I want to teach women to play chess.” I looked at Dr Monica Gorman, quizzically; “Go on, explain”. Of course, she didn’t mean the physical act of playing chess. She meant that she wanted women to be more strategic.

Monica is a lecturer in agricultural extension and innovation in UCD’s School of Agriculture and Food Science. She completed a PhD examining the prospects for expanding livelihood opportunities for farm families in 2004 but her interest in gender equality stems from her youth and time spent in Africa, as well as her research.

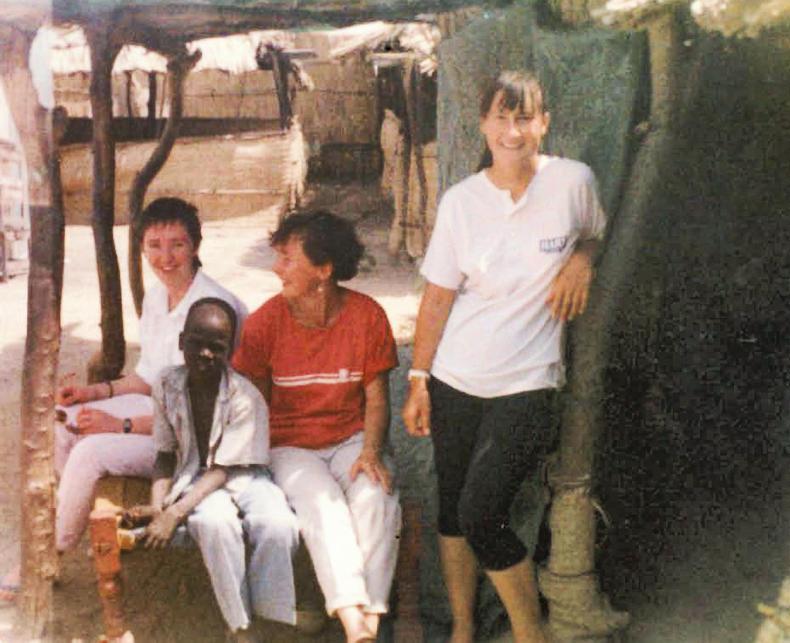

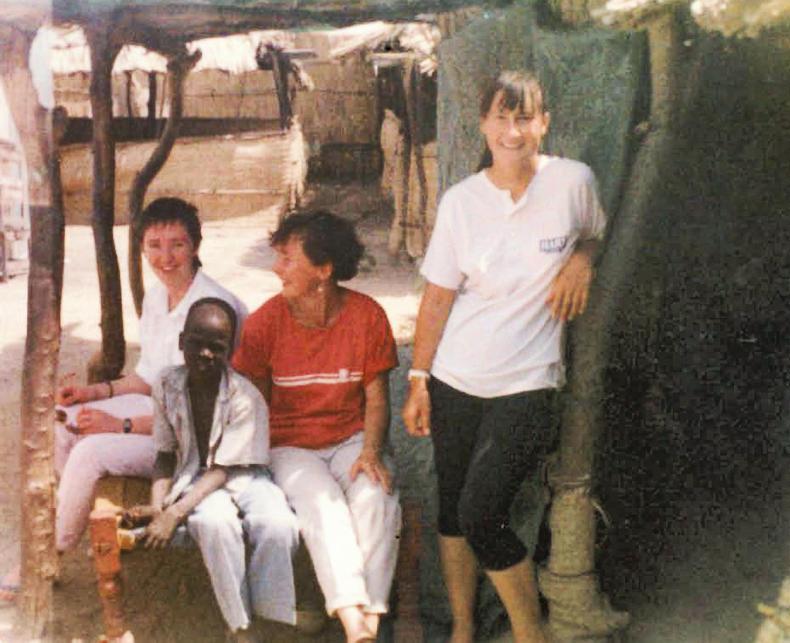

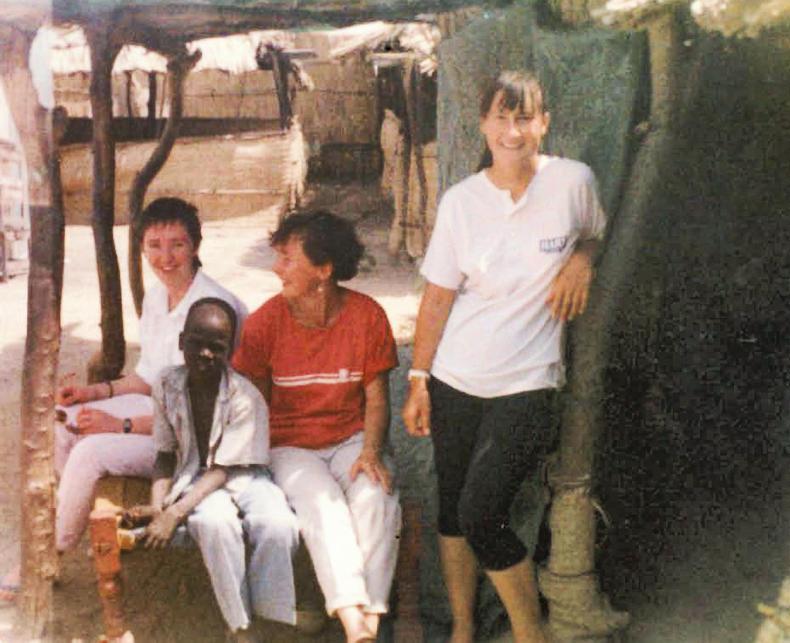

Monica Gorman with teachers and students in the Shagarab refugee camp in eastern Sudan in 1989.

That research has shown that, within Irish farm families, there are opportunities to improve livelihood outcomes if women are more actively involved.

Looking at dynamics in farm households, she found that where the wife had a role in farm decisions and was an official partner – outcomes were more positive.

“It is common in Ireland that women are invisible, their voices not acknowledged, even though they might be playing a pivotal role in the farm business.”

The African experience

In the 1980s, Monica worked with semi-nomadic pastoralists in Sudan with Concern.

“I was living in a remote area where young girls were often married off at 13 or 14 to 60-year-old men who owned large herds of livestock. This really got me thinking about the power dynamics that keep women “in their place”.

“When I worked with Irish aid in Tanzania, it was on a broader rural development project.

“Most people depended on subsistence agriculture and we did a lot of work with rural women. Women would pay back loans, were more conscientious and took less risks than men. If they had access to more resources they really made a substantive difference to communities.

