Red or white? It wasn’t too long ago when these were your only wine options when dining out. But today, wine is Ireland’s second favourite alcoholic beverage, according to the 2020 Drinks Ireland/Ibec Irish Wine Market Report.

Enjoying 32% of the overall market share for Irish alcohol sales, Chilean wine is the nation’s favourite, followed by Spanish, Australian, French and Italian.

The usual “buy Irish” isn’t relevant in this context, because historically Ireland does not have a winemaking or viticulture (the cultivation of grapevines) tradition.

However, lacking tradition doesn’t mean we have never grown grapes for wine in the past (we have) or that we lack potential for a future wine industry (we don’t).

Decades ago, aficionados might have scoffed at the idea of British wine, but today wines from that region rank increasingly high in terms of quality and taste. According to WineGB’s (the national association for the English and Welsh wine industry) 2023 Industry Report, viticulture is the fastest-growing agricultural sector in Britain, with projections of producing 22 million bottles of wine per year by the year 2030. Currently, 3,928h of vineyards can be found in Britain – this is up by 74% in the past five years.

Of any other wine-producing country in Europe, Britain’s climate is most similar to Ireland’s – the question is: could we develop an indigenous industry of our own?

David Llewyn grows grapes for wine and sells it commercially from his farm in Lusk Co Dublin. \ Claire Nash

Lusca wines

While we don’t have a winemaking tradition, Ireland is still listed as a wine producing nation by the European Commission.

Currently there are around 10 productive Irish vineyards, of varying sizes, with hopes to sell wine commercially.

One of Ireland’s best established winemakers is David Llewellyn of Lusca Vineyard. David grows other fruits commercially, but his line of Lusca wines (named for his locality, Lusk, Co Dublin) are his pièces de résistance.

In the 1980s, David studied horticulture before moving to Germany, where he was first exposed to winemaking. Upon his return to Ireland, he started experimenting with grape growing. This led to further study at University College Dublin (UCD), where he researched viticulture in Ireland and how it could work.

After decades of winemaking, he is now in a place where he is consistently happy with his process and the results of the fruits of his labour (so to speak).

“Our limitation is the temperature; the cool summers,” he explains. “You can’t grow vines just anywhere. Where I am, it is sheltered. It would be among the better corners of the country to try growing grapes for wine, because the sunshine is almost as good as in Wexford and temperatures are almost as good as warmer parts of the country.

“We’re close enough to the coast that we get very little frost; 10 miles further inland I could be faced with a wipe-out every few years.”

The late frosts, David explains, are the real killers. The vines themselves are hardy and can withstand temperatures colder than -20°C, but the vines start to bud toward the end of April. A late frost can kill them off and ruin a season of growing

“We’ve a fantastic crop this year, but you wouldn’t have a hope of growing cabernet sauvignon or Shiraz outdoors,” he says. “It would grow, the vine would look healthy, but the grapes would never ripen. Even pinot noir and chardonnay, which are being grown in England now for sparkling wine, are only found in the best parts of Southern England – in Ireland you could forget about them.”

David didn't invest in top of the line equipment; instead he uses what he already has around the farm (as much as possible) to make his wine \ Claire Nash

Perfect grape

So what grape variety has David had success with?

The answer is the Rondo: a hybrid grape developed in the 1960s by combining old European, which are best for winemaking, and Russian vines, which are naturally pest and disease-resistant.

It is an “early maturing” vine; making it ideal for growing outdoors in regions with shorter summers.

“Conventional vines are one of the most sprayed crops in the world,” David says. “I don’t spray these grapes – I’m lucky – and that’s partly because I’m isolated here in Ireland; I’m not in a wine region surrounded by sources of disease. But it’s also because I’m growing these hybrid varieties. It’s the best of both worlds.”

In total, David has less than one acre of vineyard and the vines we see on our visit were first planted in 2012. Grapevines usually take up to five years to produce enough fruit for winemaking. David explains that there are a few different ways of pruning the vines to prepare them for the next growing season, but his preferred method is pruning all of the vines back completely each winter; leaving just two well-positioned, strong-looking branches on the vine.

These two branches will develop the buds and the vines which will produce the following year’s grapes.

When the grapes ripen, David uses a tool called a refractometer to measure the sugar content. Once they hit the right level, it is time to harvest and press. David sold his first wines commercially in 2006 and says that his litmus test, when it comes to quality, is often his own palate.

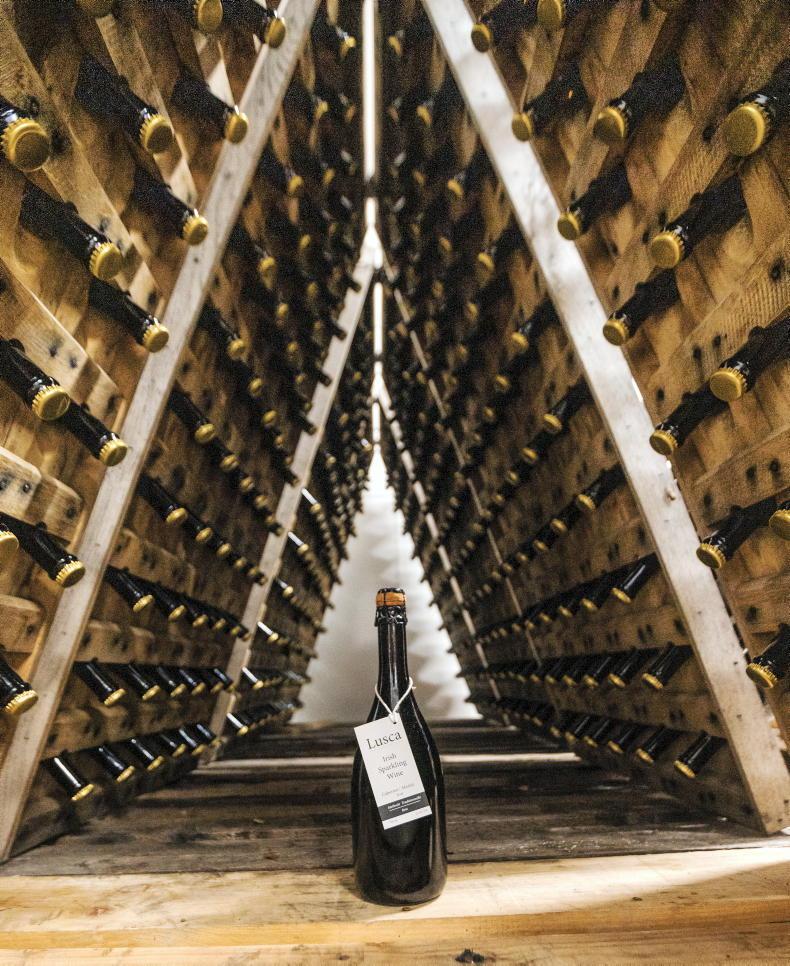

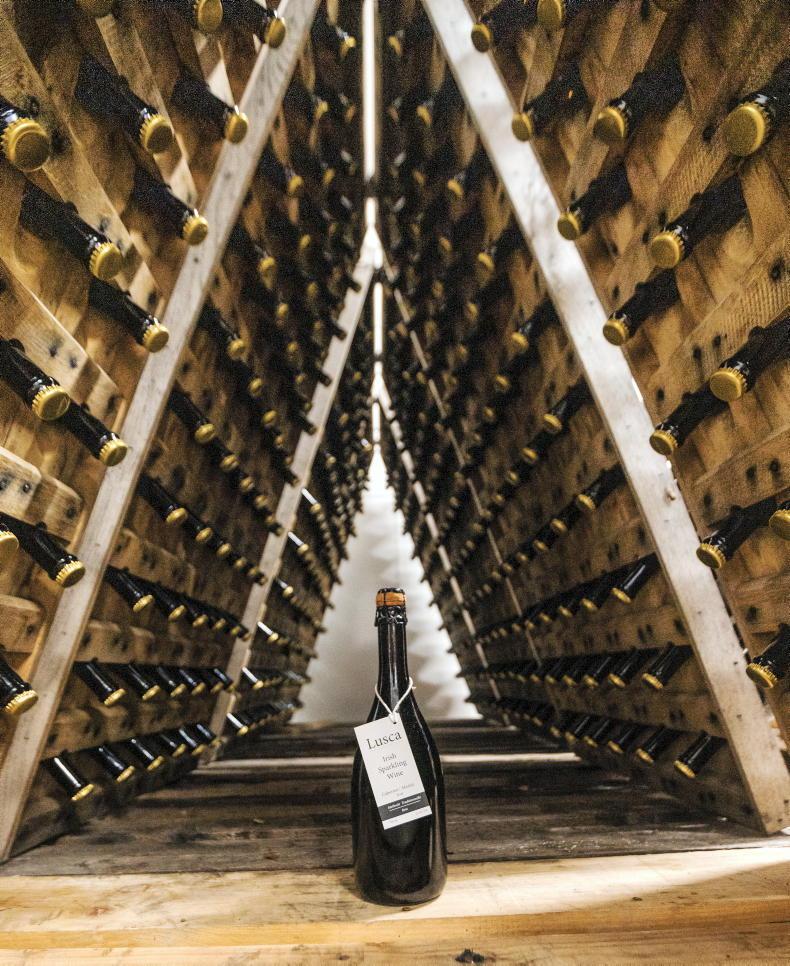

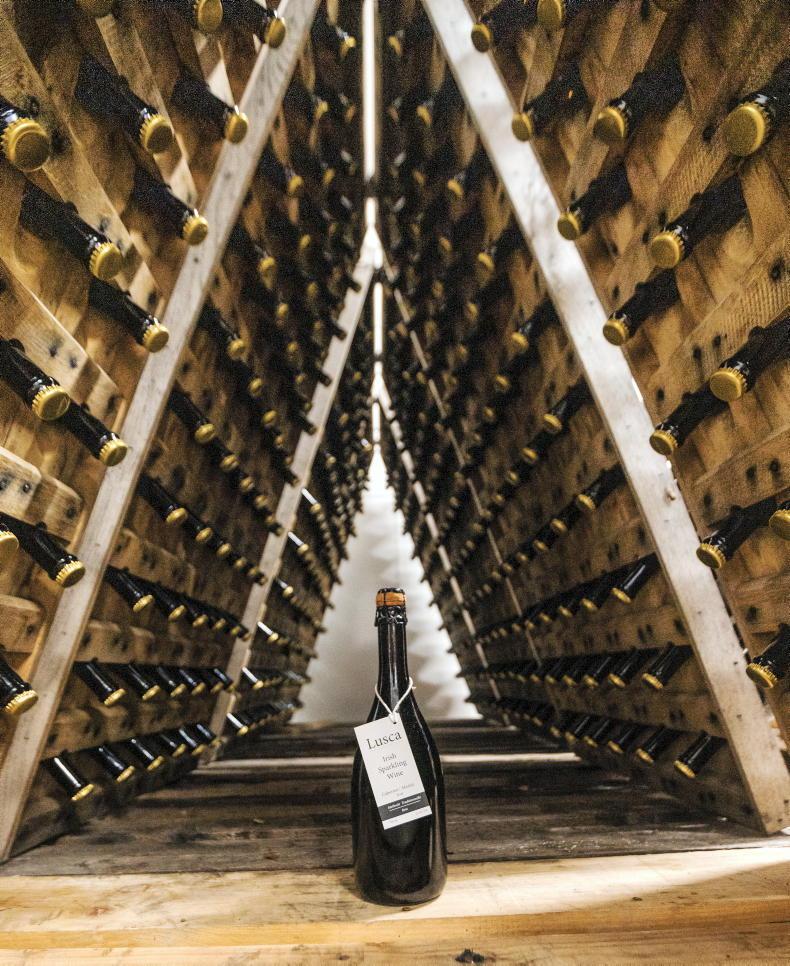

David's Lusca Sparkling wine rests in this triangular holder while secondary fermentation (how the wine gets its fizz) takes place in the bottle \ Claire Nash

“I have to like the wine before I dare to sell it to somebody else. If I don’t like it; I won’t sell it. Thankfully, I haven’t had a vintage in more than ten years that I wasn’t happy with.”

In recent years, David started experimenting with sparkling wine and was pleasantly surprised by the results. Now, he is devoting even more of his harvest to making his Lusca sparkling – a light rosé offering with notes of buttery pastry and fresh black cherry and red berry flavours.

David says, “People kept suggesting sparkling wine so I gave it a go and it was beautiful, people loved it. I thought, ‘I should have been doing this years ago.’ Sparkling wines are suited to colder climates; that’s why they make it in the Champagne [region of France] – it’s too cold to grow the grapes that they grow in the south. When it’s made well, it’s a gorgeous drink.”

Between this newer offering and his two existing red wines (Lusca Rondo, €60 and Lusca Cabernet/Merlot, €48.50), David is producing around 1,500 bottles of wine per year. The Lusca Sparkling retails at €70 per bottle.

“It is relatively expensive,” he admits. “But if you think we can produce cheap Irish wine you’re deluding yourself. In England they have an established industry; they’re producing millions of bottles each year and it is [still] expensive. We’re at even more of a disadvantage because we don’t have the climate that they have.”

Michelin Star

Chef JP McMahon owns and operates Michelin star restaurant Aniar in Galway. He recently starting serving David’s Lusca Sparkling and says the reception from diners has been excellent.

“We’ve decided to offer it to the customer when they come in because we offer sparkling to begin the meal, and I think around 90% of our customers have decided to try it because it’s quite a unique drink,” he tells Irish Country Living.

JP also offers the Lusca Sparkling as part of Aniar’s Irish drinks pairing (which includes locally made beers and ciders) and has paired it with menu items like their tartare and their goat’s curd.

“I think we’re going to see more Irish vineyards [in the future], we just have to find out which grapes do better in Ireland,” he explains. “I think it’s exciting, and it mirrors what other colder climates are doing in other parts of the world [with wine].”

While David’s winery is successfully “washing its face,” as he puts it, for being so small scale and standing on its own (in a business sense), he is cautious about the idea of scaling up production because the market continues to be very niche. Instead he chooses to make the best of what he currently has. Lacking a thriving winemaking community or any kind of advisory body (Teagasc and Bord Bia have both confirmed to Irish Country Living that they have not yet researched potential opportunities within Irish viticulture), winemaking has, at times, felt like a lonely place.

“Realistically, there are so many disadvantages to growing wine in Ireland,” David says. “At the moment, it’s up to those who are growing and planting to figure things out for themselves. At my tiny scale, I’m better off paddling my own canoe and doing things as economically as I can.”

For queries, readers can call 0872843879

Read more

Taste Tradition: a life of family, farming and hospitality

Should Irish farmers grow hemp?

Red or white? It wasn’t too long ago when these were your only wine options when dining out. But today, wine is Ireland’s second favourite alcoholic beverage, according to the 2020 Drinks Ireland/Ibec Irish Wine Market Report.

Enjoying 32% of the overall market share for Irish alcohol sales, Chilean wine is the nation’s favourite, followed by Spanish, Australian, French and Italian.

The usual “buy Irish” isn’t relevant in this context, because historically Ireland does not have a winemaking or viticulture (the cultivation of grapevines) tradition.

However, lacking tradition doesn’t mean we have never grown grapes for wine in the past (we have) or that we lack potential for a future wine industry (we don’t).

Decades ago, aficionados might have scoffed at the idea of British wine, but today wines from that region rank increasingly high in terms of quality and taste. According to WineGB’s (the national association for the English and Welsh wine industry) 2023 Industry Report, viticulture is the fastest-growing agricultural sector in Britain, with projections of producing 22 million bottles of wine per year by the year 2030. Currently, 3,928h of vineyards can be found in Britain – this is up by 74% in the past five years.

Of any other wine-producing country in Europe, Britain’s climate is most similar to Ireland’s – the question is: could we develop an indigenous industry of our own?

David Llewyn grows grapes for wine and sells it commercially from his farm in Lusk Co Dublin. \ Claire Nash

Lusca wines

While we don’t have a winemaking tradition, Ireland is still listed as a wine producing nation by the European Commission.

Currently there are around 10 productive Irish vineyards, of varying sizes, with hopes to sell wine commercially.

One of Ireland’s best established winemakers is David Llewellyn of Lusca Vineyard. David grows other fruits commercially, but his line of Lusca wines (named for his locality, Lusk, Co Dublin) are his pièces de résistance.

In the 1980s, David studied horticulture before moving to Germany, where he was first exposed to winemaking. Upon his return to Ireland, he started experimenting with grape growing. This led to further study at University College Dublin (UCD), where he researched viticulture in Ireland and how it could work.

After decades of winemaking, he is now in a place where he is consistently happy with his process and the results of the fruits of his labour (so to speak).

“Our limitation is the temperature; the cool summers,” he explains. “You can’t grow vines just anywhere. Where I am, it is sheltered. It would be among the better corners of the country to try growing grapes for wine, because the sunshine is almost as good as in Wexford and temperatures are almost as good as warmer parts of the country.

“We’re close enough to the coast that we get very little frost; 10 miles further inland I could be faced with a wipe-out every few years.”

The late frosts, David explains, are the real killers. The vines themselves are hardy and can withstand temperatures colder than -20°C, but the vines start to bud toward the end of April. A late frost can kill them off and ruin a season of growing

“We’ve a fantastic crop this year, but you wouldn’t have a hope of growing cabernet sauvignon or Shiraz outdoors,” he says. “It would grow, the vine would look healthy, but the grapes would never ripen. Even pinot noir and chardonnay, which are being grown in England now for sparkling wine, are only found in the best parts of Southern England – in Ireland you could forget about them.”

David didn't invest in top of the line equipment; instead he uses what he already has around the farm (as much as possible) to make his wine \ Claire Nash

Perfect grape

So what grape variety has David had success with?

The answer is the Rondo: a hybrid grape developed in the 1960s by combining old European, which are best for winemaking, and Russian vines, which are naturally pest and disease-resistant.

It is an “early maturing” vine; making it ideal for growing outdoors in regions with shorter summers.

“Conventional vines are one of the most sprayed crops in the world,” David says. “I don’t spray these grapes – I’m lucky – and that’s partly because I’m isolated here in Ireland; I’m not in a wine region surrounded by sources of disease. But it’s also because I’m growing these hybrid varieties. It’s the best of both worlds.”

In total, David has less than one acre of vineyard and the vines we see on our visit were first planted in 2012. Grapevines usually take up to five years to produce enough fruit for winemaking. David explains that there are a few different ways of pruning the vines to prepare them for the next growing season, but his preferred method is pruning all of the vines back completely each winter; leaving just two well-positioned, strong-looking branches on the vine.

These two branches will develop the buds and the vines which will produce the following year’s grapes.

When the grapes ripen, David uses a tool called a refractometer to measure the sugar content. Once they hit the right level, it is time to harvest and press. David sold his first wines commercially in 2006 and says that his litmus test, when it comes to quality, is often his own palate.

David's Lusca Sparkling wine rests in this triangular holder while secondary fermentation (how the wine gets its fizz) takes place in the bottle \ Claire Nash

“I have to like the wine before I dare to sell it to somebody else. If I don’t like it; I won’t sell it. Thankfully, I haven’t had a vintage in more than ten years that I wasn’t happy with.”

In recent years, David started experimenting with sparkling wine and was pleasantly surprised by the results. Now, he is devoting even more of his harvest to making his Lusca sparkling – a light rosé offering with notes of buttery pastry and fresh black cherry and red berry flavours.

David says, “People kept suggesting sparkling wine so I gave it a go and it was beautiful, people loved it. I thought, ‘I should have been doing this years ago.’ Sparkling wines are suited to colder climates; that’s why they make it in the Champagne [region of France] – it’s too cold to grow the grapes that they grow in the south. When it’s made well, it’s a gorgeous drink.”

Between this newer offering and his two existing red wines (Lusca Rondo, €60 and Lusca Cabernet/Merlot, €48.50), David is producing around 1,500 bottles of wine per year. The Lusca Sparkling retails at €70 per bottle.

“It is relatively expensive,” he admits. “But if you think we can produce cheap Irish wine you’re deluding yourself. In England they have an established industry; they’re producing millions of bottles each year and it is [still] expensive. We’re at even more of a disadvantage because we don’t have the climate that they have.”

Michelin Star

Chef JP McMahon owns and operates Michelin star restaurant Aniar in Galway. He recently starting serving David’s Lusca Sparkling and says the reception from diners has been excellent.

“We’ve decided to offer it to the customer when they come in because we offer sparkling to begin the meal, and I think around 90% of our customers have decided to try it because it’s quite a unique drink,” he tells Irish Country Living.

JP also offers the Lusca Sparkling as part of Aniar’s Irish drinks pairing (which includes locally made beers and ciders) and has paired it with menu items like their tartare and their goat’s curd.

“I think we’re going to see more Irish vineyards [in the future], we just have to find out which grapes do better in Ireland,” he explains. “I think it’s exciting, and it mirrors what other colder climates are doing in other parts of the world [with wine].”

While David’s winery is successfully “washing its face,” as he puts it, for being so small scale and standing on its own (in a business sense), he is cautious about the idea of scaling up production because the market continues to be very niche. Instead he chooses to make the best of what he currently has. Lacking a thriving winemaking community or any kind of advisory body (Teagasc and Bord Bia have both confirmed to Irish Country Living that they have not yet researched potential opportunities within Irish viticulture), winemaking has, at times, felt like a lonely place.

“Realistically, there are so many disadvantages to growing wine in Ireland,” David says. “At the moment, it’s up to those who are growing and planting to figure things out for themselves. At my tiny scale, I’m better off paddling my own canoe and doing things as economically as I can.”

For queries, readers can call 0872843879

Read more

Taste Tradition: a life of family, farming and hospitality

Should Irish farmers grow hemp?

SHARING OPTIONS