There’s an old saying that people stand together or they fall apart. It may well be the defining sentiment for farming in 2026.

It’s shaping up to be a challenging year on many fronts. For the dairy sector, the sharp fall in milk price across the last few months of 2025 will see farmers calving down in a scenario where costs are barely covered by income.

Yes, feed should get cheaper, and certainly no dearer, unless grain markets rebound.

But fertiliser has the CBAM payment to absorb, and we all know that farmers will be paying every cent of that. A repeat of the buoyant calf prices of the year gone out would be welcome, but the spectre of bluetongue hangs over that prospect. And then there’s TB, with reactor numbers projected to rise sharply again this year.

For the beef sector, bluetongue is only one of a number of challenges.

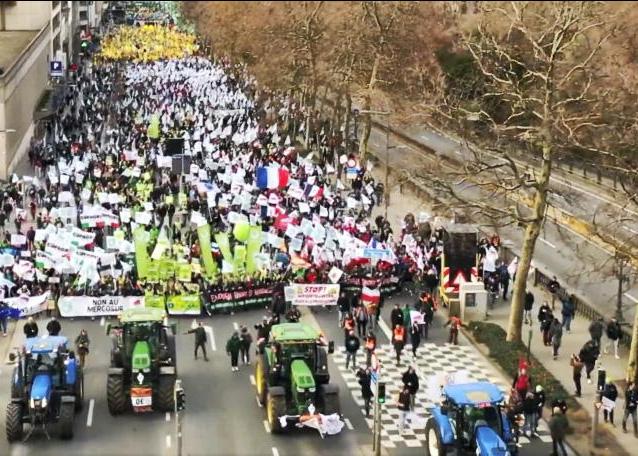

Mercosur can’t be kicked down the road much further, 2026 will be the year it sinks or swims. Suckler numbers continue to fall, despite the record prices for weanlings, and concerns about kill capacity will only grow, particularly if bluetongue affects cross-border trade.

Above all, CAP negotiations will affect suckler and beef farmers. To paraphrase Rick in Casablanca, maybe not in 2026, maybe not the year after, but soon, and for the rest of the working lives of the average beef farmer.

Despite the best cattle prices in living memory, the most recent Teagasc National Farm Survey showed that cattle rearing (mainly suckler) farmers earned less than their direct payments. In other words, they would have lost money in 2024 without CAP payments. Finishing farms were only slightly less dependent on direct payments. A CAP budget cut of 20% would be a death knell for the beef sector, whether Mercosur comes or not.

The same applies to sheep farming. Record prices, falling numbers, aging farmers, and an utter dependence on direct payments – CAP comprised 102% of sheep farmer incomes in 2025.

The tillage sector’s issues are deep. The cost of land rental, the necessity of a certain scale for viability, the cost of machinery maintenance and replacement all combine to make it a high-cost operation. And prices that looked attainable when Ireland was winning Eurovisions don’t pay the bills. There won’t be any Eurovision for Ireland in 2026, there may not be much tillage farming by the end of the decade.

Somehow, Minister Martin Heydon has to sell a narrative that all farmers are interdependent. He must paint a scenario where the competing political priorities of nitrates (now sorted), Mercosur, and the CAP budget can all be catered for. He must provide reassurance over calf exports while calming tillage farmers down over feed imports.

And he and his department must shape the outline of a CAP proposal that maintains viability in vulnerable sectors, when every sector outside dairying is vulnerable.

That’s quite a challenging to-do list. He’ll need the support of the farm organisations, particularly the IFA.

In the final line of Casablanca Rick tells the police commissioner “Louis, I think this could be the beginning of a beautiful relationship”. Can Martin Heydon and Francie Gorman develop a working relationship that holds farmers together through turbulent times?

SHARING OPTIONS