This time in Africa and seeing these dynamics made me think about gender and control. I started to look at the more strategic needs that might challenge the balance of power.

Power dynamics

Monica came from a farm in Wicklow – dairy on 77 acres. It was her mother who inherited the farm and her father who married in, having come to the area working on rural electrification.

“My mother did farm accounts and worked for ifac. She was adamant on how important education was. The mother-daughter dynamic has a huge impact. If a mother dissuades her daughter from a career choice by saying things like, ‘veterinary is an awful hard career for a woman’ what the daughter hears is, ‘you are not good enough’. These comments can come from a place of care and love, but they can feed fear instead of confidence.

Monica Gorman in the orchard in Sheepwalk, Arklow.

“A young woman’s norms are modelled on what she sees, so a girl’s relationship with both parents is important. It can be complex and there will always be a level of tension between parents and their children but that first role modelling, which is just as important for sons, will form a basis for the future.

Interaction with a teacher who went overseas with Concern and an aunt (now 90) who worked in Africa in the 1960s and 70s inspired Monica to travel and believe that you could go anywhere or do anything, even though she also inherited a lot of traditional norms.

“I have one brother and two sisters. If I was milking the cows, I still had to wash dishes, but my brother didn’t and that brought a sense of frustration. There were other times when I had to put my head above the parapet. When running to become auditor of AgSoc (the UCD Agricultural Science Society committee chair), a girl said to me, ‘I just couldn’t vote for a woman’. I was flabbergasted by this lack of support from another women. The underlying current was that you should get back in your box. The implication was ‘you are being too brazen’.”

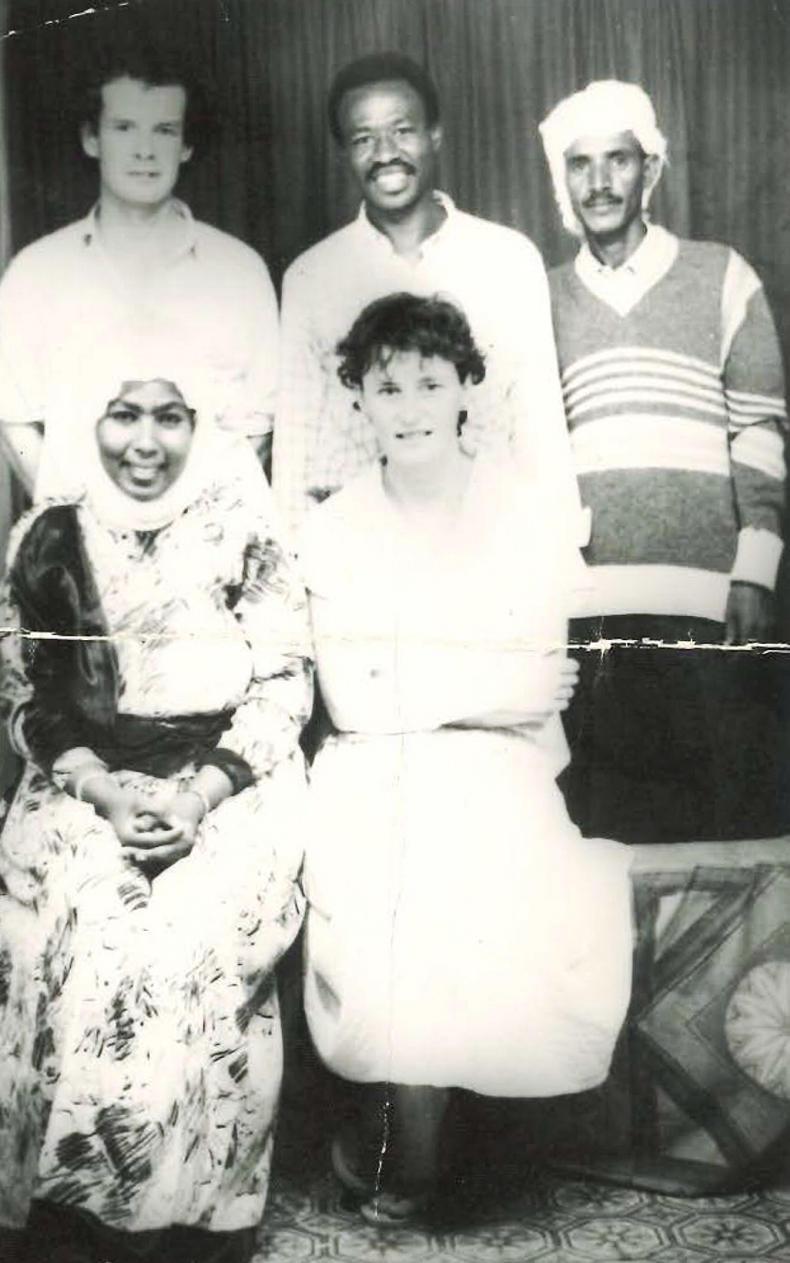

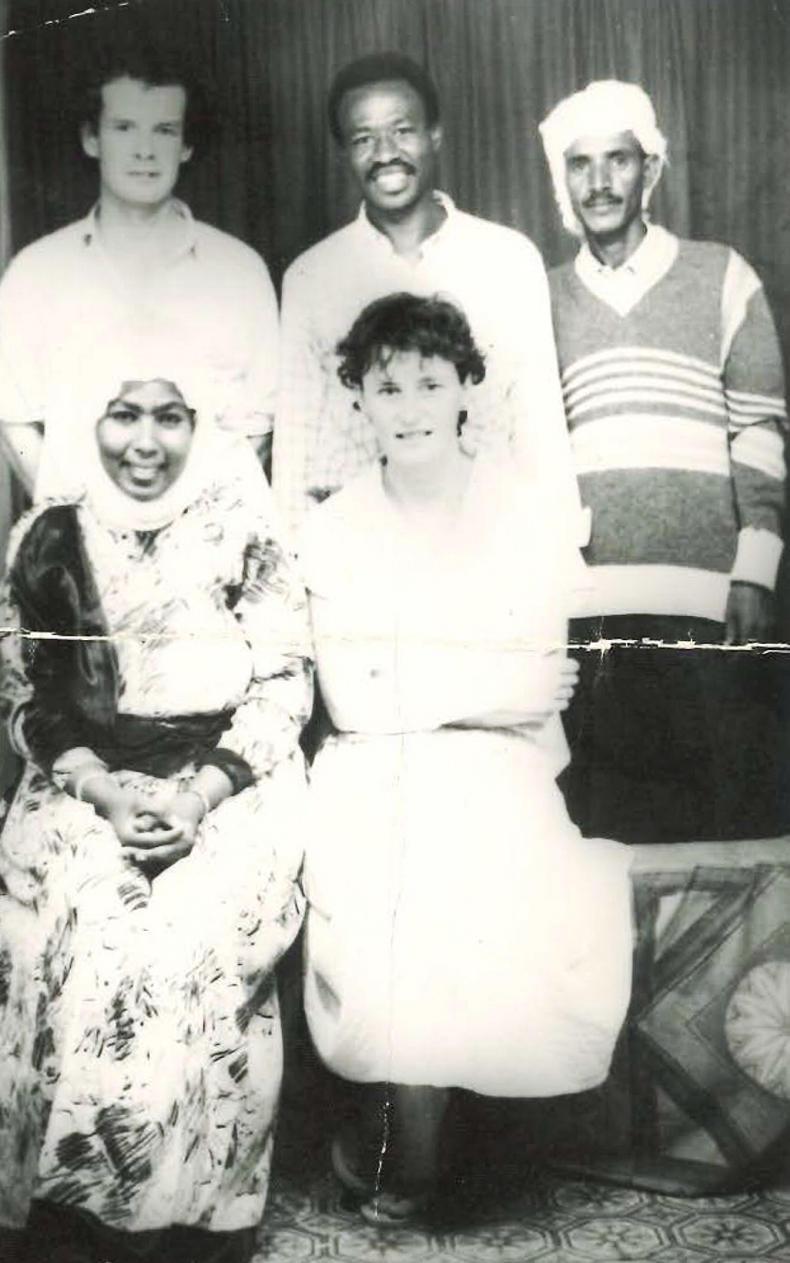

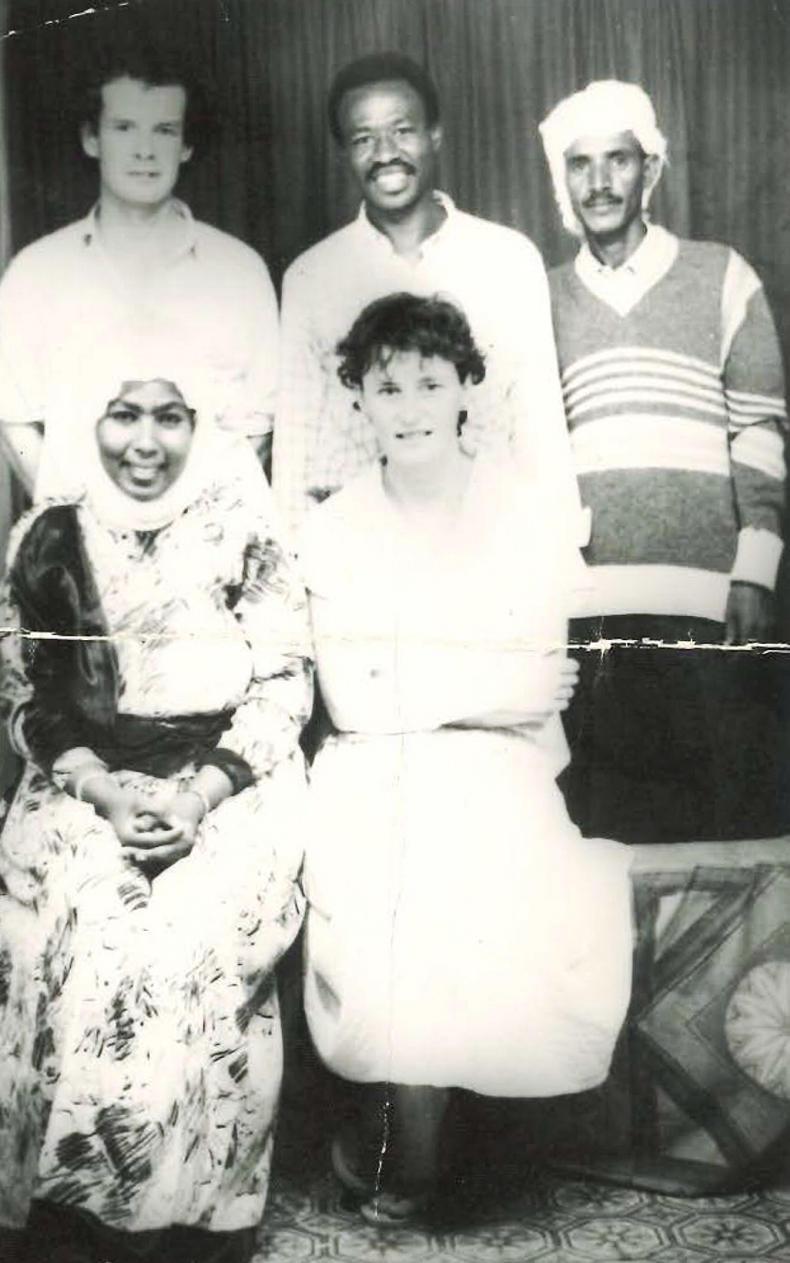

Monica Gorman and Concern staff in Shagarab, eastern Sudan, in 1989.

But elected she was, becoming the second female auditor. She was the first women to invite the president of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA), Ina Broughall, to a conference. It was on the future of the family farm in Ireland and to Monica it made sense to have her present.

“When I was doing my masters I started to look at why gender matters in rural development. For a lot of women, they are aware that there is something wrong in the system. Sometimes going away makes it easier to see things in a new light.”

In Tanzania, Monica attended a national conference on agricultural extension.

As everything had to go through the chief, this harassment was part and parcel of getting anything done

The keynote speaker, a woman, addressed the issue of sexual harassment from the chief of the village and the vulnerability that this brought.

“As everything had to go through the chief, this harassment was part and parcel of getting anything done. This kind of dependency or powerlessness is a problem for women, not just in Africa but here in Ireland also.”

People in power

“Dependency and powerlessness are linked and when a woman is disempowered, it is hard to change things. With any relationship, there is a contract and within that contract we can feel that we are dependent, interdependent or independent.

