“All they need to do is put new packaging on imported meat and they can say it’s Irish”

“Without prejudice to more specific provisions of food law, the labelling, advertising and presentation of food or feed … shall not mislead consumers.”

To ensure that information on packaging is accurate, not misleading and safe, food labelling rules are set out in Irish and EU law. These are mandatory information requirements and must be on the label. Other information which is not required by law is added by the manufacturer or retailer voluntarily.

We asked the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) to clarify a few things for us:

1 Who regulates food labelling in Ireland?

The FSAI is responsible for the enforcement of all pieces of food legislation in Ireland.

This enforcement function is carried out through service contracts with agencies including the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM), Health Service Executive (HSE), Local Authority Veterinary Service (LA) and the Sea Fisheries Protection Authority (SFPA).

How is this policed?

Inspectors from each of these agencies enforce the food labelling rules and provide advice to the food industry. The FSAI co-ordinates this enforcement and also deals directly with regulatory issues and complaints raised by consumers.

Misleading labels (eg the farm name on a product when no such farm exists)

The FSAI acknowledges that information on a food label can at times be confusing or ambiguous and are therefore complaints are dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

2 How many complaints are made each year?

In 2019, 152 complaints were made to the FSAI about labelling (out of a total of 3,359 complaints). The complaints concerned incorrect labelling of allergens, complaints about country of origin labelling on foods, organic foods and labelling not being declared in English.

The FSAI also deals with many queries from the food industry about labelling. Country of origin labelling, allergen labelling, nutrition declaration and nutrition and health claims on foods were the most requested topics.

Legislation sets down specific labelling requirements for nutrition and health claims. There is a list and if the claim is not on this list, it is not permitted to be declared on a label. “Nutrition claim” means any claim which states, suggests or implies that a food has particular beneficial nutritional properties due to the energy and nutrients it provides.

These permitted nutrition claims will manifest most commonly on packaging as claims such as “low”, “reduced”, “free”, “no added”, “high in”, “source of”, “increased”, “light”, and “natural”.

And there is pretty strict criteria to be met before a company can use such claims on pack. Here are two examples:

‘Fat-free’

A claim that a food is fat-free, and any claim likely to have the same meaning for the consumer, may only be made where the product contains no more than 0.5g of fat per 100g or 100ml.

Claims expressed as “X% fat-free” are prohibited.

‘Natural’

Most would take “natural” to mean the product comes from nature and according to the regulations, it actually does have to. This can include:

There is a special dispensation where a product is synonymous with the word “natural”.

For example dairy products such as “natural yoghurt” are manufactured from milk, only using starter cultures necessary for fermentation and are free from other ingredients

The onus is on the food business to ensure that the nutrition or health claim that they intend to use is permitted. It is a complicated business though and does beg the question; is self-regulation better than no regulation?

In part two of this series, we will talk “artisan”, “farmhouse” and “traditional”.

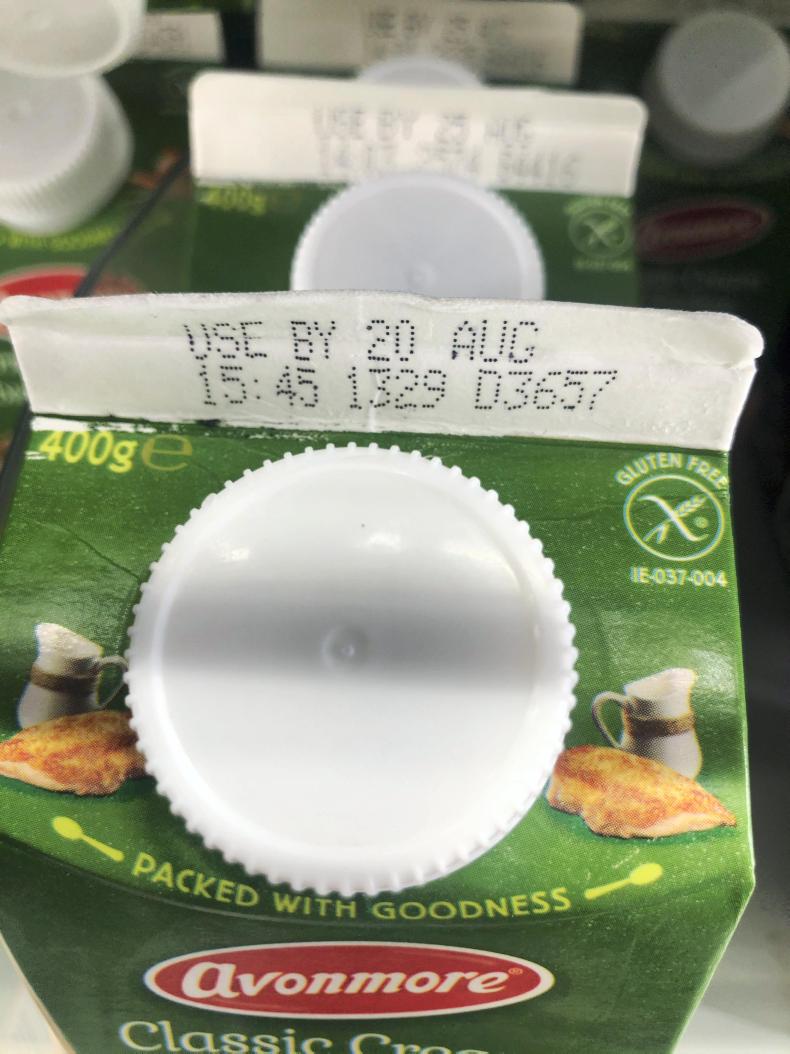

There is a list of mandatory labelling information that is required on the labels of pre-packed foods. In general the following information must be declared on a food label:

Nutrition information (energy, protein, fat etc) is displayed per 100g on the back of packs and sometimes per recommended serving. Safefood recommend using the per 100g column to compare products, but also to look at the recommended portion size as this may be more or less than what you actually eat.

What are traffic lights and are they required?

You will see a traffic lights system on packs (green, amber, red) which are

What is substantial transformation?

This goes to the heart of our original question. The concern that products can be imported, a bit of value added and the product is suddenly Irish.

The EU has specific legislation for customs codes and origin and the determination of originating status is as follows:

In general, “last substantial transformation” is determined in three ways:

Similar to when talking about “natural” and minimum processing, actions which are not considered as substantial include: preservation, sorting, washing, cutting up, changes of packing, assembly, sale, adding marks or labels to packaging or assembly/disassembly.

Under general food labelling rules, the country of origin or place of provenance information need only be labelled where its absence might mislead the consumer, but other rules require the origin for specific foods as follows:

1 Beef labelling (Reg 1760/2000) requires the origin of beef to be declared

Such labelling has been required for fresh beef and beef products since January 2002, as a consequence of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) crisis. The label has to indicate the place of birth, rearing and slaughter.

2 Regulation (EU) No 1337/2013 requires the origin of meat from pigs, goats, sheep and poultry to be on labels for consumers

If the meat does not originate in one single country, the indications required are:

3 Primary ingredient of a final food: (Reg 2018/775) requires the origin of a primary ingredient to be declared on the label

For example, where the origin of a chicken curry is declared as Irish on the label but the chicken is not Irish, then it will be a legal requirement to also give the origin of the chicken on the label.

The cardinal rule is that food businesses cannot “mislead the consumer” and the legislation is in place - so much, you could find yourself buried in it. But even the authorities will admit that it is ambiguous so we need to continue to “watch this space”.

Send us your questions and we will endeavour to get answers.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: