Why would an astute businessman buy a historical property with a less-than-stellar historical record in terms of its tenants and spend 40 years trying to tell its story?

“That very short answer is insanity,” Caroilin Callery tells Irish Country Living as we sip tea in the bright, modern café of the Strokestown Park Famine Museum.

And she would know, being the daughter of Jim Callery, the businessman that purchased the Co Roscommon estate in 1979.

“I was very young when the Westward Group bought the property, with the intention of holding the land for the Scania business and selling it [the house] on.”

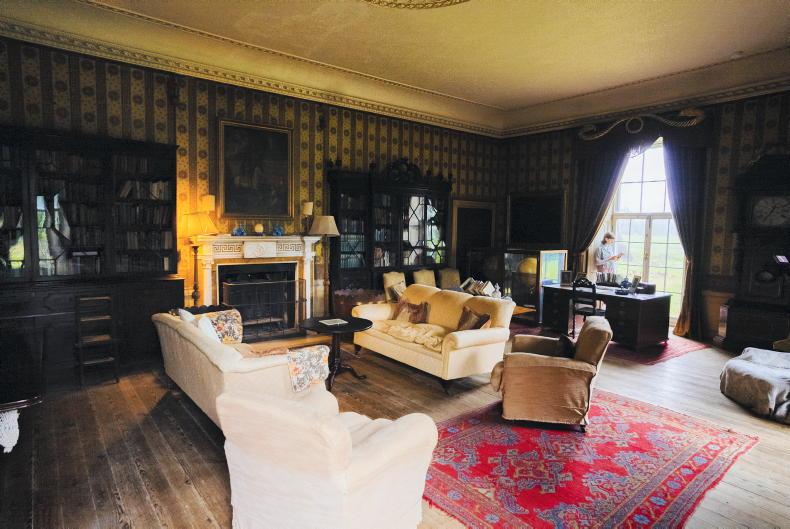

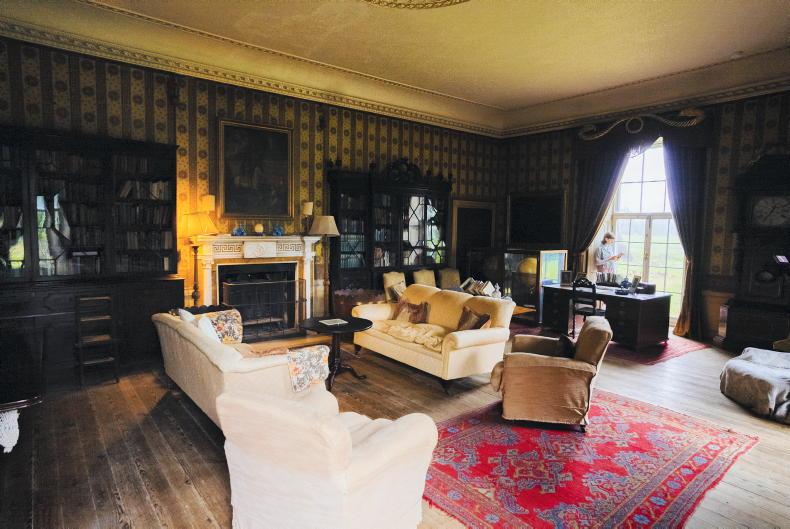

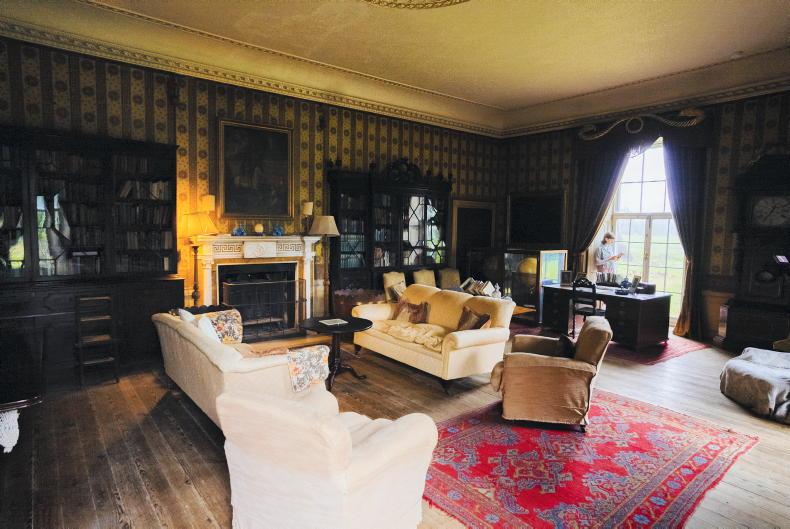

Every corner of the house holds a story, which guide John O’Sullivan expertly explains.

Jim had allowed the previous owner, Olive Pakenham Mahon, to stay living at the house and a “friendship of sorts” had grown between them.

The weekend the contents of the property were being lined up for auction, Olive was travelling to London to visit her children. Jim asked if he could “look around”, to which she replied, “Of course, Mr Callery, it’s your house now.”

Cloonahee petition

That one visit changed the future of Strokestown Park forever.

The first room he went into was the smoking room with its leaky roof and boxes, floor to ceiling. One of the first things that Jim took out of the first box he opened was the Cloonahee Petition, which is now on display in the museum.

Caroilin explains the significance of this finding.

Caroilin and Jim Callery walked the Famine Way together from Strokestown to Dublin

“That is the townland where my father’s family have lived for hundreds of years. All of the names, Caulfields, McHughs and McDermotts – all those families – are still in that townland and that was from 1846. It [the petition] was literally saying ‘We’re starving, we went to the public works, we were turned away, what are we to do? We don’t want to do anything unless pressed to by hunger.’

“In that one moment, the fate of Strokestown Park was changed forever. Did it find him or did he find it? Dad put the document back and the next time he spoke to Olive, he said he would buy the contents of the house if they left the archive. He understood what he stumbled on, that this story wasn’t told, wasn’t talked about and that what he was saving was vital.”

Hidden history to modern museum

When the families left the big houses, everything was auctioned off and scattered. They also, in general, burnt the archives or if they did give them up, it was to the State and many took out the decades of famine.

“They understood,” Caroilin notes, “how it would reflect on most of the families, not all but most, how they treated their tenants at that time.”

For many years, Jim dipped in and out of the archive, with a professional archivist, Martin Fagan, employed only in the last four years. With the archive now catalogued, it’s been made available.

The house opened in 1987 but the vision immediately was to use the archive to tell the story of the famine. To the Callerys, this made perfect sense as “this was the microcosm of what was the macrocosm, of what was happening everywhere else around the country.”

However, not everyone agreed and when the famine museum opened in 1994 there was a lot of criticism on how appropriate the house was as a location.

“We weren’t far from the burnings and dismantling of big houses as that image of British dominance in Ireland. Some of the people that criticised in those early years later admitted that, this is where the story should be told,” says Caroilin.

While operated since 2015 by the Irish Heritage Trust (IHT), the museum itself opened in 1994 and the gardens in 1998. Although the recent renovation has added considerable modernity and comfort to the park Caroilin says: “It’s a never-ending labour of love and philanthropy from my father.”

Famine way

An outreach from Strokestown Park, in partnership with Waterways Ireland, the IHT, Epic Museum and a host of academic institutions, The Famine Way is a trail charting the journey of the 1490 tenants who walked from Strokestown Park to Dublin to the coffin ships that would take them to Canada.

There are 32 pairs of bronze shoes, placed at specific locations where there is a story in relation to the famine. The first pair and the trailhead are at Stokestown Park.

One of the main stories recounted in the famine museum is that of Daniel, who lost all his family bar one little sister. They were adopted by a French Canadian family going on to inherit their farm. His grandson Leo lived with him and heard him tell his story. Jim Callery met Leo, who was then nearly 90, and heard the story.

How close in time this is resonates with Caroilin.

“That was in 2000, not that long ago to be getting first-hand knowledge. The famine isn’t as far back as we think it is and that’s why it’s so embedded in our psyche. We all know about the ships, but what about their last journey on Irish soil?”

In 2015, Caroilin and a group of friends did the walk, as a memorial. As they went through each of the counties, they put out a call for people to join them and were caught by surprise at the number that did and the subsequent media attention.

From that, a conversation arose with Waterways Ireland about turning it into the permanent trail officially launched in 2019.

But it was not history but modern-day geopolitics that was really brought home to Caroilin on this trip.

“On our second day walking in Ballynacarrigy [Westmeath], I got a phone call to tell me that a ship had turned over off the coast of Italy and 600 people had drowned,” she explains.

“That really bothered me because I thought this is what happened to our people. People who were not going to make it, people that were going to find the sea as their grave. I thought, how can this still be happening? How can our past be somebody else’s present?

“We have reached out to work with New Horizons, the emigration group in Athlone. They walked along the trail with us and we have had joint events here. Dad would say: ‘If this is just a museum telling the history, then it’s a dead museum.

“You are duty-bound to use the archive and story to shine a light on what’s happening today in other parts of the world that are similar. Because this isn’t just an old story from our past, this is very much other people’s stories now.”

The unhidden

baron heartlands

Fascinating was the word I kept repeating on my tour from the house, through the equine cathedral to the museum itself. Irish Country Living was guided by expert John O Driscoll, ably assisted by the IHT’s Tony Aspel.

Nicholas Mahon was granted the lands for his services to Cromwell in the late 1600s but it was his grandson, Thomas Mahan, who hired Richard Castles – the German architect who designed Leinster House – to design Strokestown House in the 1740s. For their support of the Act of Union, the family was granted a title – becoming known as the Baron Heartlands of Strokestown.

The first Baron built what is described as the widest street in Ireland. John is very proud to claim that the main street in Strokestown is wider than O’Connell Street, but also admits: “I don’t believe it but I’ve been told I have to accept it.”

Thomas wanted his street to mimic the Champs-Élysées. John asks if I knew that Strokestown is lovingly called the Paris of the west. “No,” I admit, while assuring him I would make sure to communicate this epithet to my readers.

The story of the 1490

The last Baron “Poor Maurice” saw the estate fall into massive debt. On his death, the estate went to his cousin Major Dennis Mahon in 1845. This was where the story of the Strokestown famine walkers begins.

“A debt-ridden estate, the beginning of the great Irish famine, many rent strikes. What was he to do?” John recounts.

“Well, the first thing that happened was wonderful. His daughter Grace Catherine married Henry Sandford Pakenham, the combined lands went up to 30,000 acres at this time and the name changed to Packenham Mahon. On the advice of an agent John Ross Mahon, he began an eviction and immigration scheme to clear his lands. He gathered 1490 men, women and children and had them walk from Strokestown to Dublin along the Royal Canal for ships to Quebec. By the time they got there more than a third of them had died.”

Shortly after, Denis Mahon was assassinated. No member of the family lived at the house after that until Henry Packenham Mahon came to live here and it was his daughter, Olive that sold the estate to Jim Callery.

Read more

Cavan’s hidden heartlands

Building an adventure centre on a farm from the water up

Why would an astute businessman buy a historical property with a less-than-stellar historical record in terms of its tenants and spend 40 years trying to tell its story?

“That very short answer is insanity,” Caroilin Callery tells Irish Country Living as we sip tea in the bright, modern café of the Strokestown Park Famine Museum.

And she would know, being the daughter of Jim Callery, the businessman that purchased the Co Roscommon estate in 1979.

“I was very young when the Westward Group bought the property, with the intention of holding the land for the Scania business and selling it [the house] on.”

Every corner of the house holds a story, which guide John O’Sullivan expertly explains.

Jim had allowed the previous owner, Olive Pakenham Mahon, to stay living at the house and a “friendship of sorts” had grown between them.

The weekend the contents of the property were being lined up for auction, Olive was travelling to London to visit her children. Jim asked if he could “look around”, to which she replied, “Of course, Mr Callery, it’s your house now.”

Cloonahee petition

That one visit changed the future of Strokestown Park forever.

The first room he went into was the smoking room with its leaky roof and boxes, floor to ceiling. One of the first things that Jim took out of the first box he opened was the Cloonahee Petition, which is now on display in the museum.

Caroilin explains the significance of this finding.

Caroilin and Jim Callery walked the Famine Way together from Strokestown to Dublin

“That is the townland where my father’s family have lived for hundreds of years. All of the names, Caulfields, McHughs and McDermotts – all those families – are still in that townland and that was from 1846. It [the petition] was literally saying ‘We’re starving, we went to the public works, we were turned away, what are we to do? We don’t want to do anything unless pressed to by hunger.’

“In that one moment, the fate of Strokestown Park was changed forever. Did it find him or did he find it? Dad put the document back and the next time he spoke to Olive, he said he would buy the contents of the house if they left the archive. He understood what he stumbled on, that this story wasn’t told, wasn’t talked about and that what he was saving was vital.”

Hidden history to modern museum

When the families left the big houses, everything was auctioned off and scattered. They also, in general, burnt the archives or if they did give them up, it was to the State and many took out the decades of famine.

“They understood,” Caroilin notes, “how it would reflect on most of the families, not all but most, how they treated their tenants at that time.”

For many years, Jim dipped in and out of the archive, with a professional archivist, Martin Fagan, employed only in the last four years. With the archive now catalogued, it’s been made available.

The house opened in 1987 but the vision immediately was to use the archive to tell the story of the famine. To the Callerys, this made perfect sense as “this was the microcosm of what was the macrocosm, of what was happening everywhere else around the country.”

However, not everyone agreed and when the famine museum opened in 1994 there was a lot of criticism on how appropriate the house was as a location.

“We weren’t far from the burnings and dismantling of big houses as that image of British dominance in Ireland. Some of the people that criticised in those early years later admitted that, this is where the story should be told,” says Caroilin.

While operated since 2015 by the Irish Heritage Trust (IHT), the museum itself opened in 1994 and the gardens in 1998. Although the recent renovation has added considerable modernity and comfort to the park Caroilin says: “It’s a never-ending labour of love and philanthropy from my father.”

Famine way

An outreach from Strokestown Park, in partnership with Waterways Ireland, the IHT, Epic Museum and a host of academic institutions, The Famine Way is a trail charting the journey of the 1490 tenants who walked from Strokestown Park to Dublin to the coffin ships that would take them to Canada.

There are 32 pairs of bronze shoes, placed at specific locations where there is a story in relation to the famine. The first pair and the trailhead are at Stokestown Park.

One of the main stories recounted in the famine museum is that of Daniel, who lost all his family bar one little sister. They were adopted by a French Canadian family going on to inherit their farm. His grandson Leo lived with him and heard him tell his story. Jim Callery met Leo, who was then nearly 90, and heard the story.

How close in time this is resonates with Caroilin.

“That was in 2000, not that long ago to be getting first-hand knowledge. The famine isn’t as far back as we think it is and that’s why it’s so embedded in our psyche. We all know about the ships, but what about their last journey on Irish soil?”

In 2015, Caroilin and a group of friends did the walk, as a memorial. As they went through each of the counties, they put out a call for people to join them and were caught by surprise at the number that did and the subsequent media attention.

From that, a conversation arose with Waterways Ireland about turning it into the permanent trail officially launched in 2019.

But it was not history but modern-day geopolitics that was really brought home to Caroilin on this trip.

“On our second day walking in Ballynacarrigy [Westmeath], I got a phone call to tell me that a ship had turned over off the coast of Italy and 600 people had drowned,” she explains.

“That really bothered me because I thought this is what happened to our people. People who were not going to make it, people that were going to find the sea as their grave. I thought, how can this still be happening? How can our past be somebody else’s present?

“We have reached out to work with New Horizons, the emigration group in Athlone. They walked along the trail with us and we have had joint events here. Dad would say: ‘If this is just a museum telling the history, then it’s a dead museum.

“You are duty-bound to use the archive and story to shine a light on what’s happening today in other parts of the world that are similar. Because this isn’t just an old story from our past, this is very much other people’s stories now.”

The unhidden

baron heartlands

Fascinating was the word I kept repeating on my tour from the house, through the equine cathedral to the museum itself. Irish Country Living was guided by expert John O Driscoll, ably assisted by the IHT’s Tony Aspel.

Nicholas Mahon was granted the lands for his services to Cromwell in the late 1600s but it was his grandson, Thomas Mahan, who hired Richard Castles – the German architect who designed Leinster House – to design Strokestown House in the 1740s. For their support of the Act of Union, the family was granted a title – becoming known as the Baron Heartlands of Strokestown.

The first Baron built what is described as the widest street in Ireland. John is very proud to claim that the main street in Strokestown is wider than O’Connell Street, but also admits: “I don’t believe it but I’ve been told I have to accept it.”

Thomas wanted his street to mimic the Champs-Élysées. John asks if I knew that Strokestown is lovingly called the Paris of the west. “No,” I admit, while assuring him I would make sure to communicate this epithet to my readers.

The story of the 1490

The last Baron “Poor Maurice” saw the estate fall into massive debt. On his death, the estate went to his cousin Major Dennis Mahon in 1845. This was where the story of the Strokestown famine walkers begins.

“A debt-ridden estate, the beginning of the great Irish famine, many rent strikes. What was he to do?” John recounts.

“Well, the first thing that happened was wonderful. His daughter Grace Catherine married Henry Sandford Pakenham, the combined lands went up to 30,000 acres at this time and the name changed to Packenham Mahon. On the advice of an agent John Ross Mahon, he began an eviction and immigration scheme to clear his lands. He gathered 1490 men, women and children and had them walk from Strokestown to Dublin along the Royal Canal for ships to Quebec. By the time they got there more than a third of them had died.”

Shortly after, Denis Mahon was assassinated. No member of the family lived at the house after that until Henry Packenham Mahon came to live here and it was his daughter, Olive that sold the estate to Jim Callery.

Read more

Cavan’s hidden heartlands

Building an adventure centre on a farm from the water up

SHARING OPTIONS