The recent increase in optimism in the sheep sector is thankfully getting more young people involved, while there are also farmers converting to sheep or possibly returning to lambing ewes after a period of time.

In the recent Irish Farmers Journal reader survey, a request which arose on a number of occasions was getting back to basics and covering some beginners or refresher-type article.

With lambing ramping up, it is perfect timing to include our first refresher topic on lambing the ewe.

Under normal conditions, a high percentage of ewes generally lamb unassisted. But there are always times where lambs may be presented incorrectly in the birth canal and require assistance or where the ewe may need help in delivering oversized lambs.

This article deals with the many ways in which malpresentations occur, but before delving into this issue, it is important to know when it is time to intervene in potential problems.

Signs of lambing

In the hours before lambing, a ewe will become uneasy or show signs of sickness.

The signs can vary, depending on whether ewes remain outdoors or are housed.

Where lambing outdoors, ewes will tend to separate from the flock. This is especially true of hill and mountain breeds, where their natural instinct is to find a safe sheltered place to lamb.

Ewes lambing indoors often tend to take a similar approach of separating from the flock, but this is harder to detect.

Another indication is ewes failing to come to eat or continually standing and lying or bleating looking for lambs.

Where lambs are present in the same pen, ewes may think other lambs are her own, so she will try to mis-mother these.

For this reason, it is advantageous to remove ewes and lambs as soon as possible to individual lambing pens for a period to develop a strong bond.

In some cases, early signs of labour may be shown two to three hours before lambing actually takes place

During this period, contractions may have started. A lamb is surrounded by two fluid-filled sacks, normally known in practical terms as the first and second water bag.

Frequent contractions will push the first water bag into the cervix, causing its dilation (to make room for the lamb to pass through).

If a ewe is handled too early, this may not have taken place or the lamb may not yet have progressed into the birth canal.

Danger of causing harm

In these circumstances, there is a danger of causing harm to the ewe and the lamb by trying to bring lamb(s) too soon.

This process may take place quickly, but, in some cases, early signs of labour may be shown two to three hours before lambing actually takes place.

It is sometimes hastened by another ewe in the pen lambing.

In addition to lying and standing regularly, ewes may be seen pawing the ground with their front feet.

If the length of time a ewe is lambing is not known and you think there may be problems, it is advisable to handle the ewe to see if everything is OK.

If the birth is progressing normally, the ewe can be left for longer to lamb herself or the lambs can be brought if it is possible to do so.

A sure sign that a lambing is progressing successfully is the hooves of the two legs and a lamb’s nose appearing in the second water bag.

Lambing from expulsion of the first water bag should generally take less than an hour or slightly over it for multiple births.

Dealing with lambing difficulties

The diagrams below will hopefully help you to visualise the different problems that can occur and how these can be rectified.

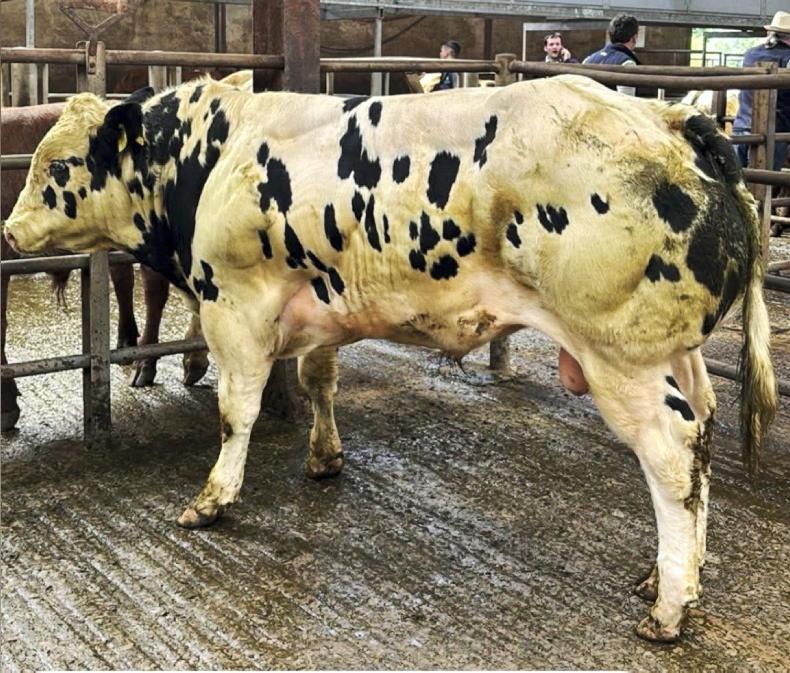

Oversized lamb

Even though the lamb may be presented in the correct manner, a difficult birth may take place due to oversized lambs or a small ewe/ewe lamb. Using plenty of lubricant will help.

The legs of the lamb should be pulled gently, one at a time, to carefully ease the lamb further out.

Care should be taken when bringing the lamb not to rupture or cause any tears to the vulva of the ewe.

When the lamb is coming, the skin of the vulva may need to be pulled gently back over the head, which should make it easier to bring the lamb.

The force applied should be steady and not jerked. The force should be applied above the hocks (bend in leg) and behind the lamb's ears by using a lambing aid.

Pull the lamb towards the ewe's hocks. If the lamb gets stuck, turning the ewe on her back may help.

If the lamb is stuck at the hips, releasing pressure and then pulling the lamb between the ewe's legs and over the udder frequently helps.

Continuous pressure in one direction where a lamb is stuck at the hips generally does not work.

It is important to use your judgement at the start, as if the lamb is too large, veterinary assistance should be sought, as a caesarean section may be necessary.

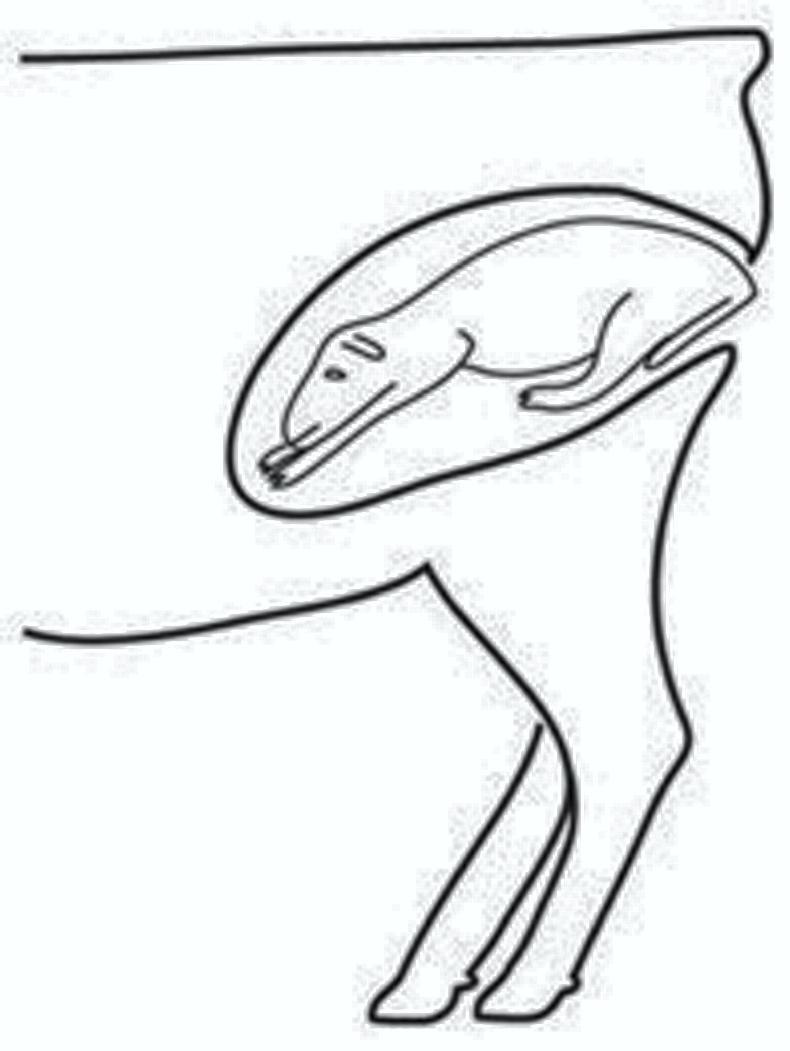

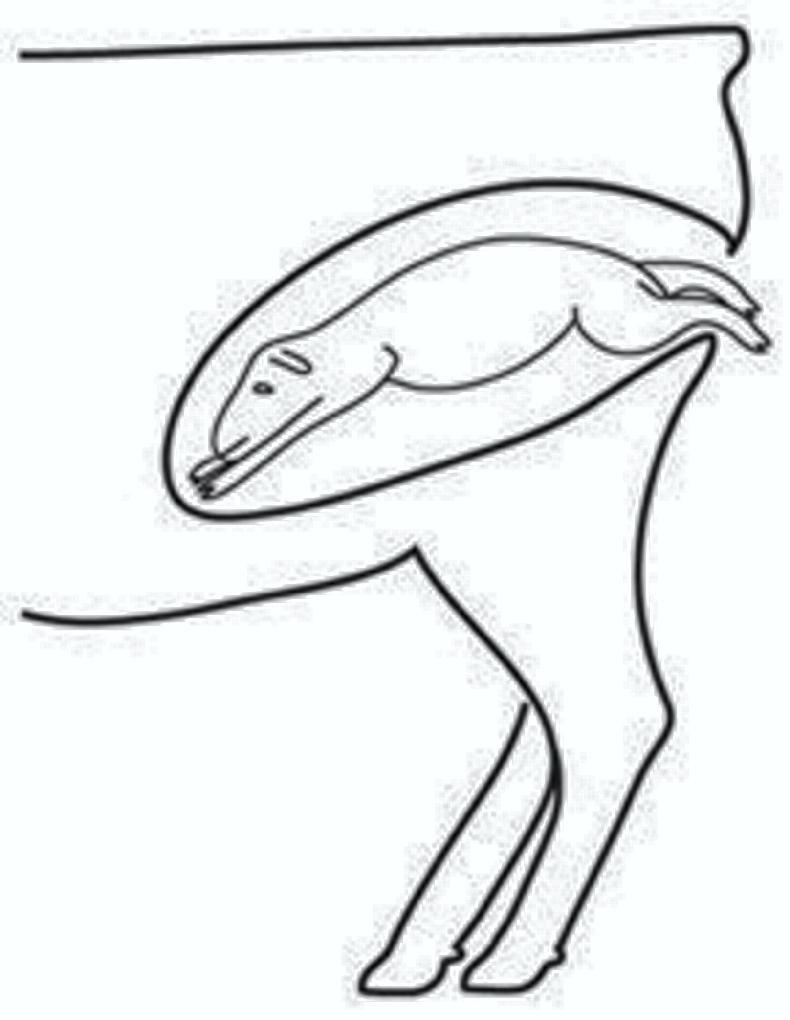

Normal lambing

Normal lambing.

In a normal lambing, the two front legs of the lamb will be extended, with the head coming in between them.

The tips of the legs and head may be seen for a significant time before the birth takes place, but once the ewe has pushed the heads and shoulders out, the lamb will generally be delivered rapidly.

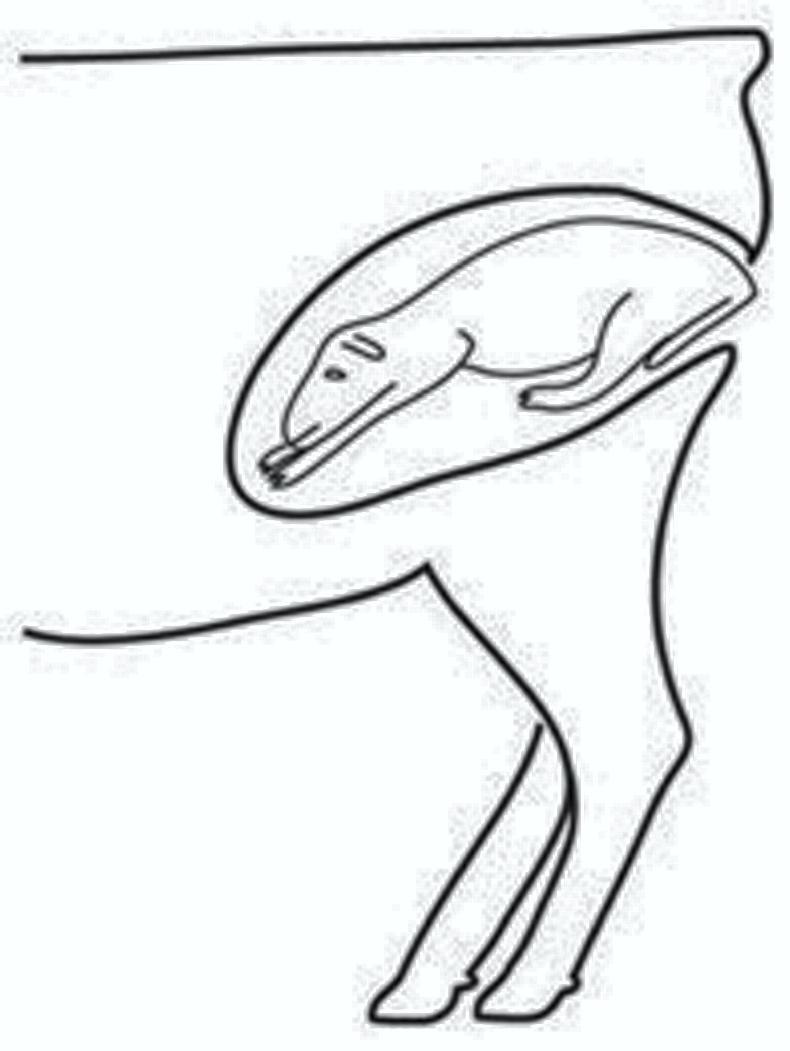

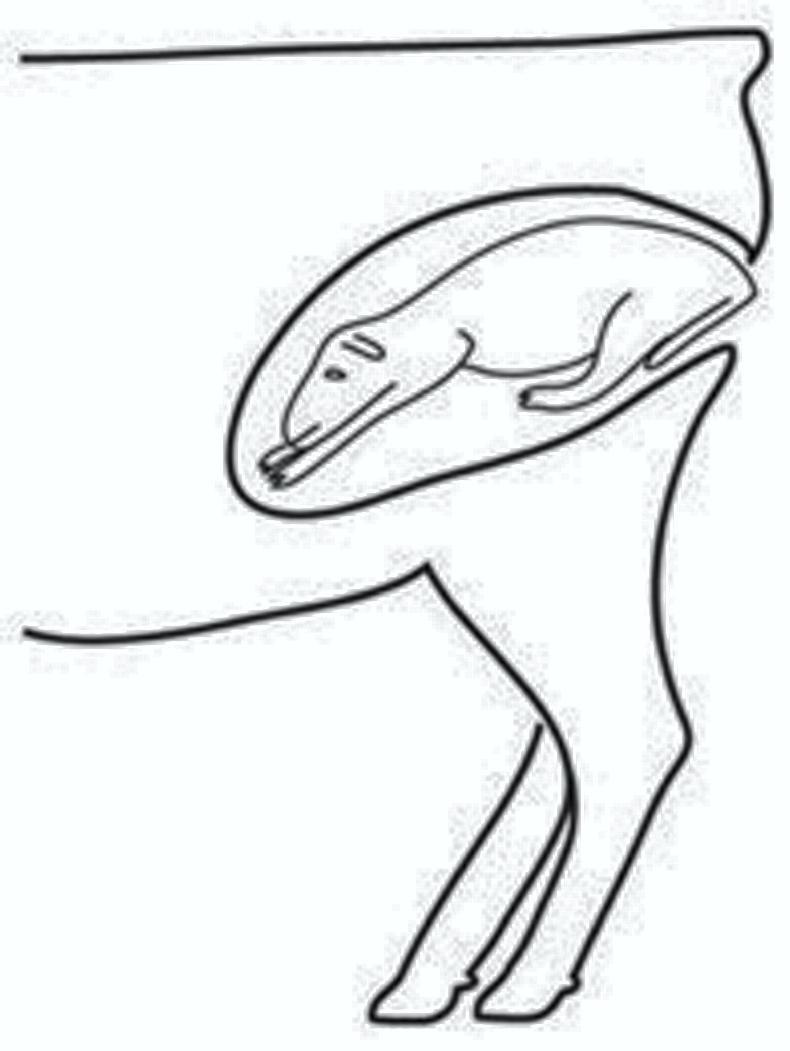

Head but no legs

Two legs but no head.

This type of malpresentation is very serious. If not noticed quickly, the lamb's head can swell fast, with the tongue also swelling as time passes.

In this situation, the head needs to be re-inserted into the birth canal, as there is generally no room to bring the legs out.

Lubricant should be used to help get the head back into the ewe.

Before reinserting, clean any foreign material, such as straw or dirt, from the head to minimise the risk of infection.

A lamb born in this situation will need careful attention and more than likely stomach tubing, as normal sucking behaviour will usually be compromised.

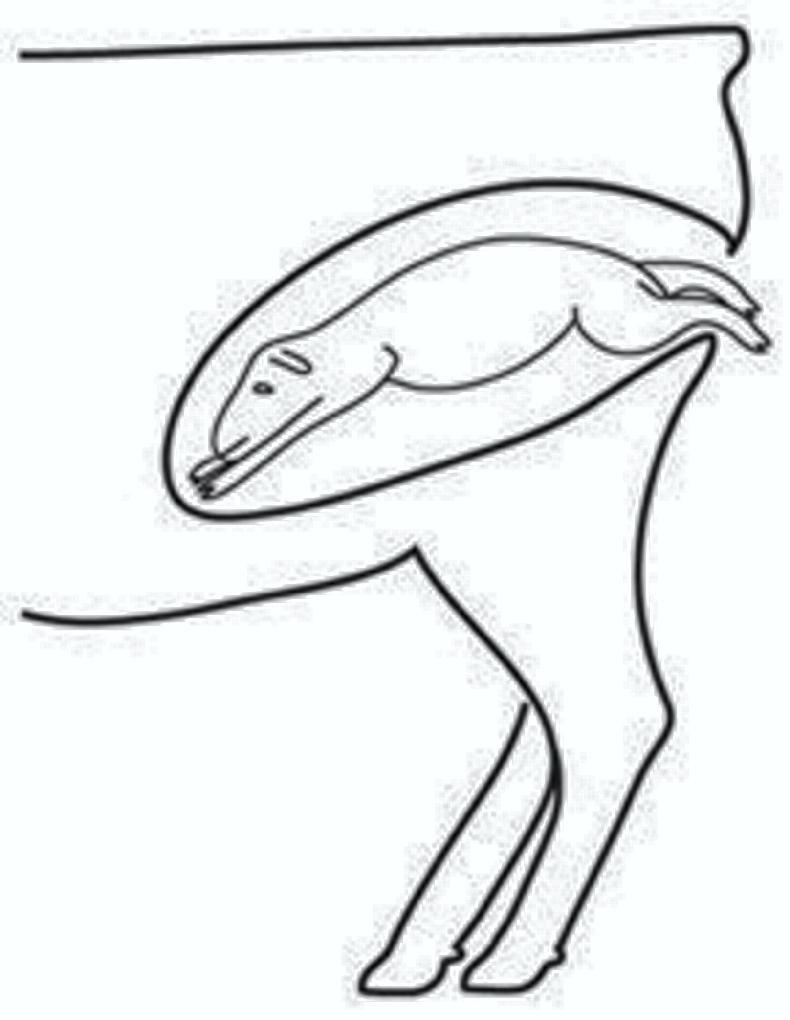

Head and one leg

Head and one leg.

This is similar to a head and no legs, but just not quite as serious.

Where possible, try to bring the other leg before delivering the lamb.

If there is plenty of room, it may just be a case of turning the leg upward.

If this is not possible, it will require reinserting the leg and head into the birth canal.

Use a lambing cord or aid to keep the head in the right position if you think it may fall back out of place.

In some cases where the lamb is small, especially with multiple births, it may be possible to bring the lamb with one leg and the head.

The head should again be gripped behind the ears and not the mouth or jaw.

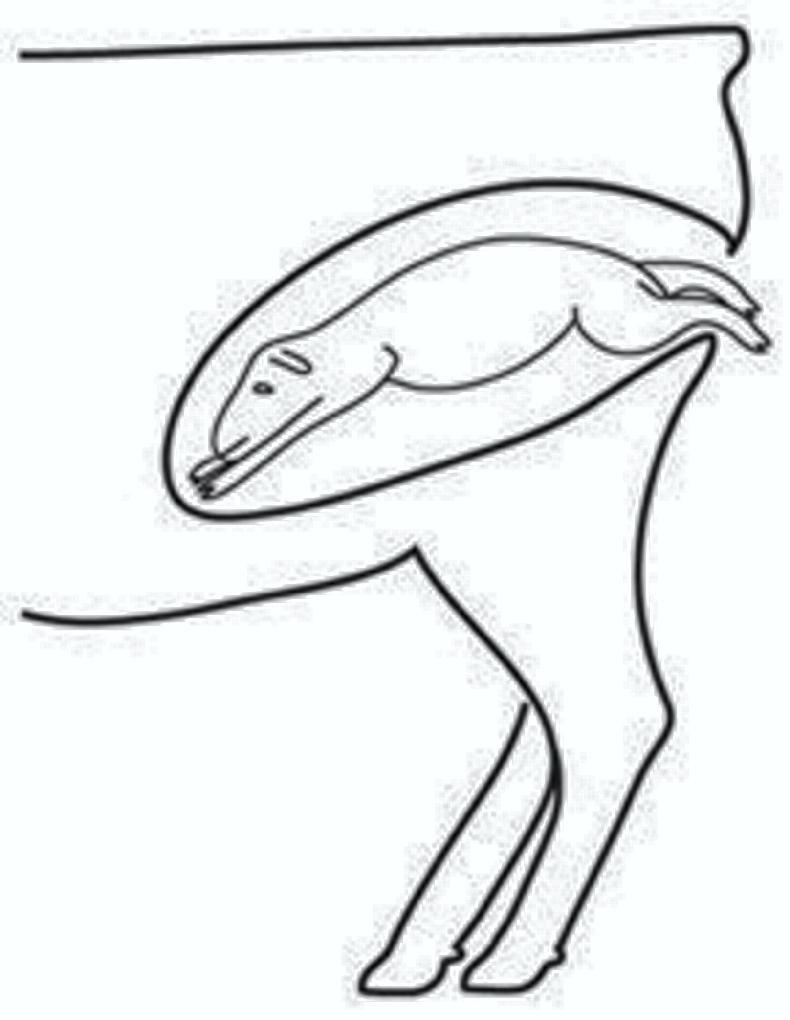

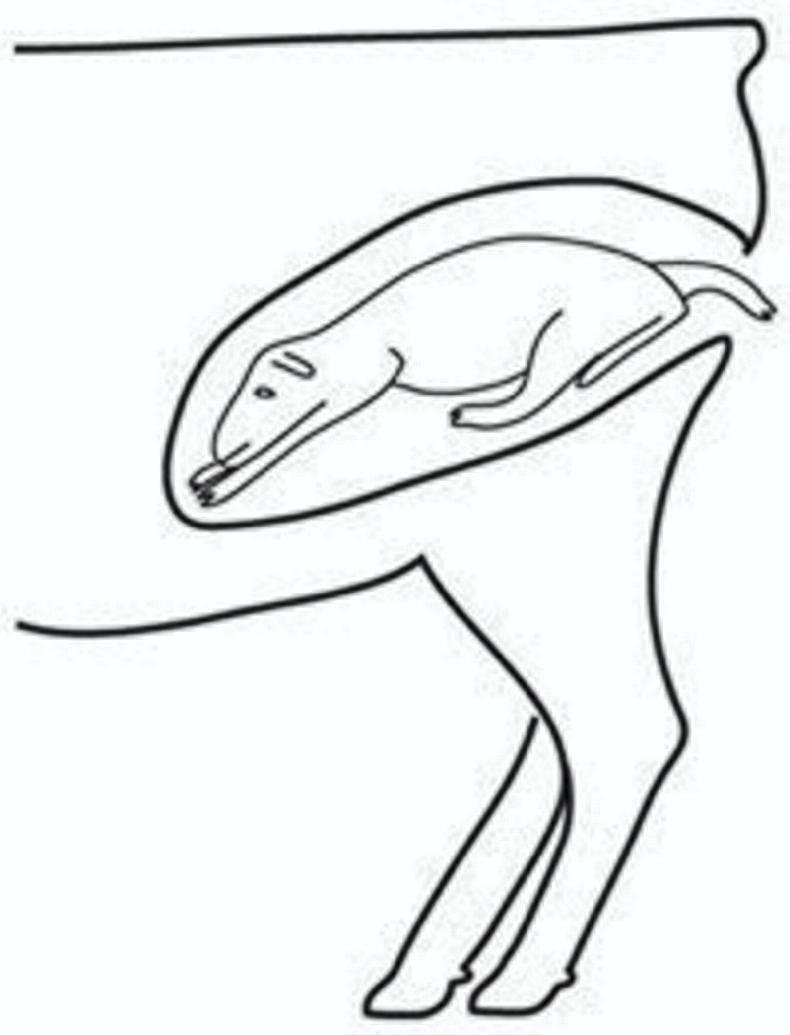

Two legs but no head

Two legs but no head.

This can be tricky, as when a lamb's head has gone back, it is generally difficult to get the head and legs lining up correct again.

A lambing aid or a lambing cord, which can essentially be a piece of washing line, for example, can be used to grip the lamb's head.

Again, catch behind the ears and loop over the head.

The head can be brought forward with the cord, while the legs can be brought with the other hand.

Pull the head and the legs gradually into the birth canal, where the lamb may be oversized or the birth canal is tight.

Two lambs at once

Two lambs at once.

A malpresentation involving multiple lambs requires patience and visualisation of what way the lambs are fixed inside the ewe.

Try to locate the two legs and the head of the same lamb and then see if the lamb can be brought.

Again, it may require the use of a lambing aid to guide the head or legs forward.

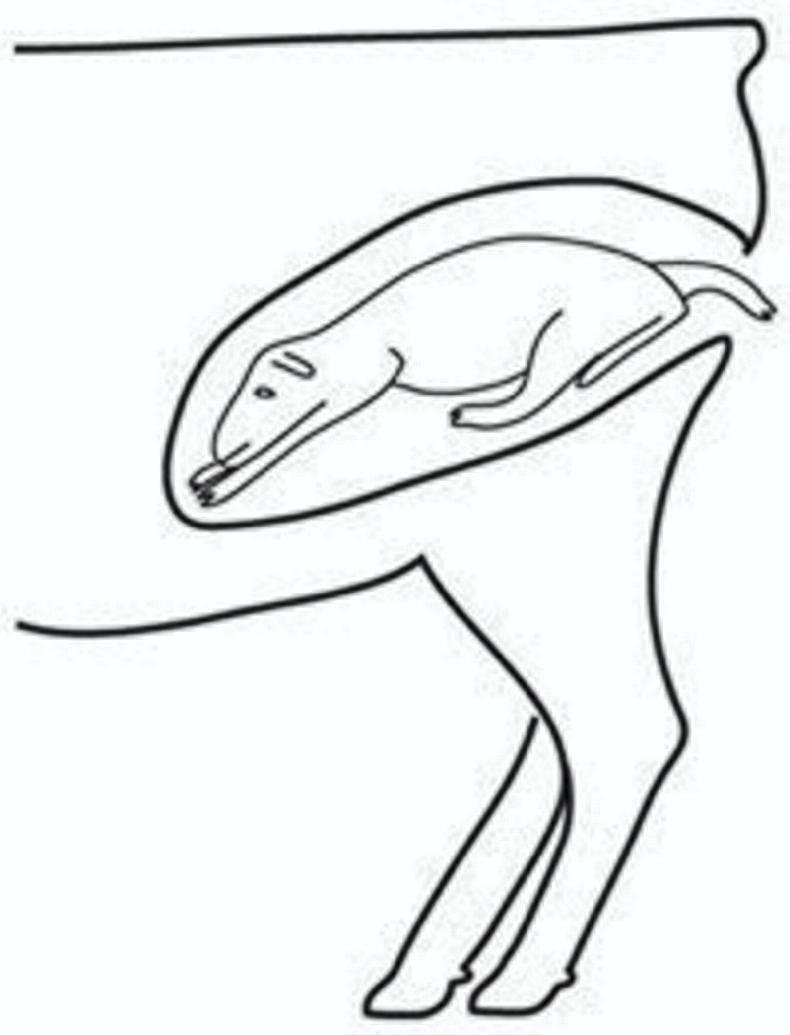

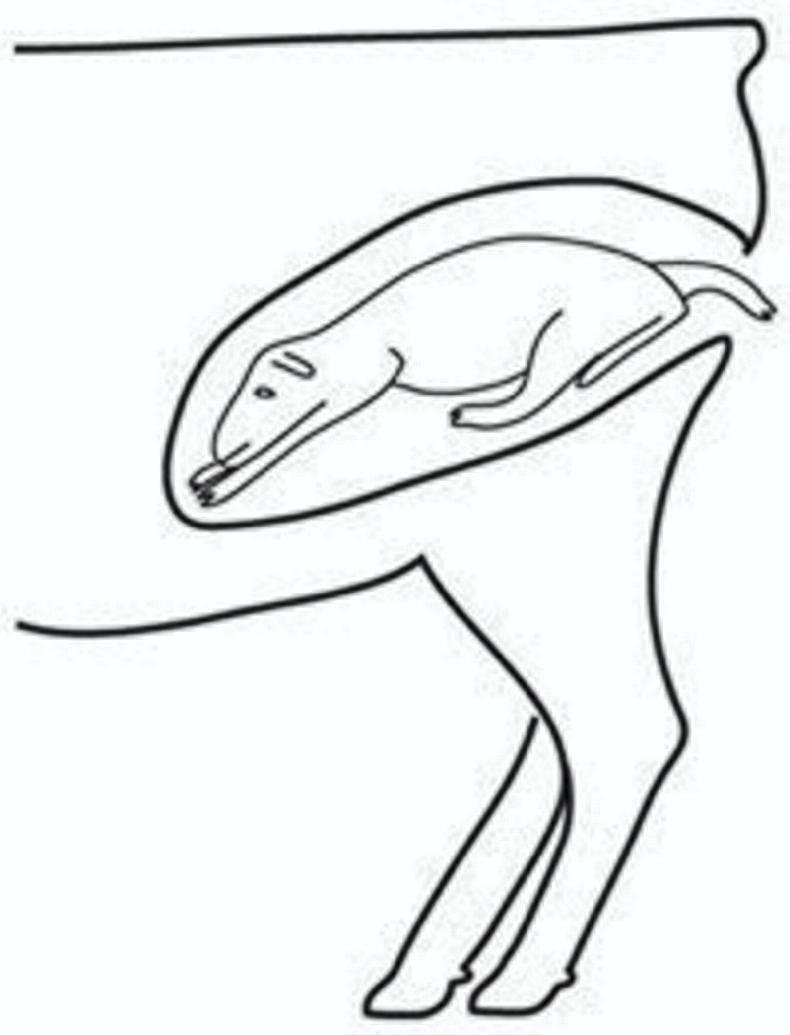

Lamb backwards - two legs back

Lamb backwards - two legs back.

This is also known as breech presentation, with both legs back and situated neatly under the lamb.

It is generally best to deliver the lamb in the position it is in, rather than trying to turn the lamb in the uterus.

Doing so increases the risk of breaking the umbilical cord and drowning the lamb.

Raise the tail firstly and then try to raise the back legs into the birth canal one at a time.

Grabbing the leg at the fetlock (turn of leg) is generally best, then raising the leg into the birth canal.

This may require pushing the lamb back towards the uterus to have more room to work.

Lamb backwards - two legs coming

Lamb backwards- two legs coming.

This situation is usually relatively easy to overcome, as long as the lamb is not over-sized.

Bring the lamb backwards as quick as possible. Delaying delivery once you have started to assist the birth may result in the umbilical cord breaking and the lamb drowning in fluid.

Lamb backwards - one leg back

Lamb backwards - one leg down and one leg coming.

This is very similar to two legs coming backwards.

Raise the second leg, which generally requires pushing the lamb back towards the uterus to make room to raise the leg.

Deliver as advised above.

Dealing with the newborn lamb

Once a lamb has been delivered, deal with it to ensure it is OK.

If a lamb is showing little sign of life, holding it upside down by the legs and swinging it gently in a 180-degree arc may help to clear the lungs of any fluids.

Only do this for a short period of a few swings.

Rubbing the lamb's ribs may also help. Also wipe any mucus from around the mouth and ears.

Where a lamb appears to be having problems breathing, a piece of straw can be inserted gently into its nose to help it breath.

Splashing the lamb's head with cold water will also often help to generate a response.

Check for other lambs before presenting the lamb to the ewe.

With a difficult birth, it is best to check that no tears have occurred that may need a stitch.

There is an increased risk of prolapse following a very difficult birth and, as such, anti-inflammatories may need to be administered by your vet if you think this may be an issue.

A stitch or harness may also be needed to rectify this situation, while antibiotic treatment may also be warranted.

Always remember hygiene

Hygiene is critical. Wash your hands in soap and water before attending to the ewe. Rubber disposable gloves should be worn.

Clean the lamb's head of any foreign material if it is to be reinserted into the ewe.

Likewise, if a prolapse has occurred, it is vital to practice good hygiene.

Remember to wash hands and where coming in contact with pregnant women, change your clothes, as zoonotic diseases can harm the unborn child.

Read more

A full complement of lambing aids can reduce stress at lambing

Investing in sheep for my old age

The recent increase in optimism in the sheep sector is thankfully getting more young people involved, while there are also farmers converting to sheep or possibly returning to lambing ewes after a period of time.

In the recent Irish Farmers Journal reader survey, a request which arose on a number of occasions was getting back to basics and covering some beginners or refresher-type article.

With lambing ramping up, it is perfect timing to include our first refresher topic on lambing the ewe.

Under normal conditions, a high percentage of ewes generally lamb unassisted. But there are always times where lambs may be presented incorrectly in the birth canal and require assistance or where the ewe may need help in delivering oversized lambs.

This article deals with the many ways in which malpresentations occur, but before delving into this issue, it is important to know when it is time to intervene in potential problems.

Signs of lambing

In the hours before lambing, a ewe will become uneasy or show signs of sickness.

The signs can vary, depending on whether ewes remain outdoors or are housed.

Where lambing outdoors, ewes will tend to separate from the flock. This is especially true of hill and mountain breeds, where their natural instinct is to find a safe sheltered place to lamb.

Ewes lambing indoors often tend to take a similar approach of separating from the flock, but this is harder to detect.

Another indication is ewes failing to come to eat or continually standing and lying or bleating looking for lambs.

Where lambs are present in the same pen, ewes may think other lambs are her own, so she will try to mis-mother these.

For this reason, it is advantageous to remove ewes and lambs as soon as possible to individual lambing pens for a period to develop a strong bond.

In some cases, early signs of labour may be shown two to three hours before lambing actually takes place

During this period, contractions may have started. A lamb is surrounded by two fluid-filled sacks, normally known in practical terms as the first and second water bag.

Frequent contractions will push the first water bag into the cervix, causing its dilation (to make room for the lamb to pass through).

If a ewe is handled too early, this may not have taken place or the lamb may not yet have progressed into the birth canal.

Danger of causing harm

In these circumstances, there is a danger of causing harm to the ewe and the lamb by trying to bring lamb(s) too soon.

This process may take place quickly, but, in some cases, early signs of labour may be shown two to three hours before lambing actually takes place.

It is sometimes hastened by another ewe in the pen lambing.

In addition to lying and standing regularly, ewes may be seen pawing the ground with their front feet.

If the length of time a ewe is lambing is not known and you think there may be problems, it is advisable to handle the ewe to see if everything is OK.

If the birth is progressing normally, the ewe can be left for longer to lamb herself or the lambs can be brought if it is possible to do so.

A sure sign that a lambing is progressing successfully is the hooves of the two legs and a lamb’s nose appearing in the second water bag.

Lambing from expulsion of the first water bag should generally take less than an hour or slightly over it for multiple births.

Dealing with lambing difficulties

The diagrams below will hopefully help you to visualise the different problems that can occur and how these can be rectified.

Oversized lamb

Even though the lamb may be presented in the correct manner, a difficult birth may take place due to oversized lambs or a small ewe/ewe lamb. Using plenty of lubricant will help.

The legs of the lamb should be pulled gently, one at a time, to carefully ease the lamb further out.

Care should be taken when bringing the lamb not to rupture or cause any tears to the vulva of the ewe.

When the lamb is coming, the skin of the vulva may need to be pulled gently back over the head, which should make it easier to bring the lamb.

The force applied should be steady and not jerked. The force should be applied above the hocks (bend in leg) and behind the lamb's ears by using a lambing aid.

Pull the lamb towards the ewe's hocks. If the lamb gets stuck, turning the ewe on her back may help.

If the lamb is stuck at the hips, releasing pressure and then pulling the lamb between the ewe's legs and over the udder frequently helps.

Continuous pressure in one direction where a lamb is stuck at the hips generally does not work.

It is important to use your judgement at the start, as if the lamb is too large, veterinary assistance should be sought, as a caesarean section may be necessary.

Normal lambing

Normal lambing.

In a normal lambing, the two front legs of the lamb will be extended, with the head coming in between them.

The tips of the legs and head may be seen for a significant time before the birth takes place, but once the ewe has pushed the heads and shoulders out, the lamb will generally be delivered rapidly.

Head but no legs

Two legs but no head.

This type of malpresentation is very serious. If not noticed quickly, the lamb's head can swell fast, with the tongue also swelling as time passes.

In this situation, the head needs to be re-inserted into the birth canal, as there is generally no room to bring the legs out.

Lubricant should be used to help get the head back into the ewe.

Before reinserting, clean any foreign material, such as straw or dirt, from the head to minimise the risk of infection.

A lamb born in this situation will need careful attention and more than likely stomach tubing, as normal sucking behaviour will usually be compromised.

Head and one leg

Head and one leg.

This is similar to a head and no legs, but just not quite as serious.

Where possible, try to bring the other leg before delivering the lamb.

If there is plenty of room, it may just be a case of turning the leg upward.

If this is not possible, it will require reinserting the leg and head into the birth canal.

Use a lambing cord or aid to keep the head in the right position if you think it may fall back out of place.

In some cases where the lamb is small, especially with multiple births, it may be possible to bring the lamb with one leg and the head.

The head should again be gripped behind the ears and not the mouth or jaw.

Two legs but no head

Two legs but no head.

This can be tricky, as when a lamb's head has gone back, it is generally difficult to get the head and legs lining up correct again.

A lambing aid or a lambing cord, which can essentially be a piece of washing line, for example, can be used to grip the lamb's head.

Again, catch behind the ears and loop over the head.

The head can be brought forward with the cord, while the legs can be brought with the other hand.

Pull the head and the legs gradually into the birth canal, where the lamb may be oversized or the birth canal is tight.

Two lambs at once

Two lambs at once.

A malpresentation involving multiple lambs requires patience and visualisation of what way the lambs are fixed inside the ewe.

Try to locate the two legs and the head of the same lamb and then see if the lamb can be brought.

Again, it may require the use of a lambing aid to guide the head or legs forward.

Lamb backwards - two legs back

Lamb backwards - two legs back.

This is also known as breech presentation, with both legs back and situated neatly under the lamb.

It is generally best to deliver the lamb in the position it is in, rather than trying to turn the lamb in the uterus.

Doing so increases the risk of breaking the umbilical cord and drowning the lamb.

Raise the tail firstly and then try to raise the back legs into the birth canal one at a time.

Grabbing the leg at the fetlock (turn of leg) is generally best, then raising the leg into the birth canal.

This may require pushing the lamb back towards the uterus to have more room to work.

Lamb backwards - two legs coming

Lamb backwards- two legs coming.

This situation is usually relatively easy to overcome, as long as the lamb is not over-sized.

Bring the lamb backwards as quick as possible. Delaying delivery once you have started to assist the birth may result in the umbilical cord breaking and the lamb drowning in fluid.

Lamb backwards - one leg back

Lamb backwards - one leg down and one leg coming.

This is very similar to two legs coming backwards.

Raise the second leg, which generally requires pushing the lamb back towards the uterus to make room to raise the leg.

Deliver as advised above.

Dealing with the newborn lamb

Once a lamb has been delivered, deal with it to ensure it is OK.

If a lamb is showing little sign of life, holding it upside down by the legs and swinging it gently in a 180-degree arc may help to clear the lungs of any fluids.

Only do this for a short period of a few swings.

Rubbing the lamb's ribs may also help. Also wipe any mucus from around the mouth and ears.

Where a lamb appears to be having problems breathing, a piece of straw can be inserted gently into its nose to help it breath.

Splashing the lamb's head with cold water will also often help to generate a response.

Check for other lambs before presenting the lamb to the ewe.

With a difficult birth, it is best to check that no tears have occurred that may need a stitch.

There is an increased risk of prolapse following a very difficult birth and, as such, anti-inflammatories may need to be administered by your vet if you think this may be an issue.

A stitch or harness may also be needed to rectify this situation, while antibiotic treatment may also be warranted.

Always remember hygiene

Hygiene is critical. Wash your hands in soap and water before attending to the ewe. Rubber disposable gloves should be worn.

Clean the lamb's head of any foreign material if it is to be reinserted into the ewe.

Likewise, if a prolapse has occurred, it is vital to practice good hygiene.

Remember to wash hands and where coming in contact with pregnant women, change your clothes, as zoonotic diseases can harm the unborn child.

Read more

A full complement of lambing aids can reduce stress at lambing

Investing in sheep for my old age

SHARING OPTIONS