“With a dependant relationship, I stay at home and I am dependent on X and often what I do or contribute to the relationship is not valued or respected.

“Independence is more a relationship of two halves, where you do your thing and I do mine and what holds us together is our feelings for each other and perhaps our home and children.

“An example of an interdependent relationship is when a couple, who are farming together, one may take more responsibility for childcare, the other for the farm work but they know they are in it together and they need each other. The work and contribution of each is respected as equal.

“The latter is so often not the case with women’s work frequently not valued.”

Irish Country Living questions what can someone do if they find themselves in a position where the power dynamic is swung out of their favour?

An explicit contract

“The power dynamic often swings when there are young children and a woman has put her career on hold to look after the family. Her work can become invisible, taken for granted and she can easily feel dependent.

“I have a friend who made an explicit agreement with her husband when she went on maternity leave that he would pay her a weekly income from his salary so she would not have to ask for money or feel dependent.

“There was a psychology to this, a contract. Taking maternity leave was not to be taken for granted. The contract was ‘we are in this together’.”

Mutual support

“There is an awful lot to be said for the mutual support that women give each other.

“I will be honest I didn’t really want to do this panel [CERES breakfast briefing – see panel] but it’s not an option to sit back. You owe it to other women to go forward, you simply can’t opt out.

We need to talk about the contribution of women

“Nothing will change if we are not part of the change. Men want change as well but we need to engage.

“We need to talk about the contribution of women and we need to teach women how to play chess – women tend to play the immediate move whereas we need to think three steps ahead.

“We should always be thinking strategically, whether that is your pension plan or your next career move. You can still work selflessly while thinking strategically.

“Women are more likely to be exploited as they take on too much responsibility at times. We need to recognise this. Yes, you can do it but you need to do it in a way that you treat people right and you are being treated right. You need to recognise and ask yourself ‘what is going on here?’ We need to encourage each other and building up women’s confidence is vital.”

Confidence to have ‘that’ conversation

“You may love your husband or partner but often within farms he is part of something that is not just him. There is his relationship with the farm, your relationship with your own life and career and then there is the relationship between the two of you.

It will depend on what the relationship is like with the parents and siblings

Marrying into a farm can bring its own set of complications. It will depend on what the relationship is like with the parents and siblings and how much room there is to have independent lives from others with an interest in that farm business.

“To have the honest and sometimes difficult conversation, you need confidence. And thereafter you need to be confident in how you manage those relationships.”

Education

“Education is key as if you don’t own and control resources you are powerless. Education gives you confidence and opens opportunities to become financially secure and freedom to be independent.

“If you feel trapped and see no options, do a course. This doesn’t need to be formal education.

“A part-time course that gets you out of the house meeting people will give a sense of empowerment. It could be a chainsaw course or artificial insemination to give you more skills on the farm.

Who you meet is what is important here

“Or do something for yourself like art or creative writing. Who you meet is what is important here. Keeping in contact with people that are positive as they will help you see you have options.”

Monica will join Sinead McPhillips, assistant secretary general, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, and John Jordan, CEO of Ornua in a panel discussion addressing the topic of ‘Striking the gender balance in Irish Agri-food’ in the Killashee House Hotel on Tuesday 25 February 2020 starting at 7am, organised by the CEREK Network.

You can register for this event at ceresnet.ie

I want to teach women to play chess.” I looked at Dr Monica Gorman, quizzically; “Go on, explain”. Of course, she didn’t mean the physical act of playing chess. She meant that she wanted women to be more strategic.

Monica is a lecturer in agricultural extension and innovation in UCD’s School of Agriculture and Food Science. She completed a PhD examining the prospects for expanding livelihood opportunities for farm families in 2004 but her interest in gender equality stems from her youth and time spent in Africa, as well as her research.

Monica Gorman with teachers and students in the Shagarab refugee camp in eastern Sudan in 1989.

That research has shown that, within Irish farm families, there are opportunities to improve livelihood outcomes if women are more actively involved.

Looking at dynamics in farm households, she found that where the wife had a role in farm decisions and was an official partner – outcomes were more positive.

“It is common in Ireland that women are invisible, their voices not acknowledged, even though they might be playing a pivotal role in the farm business.”

The African experience

In the 1980s, Monica worked with semi-nomadic pastoralists in Sudan with Concern.

“I was living in a remote area where young girls were often married off at 13 or 14 to 60-year-old men who owned large herds of livestock. This really got me thinking about the power dynamics that keep women “in their place”.

“When I worked with Irish aid in Tanzania, it was on a broader rural development project.

“Most people depended on subsistence agriculture and we did a lot of work with rural women. Women would pay back loans, were more conscientious and took less risks than men. If they had access to more resources they really made a substantive difference to communities.

This time in Africa and seeing these dynamics made me think about gender and control. I started to look at the more strategic needs that might challenge the balance of power.

Power dynamics

Monica came from a farm in Wicklow – dairy on 77 acres. It was her mother who inherited the farm and her father who married in, having come to the area working on rural electrification.

“My mother did farm accounts and worked for ifac. She was adamant on how important education was. The mother-daughter dynamic has a huge impact. If a mother dissuades her daughter from a career choice by saying things like, ‘veterinary is an awful hard career for a woman’ what the daughter hears is, ‘you are not good enough’. These comments can come from a place of care and love, but they can feed fear instead of confidence.

Monica Gorman in the orchard in Sheepwalk, Arklow.

“A young woman’s norms are modelled on what she sees, so a girl’s relationship with both parents is important. It can be complex and there will always be a level of tension between parents and their children but that first role modelling, which is just as important for sons, will form a basis for the future.

Interaction with a teacher who went overseas with Concern and an aunt (now 90) who worked in Africa in the 1960s and 70s inspired Monica to travel and believe that you could go anywhere or do anything, even though she also inherited a lot of traditional norms.

“I have one brother and two sisters. If I was milking the cows, I still had to wash dishes, but my brother didn’t and that brought a sense of frustration. There were other times when I had to put my head above the parapet. When running to become auditor of AgSoc (the UCD Agricultural Science Society committee chair), a girl said to me, ‘I just couldn’t vote for a woman’. I was flabbergasted by this lack of support from another women. The underlying current was that you should get back in your box. The implication was ‘you are being too brazen’.”

Monica Gorman and Concern staff in Shagarab, eastern Sudan, in 1989.

But elected she was, becoming the second female auditor. She was the first women to invite the president of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA), Ina Broughall, to a conference. It was on the future of the family farm in Ireland and to Monica it made sense to have her present.

“When I was doing my masters I started to look at why gender matters in rural development. For a lot of women, they are aware that there is something wrong in the system. Sometimes going away makes it easier to see things in a new light.”

In Tanzania, Monica attended a national conference on agricultural extension.

As everything had to go through the chief, this harassment was part and parcel of getting anything done

The keynote speaker, a woman, addressed the issue of sexual harassment from the chief of the village and the vulnerability that this brought.

“As everything had to go through the chief, this harassment was part and parcel of getting anything done. This kind of dependency or powerlessness is a problem for women, not just in Africa but here in Ireland also.”

People in power

“Dependency and powerlessness are linked and when a woman is disempowered, it is hard to change things. With any relationship, there is a contract and within that contract we can feel that we are dependent, interdependent or independent.

“With a dependant relationship, I stay at home and I am dependent on X and often what I do or contribute to the relationship is not valued or respected.

“Independence is more a relationship of two halves, where you do your thing and I do mine and what holds us together is our feelings for each other and perhaps our home and children.

“An example of an interdependent relationship is when a couple, who are farming together, one may take more responsibility for childcare, the other for the farm work but they know they are in it together and they need each other. The work and contribution of each is respected as equal.

“The latter is so often not the case with women’s work frequently not valued.”

Irish Country Living questions what can someone do if they find themselves in a position where the power dynamic is swung out of their favour?

An explicit contract

“The power dynamic often swings when there are young children and a woman has put her career on hold to look after the family. Her work can become invisible, taken for granted and she can easily feel dependent.

“I have a friend who made an explicit agreement with her husband when she went on maternity leave that he would pay her a weekly income from his salary so she would not have to ask for money or feel dependent.

“There was a psychology to this, a contract. Taking maternity leave was not to be taken for granted. The contract was ‘we are in this together’.”

Mutual support

“There is an awful lot to be said for the mutual support that women give each other.

“I will be honest I didn’t really want to do this panel [CERES breakfast briefing – see panel] but it’s not an option to sit back. You owe it to other women to go forward, you simply can’t opt out.

We need to talk about the contribution of women

“Nothing will change if we are not part of the change. Men want change as well but we need to engage.

“We need to talk about the contribution of women and we need to teach women how to play chess – women tend to play the immediate move whereas we need to think three steps ahead.

“We should always be thinking strategically, whether that is your pension plan or your next career move. You can still work selflessly while thinking strategically.

“Women are more likely to be exploited as they take on too much responsibility at times. We need to recognise this. Yes, you can do it but you need to do it in a way that you treat people right and you are being treated right. You need to recognise and ask yourself ‘what is going on here?’ We need to encourage each other and building up women’s confidence is vital.”

Confidence to have ‘that’ conversation

“You may love your husband or partner but often within farms he is part of something that is not just him. There is his relationship with the farm, your relationship with your own life and career and then there is the relationship between the two of you.

It will depend on what the relationship is like with the parents and siblings

Marrying into a farm can bring its own set of complications. It will depend on what the relationship is like with the parents and siblings and how much room there is to have independent lives from others with an interest in that farm business.

“To have the honest and sometimes difficult conversation, you need confidence. And thereafter you need to be confident in how you manage those relationships.”

Education

“Education is key as if you don’t own and control resources you are powerless. Education gives you confidence and opens opportunities to become financially secure and freedom to be independent.

“If you feel trapped and see no options, do a course. This doesn’t need to be formal education.

“A part-time course that gets you out of the house meeting people will give a sense of empowerment. It could be a chainsaw course or artificial insemination to give you more skills on the farm.

Who you meet is what is important here

“Or do something for yourself like art or creative writing. Who you meet is what is important here. Keeping in contact with people that are positive as they will help you see you have options.”

Monica will join Sinead McPhillips, assistant secretary general, Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, and John Jordan, CEO of Ornua in a panel discussion addressing the topic of ‘Striking the gender balance in Irish Agri-food’ in the Killashee House Hotel on Tuesday 25 February 2020 starting at 7am, organised by the CEREK Network.

You can register for this event at ceresnet.ie

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: