection also records local co-operative developments and the costs of river drainage schemes for farmers.

The Murrays clearly saw the benefits of co-operatives and became shareholders in 1897 in Gurteen Co-operative Creamery.

Meanwhile, under the River Owenmore Drainage Act, 1926, a drainage rate was made in relation to lands that were said to have been drained or improved and was assessed on the rated occupiers of those lands. Sligo County Council adopted the drainage rate. The Murrays’ land was located within the river’s catchment area and a rate was imposed on them.

Background Noel Campbell is a curator with the National Museum of Ireland - Country Life

An ordinary farming family’s battle to survive on a small west of Ireland holding through the travails of the 19th century and the seismic changes of the early 20th century is the subject of a fascinating online exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland – Country Life.

In 2023, the museum – which is based at Turlough House, Co Mayo – acquired a donation of 40 well-preserved documents. The documents cover 150 years of life on the land occupied by the Murray family in the townland of Knockrawer in the rural south Sligo parish of Kilturra.

From the earliest document dated 1809 to the last from the mid-20th century, the documents provide a glimpse into the life of this farming family.

Though associated with the small farm of their forebearers, the Murray documents show the influence official Ireland had on the working lives and financial health of a typical farming family in Ireland.

The townland of Knockrawer is located 35km south of Sligo town, close to the village of Gurteen. According to the earliest document in the collection, the occupier of the Murray farm was Pat Murray, then spelled Patt Murry.

Later, the Tithe Applotment Book for the parish of Kilturra, dated 1833, records several Murrays occupying land in the townland of Knockrawer. Tithe Applotment Books were completed for most rural Church of Ireland parishes.

Receipt for poor law payment.

Based on the quantity and quality of land held by an occupier, a tithe or tax payable to the Church of Ireland was determined.

The tithe was also to be paid by Catholic families such as the Murrays.

Patt Murry held just over 10ac and 23 perches of land, four acres and two roods of which were classified as arable. A rood was one quarter of an acre and a perch one fortieth of a rood. This would have classified Murray as a small farmer.

A rent receipt received from the Palmerston Estate by the Murray family.

Landlord

Patt Murry’s landlord at this time was Henry John Temple, third Viscount Palmerston. Palmerston visited his Sligo estates for the first time in 1808. Not unfeeling toward his Irish tenants on what he accepted was poor land, Palmerston observed that his tenants were too poor to improve their land and yet he could not bring himself to evict them.

Lord Palmerston later served as prime minister of the United Kingdom on two occasions.

As recorded in Griffiths Valuation for the townland of Knockrawer in 1857, Thomas, Michael, Martin and Michael Murray Jr all rented land of equal value from Lord Palmerston, which amounted to 119ac in total. It is not known what farming was carried out by the Murrays. However, in general, but unlike other counties in Connacht in the immediate aftermath of the Great Famine, Sligo farmers concentrated on cattle rather than sheep.

Total acreage under crops, most notably corn and oats, fell dramatically in the county as the 19th century progressed.

County cess payment for 1855.

The collection of Murray documents tells us much about the various rates and levies imposed on farming families.

The Murrays were expected to pay not only the tithe and their rent, but also a poor rate.

The government attempted to ease the plight of the poor by passing ‘The Act for the more effectual Relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland’ into law in 1838.

The law provided for the division of Ireland into unions, each centred on a market town and comprising the rural hinterland of about 10 miles in radius. A board of guardians would run each union. Each board was to finance the running of a workhouse by striking a poor rate to be exacted from all eligible people in the union.

On top of the poor rate and existing duties, grand juries were authorised to collect money through a county rate or cess for a variety of purposes, mainly related to the construction of infrastructure and the upkeep of institutions. By the early 20th century, the Murrays were also making payments to the Irish Land Commission.

A selection of the Murray documents is now available to view as an online exhibition on museum.ie and is complemented by a series of three online talks.

Whiteboyism to land ownership

In 1905, Michael Murray Jr purchased the land in Knockrawer from his landlords for £351. Interest on the purchase money was payable to the Irish Land Commission by Murray at a rate of 3.5% per annum.

The purchase of the lands was made under the provision of the Irish Land Act of 1903, and through the Irish Land Commission.

The Land Act of 1881 had provided for the establishment of the Irish Land Commission. The Land Commission initially settled rent disputes between landlord and tenant but as land reform progressed, the Land Commission’s importance grew.

Under the Land Act of 1881, tenant Thomas Murray applied to the Land Commission Court to fix a fair rent. A tenant, or landlord and tenant jointly, could apply to the land court for rent to be fixed.

Murray’s landlords at the time were Elizabeth Mary Hippisley (née Sullivan) and her sister Charlotte Antonia Sullivan who were nieces of Lord Palmerston. Palmerston had died in 1865.

Thomas Murray’s application to the Land Commission in 1881 came at the height of the Land War, when tenants demanded fairer rents.

Destruction of landlord property was sometimes organised by tenants in an effort to force their demands.

‘Whiteboysim’ became a general term used by the courts and the press for all agrarian violence carried out by secret societies. Pat and Michael Murray of Knockrawer appeared in court in 1880, accused of carrying out acts of whiteboyism in their townland the previous year.

Land purchases

The land purchases which the land acts of the late 19th century facilitated meant that the Land Commission essentially became the new landlord.

Documents in the collection show that the gale days for the payment of Murray’s half-yearly instalments of the purchase annuities under the Irish Land Act, 1903, were 1 June and 1 December in each year.

If the advance was not made on one of the gale days, then penalties were applied. Gale days were traditionally the days on which rent was due.

The Irish Land Commission remained responsible for the redistribution farmland.

It was eventually abolished in 1999.

Receipt for purchase of shareholding in Gurteen Co-operative Creamery.

Surviving famine and

the threat of eviction

Although the Murrays managed to hold their lands and survive the ravages of the Great Famine, the documents show that this was a serious struggle.

A Notice to Quit was served on tenants Thomas and Michael Murray of Knockrawer by Stewarts and Kincaid, agents to The Right Honourable Henry John Viscount Palmerston, at the height of the Great Famine in February 1847.

The notice required the Murrays to deliver up the quiet and peaceable possession of 20ac they rented in Knockrawer.

Serving a Notice to Quit did not necessarily lead to an eviction. Tenants were given time to pay the arrears owed. The Murrays clearly managed to pay off the arrears owed, as they did on at least two more occasions later over the following four decades.

In 1847, Palmerston assisted about 2,000 of his Sligo tenants to emigrate to British North America.

Eviction notice served on the Murrays; the collection includes three such notices issued between 1847 and 1883.

According to the Murray family, one of their descendants sailed from Sligo on the ‘Carricks of Whitehaven’ for Quebec in March that year. The voyage was funded by Palmsteron. In May, with its destination in sight, the brig struck a reef in the Gulf of St Lawrence. Of the 173 passengers on board, only 48 completed the journey.

Another Notice to Quit was later served on tenant Thomas Murray Jr, by Palmerston through his agents Stewarts and Kincaid in 1862, and a further notice in 1883.

The arrears owed in 1883 exceeded £56, which was more than two and a half times the annual rent of £22 10s.

Ironically, the 1883 ejectment notice was issued on St Patrick’s Day.

Dodgy horses and drainage

The Murray collection includes a number of documents, which detail the more mundane dealings and disputes which characterised farming life.

Among these is a handwritten letter dated 5 March 1841 – which was signed by Michel Murry [Michael Murray] – demanding the return of £11 that was paid to Edward McDonaugh for a horse. Murray protests that the horse was not fit to be sold.

Murray purchased the horse from McDonaugh at a fair of Ballinagar. However, the following day the new owner discovered that the animal had a blood spavin.

In his letter to McDonaugh, which is available to read online, Murray gives notice that either the money is returned, or he will sell the horse at public auction in Tubbercurry and will sue McDonaugh for any loss he sustains. The collection also records local co-operative developments and the costs of river drainage schemes for farmers.

The Murrays clearly saw the benefits of co-operatives and became shareholders in 1897 in Gurteen Co-operative Creamery.

Meanwhile, under the River Owenmore Drainage Act, 1926, a drainage rate was made in relation to lands that were said to have been drained or improved and was assessed on the rated occupiers of those lands. Sligo County Council adopted the drainage rate. The Murrays’ land was located within the river’s catchment area and a rate was imposed on them.

Background Noel Campbell is a curator with the National Museum of Ireland - Country Life

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: