At the start of each intake of University College Cork’s (UCC) Master of Arts in Food Studies and Irish Foodways, programme manager and celebrated Irish food historian, Regina Sexton, always tells her students the same thing.

“I say: ‘This is our course. For two years, we are going to be talking about food, but really, we are going to be talking about everything that isn’t food, because food is a way of understanding the human condition. It’s understanding how to be human, as well, because the relationship you build with food [or the relationships imposed upon us with our food] has got to do with the economy, politics, the environment, philosophy, power – everything.’”

Regina’s passion for Irish food history is contagious and invigorating.

Anyone with an understanding of food systems, agriculture and/or politics can be forgiven for being just a bit jaded.

It seems there are often more unsolvable problems than solutions as we face into the future. Interviewing Regina doesn’t feel like an interview – it feels, in some cathartic way, like therapy.

As I walk back to my car after our conversation, I think that if I am feeling this way after just a 30-minute chat, her students must graduate feeling like they can conquer the world.

History and food

Growing up in Cork city, Regina’s world revolved around two things: history and food; both thanks to the influence of her father, who was a third generation baker and self-taught history buff.

“My father, grandfather and great-grandfather were bakers in the city,” she says.

“The first of them came from west Cork into the city after the Famine, and that’s a time when you see a lot of socio-economic and cultural changes in food.”

She refers to the increased importation of wheat from North America and within Europe during this time, which led to a slew of small, family owned bakeries.

Her father grew up in this world and rebelled against the subsequent modernisation of Irish food.

“He’d come home and give out about it all; how they were now pressing a button and the big plant would make the bread untouched by hand. Of course, we thought he was a bit of a crank,” Regina recalls, laughing.

“We were the children of this era where shop-bought, industrial foods were all the excitement. I now look back and understand that he was a commentator and an observer of the big changes that were happening at the time.”

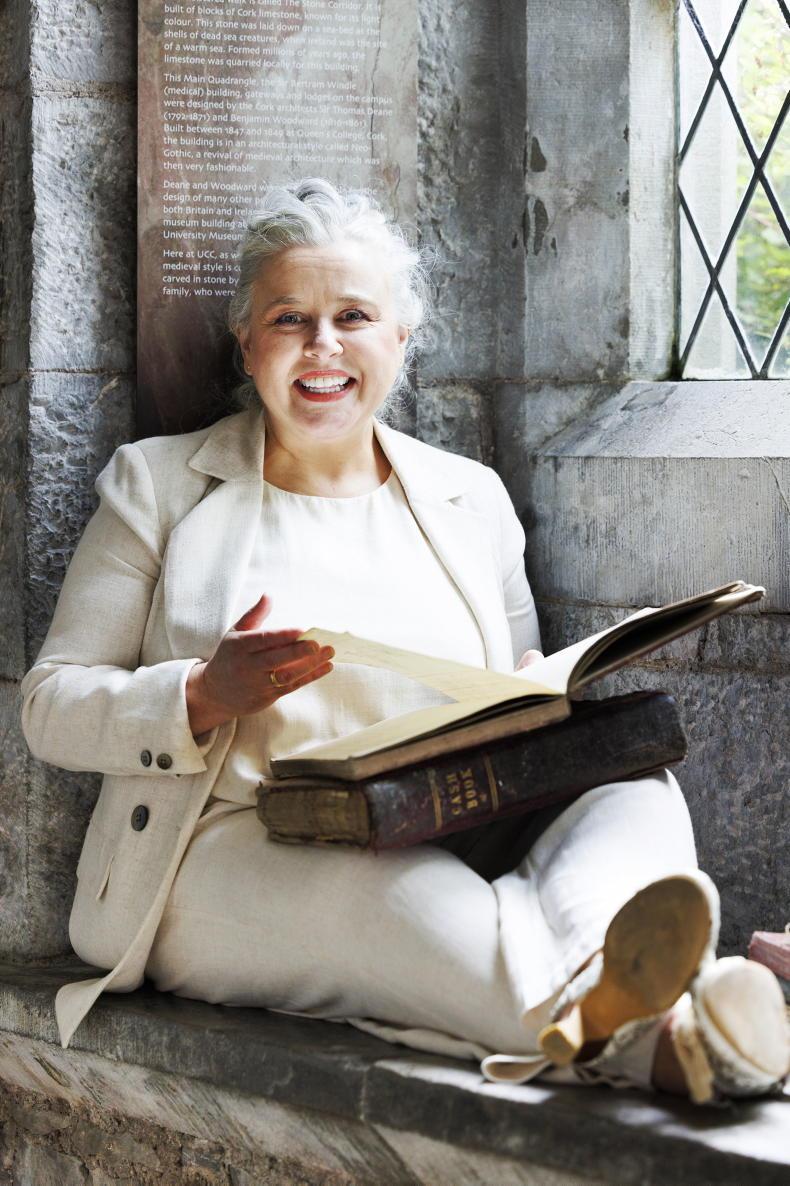

Regina Sexton with the late Myrtle Allen at Ballymaloe Litfest in 2014.

Life of research

When Regina first attended college at UCC, she studied history.

She particularly enjoyed her classes with famed Irish historian Donnchadh Ó Corráin, whose focus was on early medieval Ireland, including the foods which were eaten and produced during those times.

Regina found these lectures particularly fascinating, saying Donnchadh “sowed the seed” for food history deeply into her brain.

After college, she spent some time working in Paris which opened her eyes to how other nations intertwine culture with cuisine, and made her consider the Irish food she grew up eating in a completely different way.

“People would invite you to their house and start talking about food in great detail,” she says.

“I was there going, ‘I’ve nothing to say. In Ireland we just have meat, potatoes and vegetables.’ We had chicken but in France they had poulet de brest.”

When she moved back home, Regina dove back into study, researching early medieval grain. At the same time, she lived in a local east Cork castle as a caretaker.

The location was fortuitous: it led to her meeting Myrtle and Darina Allen at nearby Ballymaloe.

She helped Darina with her book Irish Traditional Cooking and would go on to work with RTÉ on an eight-part docuseries called A Little History of Irish Food, which took the same name as a popular book Regina wrote in 1997.

“We did each programme by food category, like dairy, cereals, fish and sweets,” she explains.

“It was a fantastic experience for me, because we were talking to food producers and historians who had never thought of looking at history through the lens of food. I also wrote a column for the Irish Examiner called Taste of the Past for 15 years.”

In the lead-up to the launch of UCC’s Master’s in Food Studies and Irish Foodways in 2019, Regina was already teaching short courses at the university and with the Food Industry Training Unit on their Diploma in Speciality Food Production.

Through these courses and others on offer, she says much of the groundwork for the Master’s programme was laid.

“I thought it would be great if we developed a course that would bring together university research strengths [on the topic],” she explains.

While it wasn’t easy for the university to decide where such a programme, with elements from food science, nutrition, business and history (among many other topics), might fit; they eventually decided it would work as a trans-disciplinary programme.

This was meaningful for Regina, who often felt she worked between the worlds of food and history.

By finding a place for the programme within the university, she perhaps finally realised her own place, as well, as one of Ireland’s very few food historians.

The launch of the Master’s solidified what so many food professionals and writers have known for decades: that Irish food is not a “soft” topic.

“People tend to forget: our largest indigenous industry is making food,” Regina says.

“We are an island of farmers. They are the foundation that we all stand on. We need to think about food holistically, through a whole-systems approach, and farmers need to be recognised for how important they are to Irish society. We also need to think about how tragic it would be if they weren’t part of Irish society.”

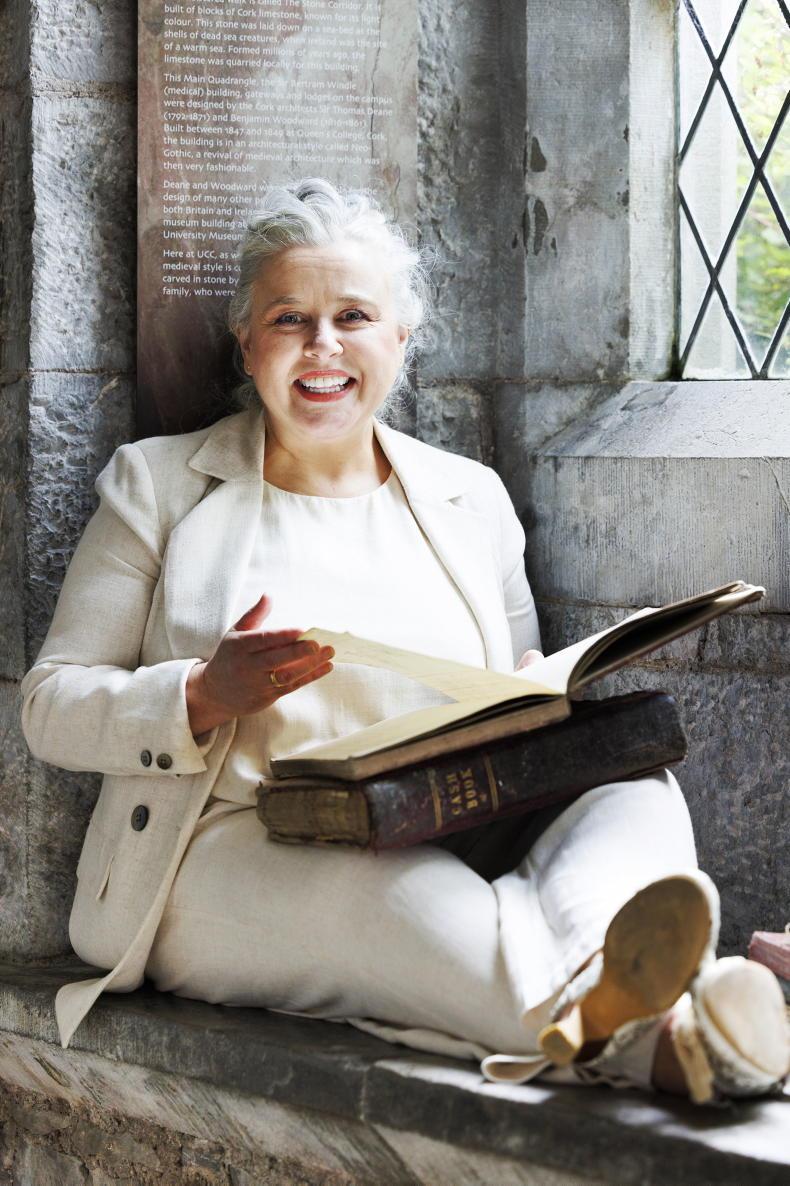

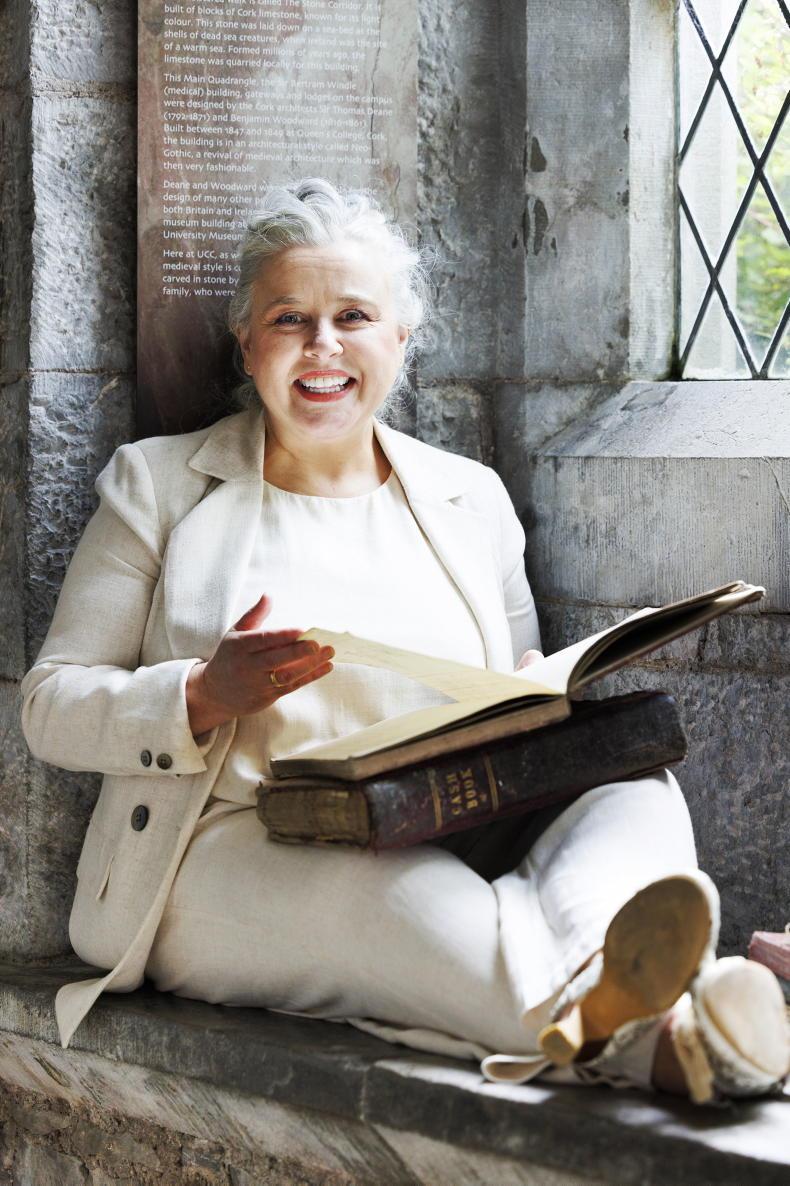

Regina Sexton, Food and Culinary Historian, UCC. \ Donal O' Leary

Food heroes

To look to the future, we must be able to look to our past.

This is what Regina’s father was doing all those years ago, and you could say the same for one of Regina’s Irish food heroes: Myrtle Allen.

Myrtle, who passed in 2018, would be celebrating her 100th birthday this year. Additionally, this year is the 60th anniversary of her beloved Ballymaloe House, which first opened to the public in 1964.

“I got to know Myrtle because we were living close to Ballymaloe, but also through a group she set up called the ‘Cork Free Choice Consumer Group’,” Regina says, smiling.

“This was a group meeting in the 1990s and we’d discuss things like chicken – why this chicken might be nicer than that chicken, for example. And she would bring in producers and they’d talk and explain. I got to know her and I realised her power, as she was now outside the kitchen.”

For years now, Regina has been researching Myrtle’s life and work. Often referring to Myrtle as a “polymath”, or someone who had a huge amount of interests, this research has been her primary focus.

“When she passed away, I suggested the university in Cork recognise her work, so we started the annual ‘Myrtle Allen Memorial Lecture’,” she says.

“When I went to discuss that with her family to see if ‘they’d agree, they said it was a fantastic idea and also said that upstairs there were a lot of papers she collected over time; they thought I might find something in there. Her office was just flowing with papers and documentation from the restaurant.”

After finding even more documentation – like old menus – in the attic at Ballymaloe House, Regina asked if the Boole Library archives at UCC might take the collection, which they did.

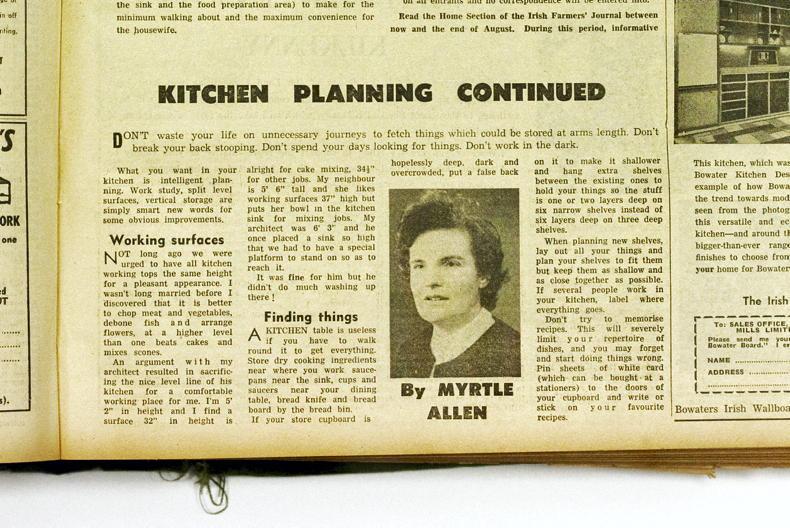

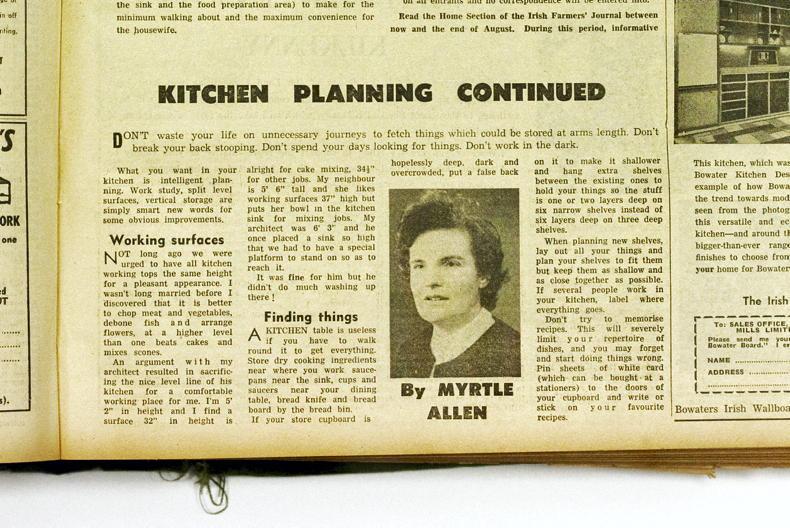

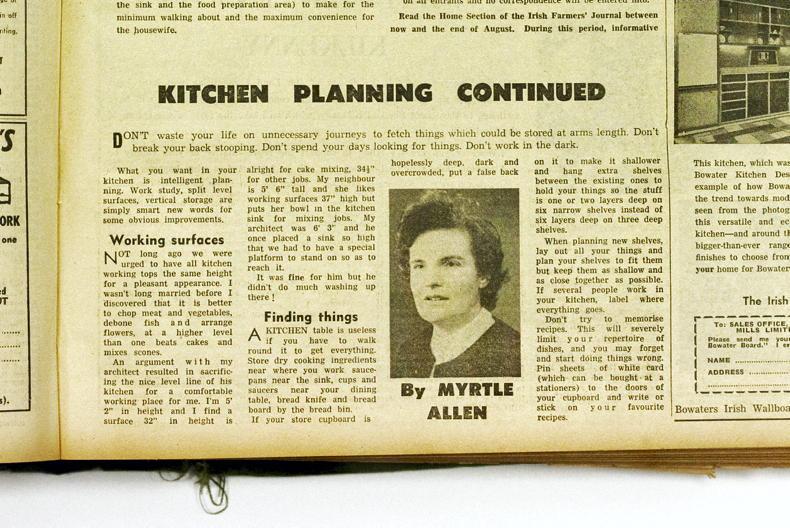

Besides her kitchen papers, Myrtle’s cookery columns from the Irish Farmers Journal, which began in 1962, are of great interest to Regina.

To her, they show how Myrtle was a catalyst of positive change during a tumultuous time for Irish food and agriculture.

One of Myrtle Allen’s column published in the Irish Farmers Journal in 1964, the same year Ballymaloe House first opened to the public.

“She was speaking up and giving a voice to tradition,” Regina states. “Farmers, at this time, were thinking about joining the EEC [European Economic Community]; they were looking forward and the past was bringing them down.

“The line you hear about Myrtle is that she was ‘before her time’, and she was, but she was also very much of her time because she was

bang in the middle of all this socio-cultural change.

“Her column was for everyone,” she adds. “The articles were not just writing about food or sharing a recipe – there was also a message in there, which was delivered again through the recipe.

“It was almost like subliminal messaging going out from her via the Farmers Journal.

“So that’s what I’m looking at, at the moment. This idea of her looking at Ireland in the 1960s, through her unique perspective.”

Read more

The future of dairy alternatives

It's all down to dad: Irish businesses who are keeping things in the family

At the start of each intake of University College Cork’s (UCC) Master of Arts in Food Studies and Irish Foodways, programme manager and celebrated Irish food historian, Regina Sexton, always tells her students the same thing.

“I say: ‘This is our course. For two years, we are going to be talking about food, but really, we are going to be talking about everything that isn’t food, because food is a way of understanding the human condition. It’s understanding how to be human, as well, because the relationship you build with food [or the relationships imposed upon us with our food] has got to do with the economy, politics, the environment, philosophy, power – everything.’”

Regina’s passion for Irish food history is contagious and invigorating.

Anyone with an understanding of food systems, agriculture and/or politics can be forgiven for being just a bit jaded.

It seems there are often more unsolvable problems than solutions as we face into the future. Interviewing Regina doesn’t feel like an interview – it feels, in some cathartic way, like therapy.

As I walk back to my car after our conversation, I think that if I am feeling this way after just a 30-minute chat, her students must graduate feeling like they can conquer the world.

History and food

Growing up in Cork city, Regina’s world revolved around two things: history and food; both thanks to the influence of her father, who was a third generation baker and self-taught history buff.

“My father, grandfather and great-grandfather were bakers in the city,” she says.

“The first of them came from west Cork into the city after the Famine, and that’s a time when you see a lot of socio-economic and cultural changes in food.”

She refers to the increased importation of wheat from North America and within Europe during this time, which led to a slew of small, family owned bakeries.

Her father grew up in this world and rebelled against the subsequent modernisation of Irish food.

“He’d come home and give out about it all; how they were now pressing a button and the big plant would make the bread untouched by hand. Of course, we thought he was a bit of a crank,” Regina recalls, laughing.

“We were the children of this era where shop-bought, industrial foods were all the excitement. I now look back and understand that he was a commentator and an observer of the big changes that were happening at the time.”

Regina Sexton with the late Myrtle Allen at Ballymaloe Litfest in 2014.

Life of research

When Regina first attended college at UCC, she studied history.

She particularly enjoyed her classes with famed Irish historian Donnchadh Ó Corráin, whose focus was on early medieval Ireland, including the foods which were eaten and produced during those times.

Regina found these lectures particularly fascinating, saying Donnchadh “sowed the seed” for food history deeply into her brain.

After college, she spent some time working in Paris which opened her eyes to how other nations intertwine culture with cuisine, and made her consider the Irish food she grew up eating in a completely different way.

“People would invite you to their house and start talking about food in great detail,” she says.

“I was there going, ‘I’ve nothing to say. In Ireland we just have meat, potatoes and vegetables.’ We had chicken but in France they had poulet de brest.”

When she moved back home, Regina dove back into study, researching early medieval grain. At the same time, she lived in a local east Cork castle as a caretaker.

The location was fortuitous: it led to her meeting Myrtle and Darina Allen at nearby Ballymaloe.

She helped Darina with her book Irish Traditional Cooking and would go on to work with RTÉ on an eight-part docuseries called A Little History of Irish Food, which took the same name as a popular book Regina wrote in 1997.

“We did each programme by food category, like dairy, cereals, fish and sweets,” she explains.

“It was a fantastic experience for me, because we were talking to food producers and historians who had never thought of looking at history through the lens of food. I also wrote a column for the Irish Examiner called Taste of the Past for 15 years.”

In the lead-up to the launch of UCC’s Master’s in Food Studies and Irish Foodways in 2019, Regina was already teaching short courses at the university and with the Food Industry Training Unit on their Diploma in Speciality Food Production.

Through these courses and others on offer, she says much of the groundwork for the Master’s programme was laid.

“I thought it would be great if we developed a course that would bring together university research strengths [on the topic],” she explains.

While it wasn’t easy for the university to decide where such a programme, with elements from food science, nutrition, business and history (among many other topics), might fit; they eventually decided it would work as a trans-disciplinary programme.

This was meaningful for Regina, who often felt she worked between the worlds of food and history.

By finding a place for the programme within the university, she perhaps finally realised her own place, as well, as one of Ireland’s very few food historians.

The launch of the Master’s solidified what so many food professionals and writers have known for decades: that Irish food is not a “soft” topic.

“People tend to forget: our largest indigenous industry is making food,” Regina says.

“We are an island of farmers. They are the foundation that we all stand on. We need to think about food holistically, through a whole-systems approach, and farmers need to be recognised for how important they are to Irish society. We also need to think about how tragic it would be if they weren’t part of Irish society.”

Regina Sexton, Food and Culinary Historian, UCC. \ Donal O' Leary

Food heroes

To look to the future, we must be able to look to our past.

This is what Regina’s father was doing all those years ago, and you could say the same for one of Regina’s Irish food heroes: Myrtle Allen.

Myrtle, who passed in 2018, would be celebrating her 100th birthday this year. Additionally, this year is the 60th anniversary of her beloved Ballymaloe House, which first opened to the public in 1964.

“I got to know Myrtle because we were living close to Ballymaloe, but also through a group she set up called the ‘Cork Free Choice Consumer Group’,” Regina says, smiling.

“This was a group meeting in the 1990s and we’d discuss things like chicken – why this chicken might be nicer than that chicken, for example. And she would bring in producers and they’d talk and explain. I got to know her and I realised her power, as she was now outside the kitchen.”

For years now, Regina has been researching Myrtle’s life and work. Often referring to Myrtle as a “polymath”, or someone who had a huge amount of interests, this research has been her primary focus.

“When she passed away, I suggested the university in Cork recognise her work, so we started the annual ‘Myrtle Allen Memorial Lecture’,” she says.

“When I went to discuss that with her family to see if ‘they’d agree, they said it was a fantastic idea and also said that upstairs there were a lot of papers she collected over time; they thought I might find something in there. Her office was just flowing with papers and documentation from the restaurant.”

After finding even more documentation – like old menus – in the attic at Ballymaloe House, Regina asked if the Boole Library archives at UCC might take the collection, which they did.

Besides her kitchen papers, Myrtle’s cookery columns from the Irish Farmers Journal, which began in 1962, are of great interest to Regina.

To her, they show how Myrtle was a catalyst of positive change during a tumultuous time for Irish food and agriculture.

One of Myrtle Allen’s column published in the Irish Farmers Journal in 1964, the same year Ballymaloe House first opened to the public.

“She was speaking up and giving a voice to tradition,” Regina states. “Farmers, at this time, were thinking about joining the EEC [European Economic Community]; they were looking forward and the past was bringing them down.

“The line you hear about Myrtle is that she was ‘before her time’, and she was, but she was also very much of her time because she was

bang in the middle of all this socio-cultural change.

“Her column was for everyone,” she adds. “The articles were not just writing about food or sharing a recipe – there was also a message in there, which was delivered again through the recipe.

“It was almost like subliminal messaging going out from her via the Farmers Journal.

“So that’s what I’m looking at, at the moment. This idea of her looking at Ireland in the 1960s, through her unique perspective.”

Read more

The future of dairy alternatives

It's all down to dad: Irish businesses who are keeping things in the family

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: