When Jim Callery purchased Strokestown Park House in the late 1970s, aside from the physical estate, he also received all of the historic house records. The Co Roscommon founder of Westward motor group found among them many personal and painful accounts of tenants pleading with their landlord to help them and provide respite during a time when their crops were failing.

Jim was struck by these letters, which started from the year 1846. As it turns out, he had found what is now considered one of the largest collections of famine-related material in the world. This led to the establishment of the National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park House and Gardens in 1994.

National Famine Commemoration Day

The museum recently underwent an extensive re-vamp, with academic coordinator Dr Jason King promising visitors a more interactive experience for those coming to learn about the famine through these archival accounts and artefacts.

“Strokestown was one of the most devastated areas affected by the Great Famine in 1847, and emigrants from Strokestown sailed on some of the worst of the coffin ships,” he says in the National Famine Museum’s latest educational video entitled “The National Famine Museum, Strokestown Park”.

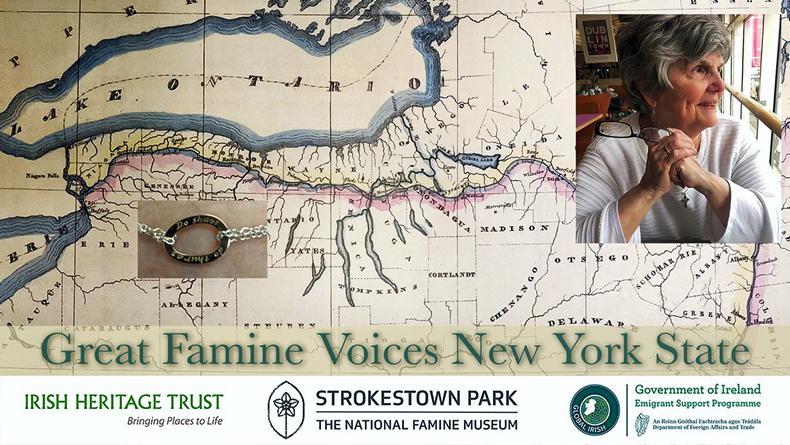

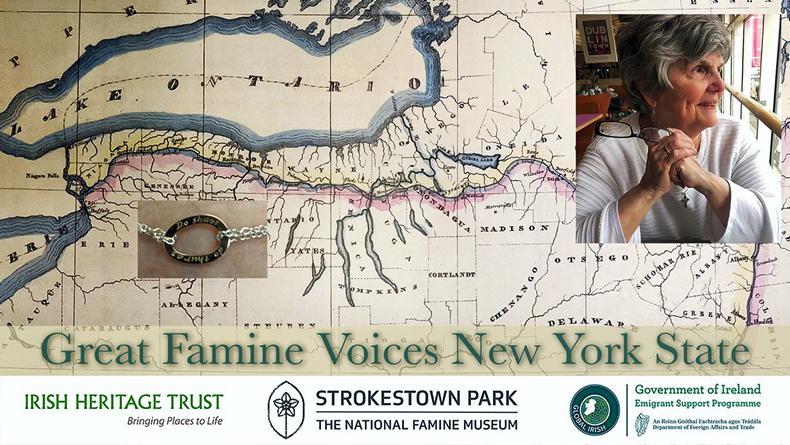

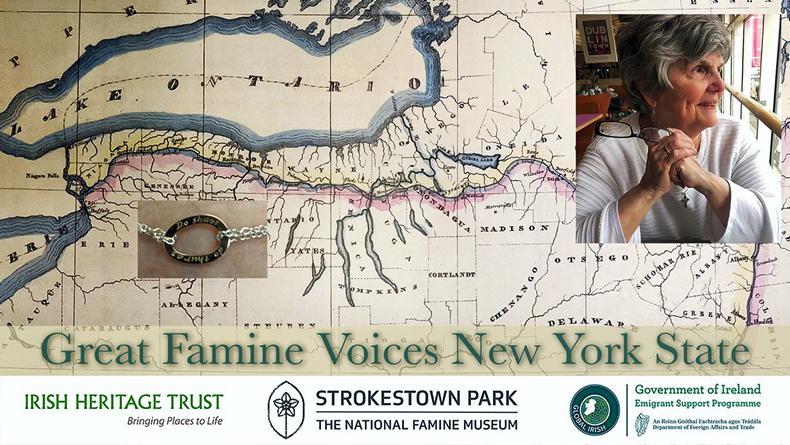

Great Famine Voices of New York State features stories from Irish emigrants in four Irish centres in New York State, along the Erie Canal.

The video was launched both in honour of National Famine Commemoration Day, which took place this past week (15 May) and to celebrate the reopening of the museum, which is set to happen in the coming weeks.

It showcases the museum’s new facilities, interactive displays and archival records, which offer insights into the parallel lives of the cottiers, tenants and landlords who experienced the Great Irish Famine.

Great Famine Voices

Emigration was a major response to the famine as it resulted in many Irish moving abroad; particularly to regions within North America. I recently spoke with Jason about some of the museum’s ongoing projects.

“We have our annual Great Famine Voices season of short films,” he says. “Its purpose is to gather stories from Irish emigrants and their descendants - to recall their stories of migration from Ireland to the United States, Canada and Great Britain (for the most part, during the periods of the Great Hunger, but afterwards as well) and our premiere video this season was [entitled] The Famine Irish in Chicago.”

This series not only documents why Irish emigrants came to America and shares their stories; it also explains and emphasises the significant work Irish immigrants accomplished in building the infrastructure and political landscape of the modern-day United States.

“[The Irish] played a big role in building the [physical] infrastructure, but they also played a very important role in the development of Chicago politics,” Jason explains. “The Famine generation in particular helped build the Democratic Party and played an instrumental role in shaping its policies.”

The series can be viewed on Youtube by searching or subscribing to Great Famine Voices. There will be eight films released this year – the releases began the first week of May and will continue until 19 June.

“As of now, we have released the ‘Famine Irish in Chicago’ and ‘Great Famine Voices New York State’ [videos],” Jason says. “The latter features stories from Irish emigrants in four Irish centres in New York State, along the Erie Canal.”

As is our wont with our Tales from the Parish series, we couldn’t publish this article without sharing one of the stories featured in the Great Famine Voices series. This story is told by Nora Keating of Utica, New York State and features in ‘Great Famine Voices New York State’. Nora is the daughter of an Irishman from Killarney. Her story accurately portrays the pride many Irish emigrants hold for not only their homeland, but their adopted country, as well: “In the summer of 1954, when [my father Jim] is 22, these two young women come to the show [in Killarney where he is playing accordion] and one is [my mother] Diane, from Utica. And basically, it’s a long story, but it’s love at first sight and it’s really romantic and beautiful.

Dr Jason King is the academic coordinator at The National Famine Museum and works with the National Heritage Trust

“In 1955, my mother and father were married in the Killarney cathedral on 30 June. It’s the first wedding in Ireland of a Yank to an Irishman, apparently, and so it is in all the newspapers at that time.

“In 1986 he actually becomes a naturalised [American] citizen. He chooses that year because there’s a lot of attention brought to a ceremony that they’re going to have - because it’s the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty - so there are a lot of articles written about immigrants and citizenship. But he decides he will become a citizen, so their friends have a little parade up Springgate Street, in front of the house.

“They have dad sit in a lawnchair in the dark, they have someone dressed as the Statue of Liberty, they have garbage can lids to make a lot of noise, they sing, they have sparklers - they have a parade just for my father. And I know that man is a man with no regrets: happy, proud to be here; to have the life he has. He has never looked back.

“In 2015 my husband Steve and I and my sister, Roisin, and my daughter take a trip to Killarney again with my parents. We stay in a rented house on New Street and we see all the sights again and they’re close enough to visit the cathedral where they were married for mass and walk in the national park.

“A cousin of mine, John Mooney, a couple of nights before we were leaving [on a Saturday] says, ‘I want to bring Jim up to a session.’ So we go up the street to the Arbutus Hotel and my father is 83 now - he has lost all the hearing in one ear and has a hearing aid in his other ear.

“My cousin seats him near the musicians; next to the accordion player - who is known to my cousin - and after about an hour, this accordion player - he passes his accordion to my dad and asks, ‘Would you give us a tune?’

“So dad takes it and he fumbles a little and then he gets his notes and he’s off playing two or three tunes. And it is a clear and beautiful sound and the people in that bar, on that Saturday night stop. They stop talking, they listen - there’s a hush. It’s really incredible to me, because I’ve always heard him play, but I don’t know that he’s very good or not. But apparently it’s beautiful.

Read more

Tales from the Parish: the famine orphans of Quebec

Tales from the Parish: the 12th Lancers of Dungarvan

When Jim Callery purchased Strokestown Park House in the late 1970s, aside from the physical estate, he also received all of the historic house records. The Co Roscommon founder of Westward motor group found among them many personal and painful accounts of tenants pleading with their landlord to help them and provide respite during a time when their crops were failing.

Jim was struck by these letters, which started from the year 1846. As it turns out, he had found what is now considered one of the largest collections of famine-related material in the world. This led to the establishment of the National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park House and Gardens in 1994.

National Famine Commemoration Day

The museum recently underwent an extensive re-vamp, with academic coordinator Dr Jason King promising visitors a more interactive experience for those coming to learn about the famine through these archival accounts and artefacts.

“Strokestown was one of the most devastated areas affected by the Great Famine in 1847, and emigrants from Strokestown sailed on some of the worst of the coffin ships,” he says in the National Famine Museum’s latest educational video entitled “The National Famine Museum, Strokestown Park”.

Great Famine Voices of New York State features stories from Irish emigrants in four Irish centres in New York State, along the Erie Canal.

The video was launched both in honour of National Famine Commemoration Day, which took place this past week (15 May) and to celebrate the reopening of the museum, which is set to happen in the coming weeks.

It showcases the museum’s new facilities, interactive displays and archival records, which offer insights into the parallel lives of the cottiers, tenants and landlords who experienced the Great Irish Famine.

Great Famine Voices

Emigration was a major response to the famine as it resulted in many Irish moving abroad; particularly to regions within North America. I recently spoke with Jason about some of the museum’s ongoing projects.

“We have our annual Great Famine Voices season of short films,” he says. “Its purpose is to gather stories from Irish emigrants and their descendants - to recall their stories of migration from Ireland to the United States, Canada and Great Britain (for the most part, during the periods of the Great Hunger, but afterwards as well) and our premiere video this season was [entitled] The Famine Irish in Chicago.”

This series not only documents why Irish emigrants came to America and shares their stories; it also explains and emphasises the significant work Irish immigrants accomplished in building the infrastructure and political landscape of the modern-day United States.

“[The Irish] played a big role in building the [physical] infrastructure, but they also played a very important role in the development of Chicago politics,” Jason explains. “The Famine generation in particular helped build the Democratic Party and played an instrumental role in shaping its policies.”

The series can be viewed on Youtube by searching or subscribing to Great Famine Voices. There will be eight films released this year – the releases began the first week of May and will continue until 19 June.

“As of now, we have released the ‘Famine Irish in Chicago’ and ‘Great Famine Voices New York State’ [videos],” Jason says. “The latter features stories from Irish emigrants in four Irish centres in New York State, along the Erie Canal.”

As is our wont with our Tales from the Parish series, we couldn’t publish this article without sharing one of the stories featured in the Great Famine Voices series. This story is told by Nora Keating of Utica, New York State and features in ‘Great Famine Voices New York State’. Nora is the daughter of an Irishman from Killarney. Her story accurately portrays the pride many Irish emigrants hold for not only their homeland, but their adopted country, as well: “In the summer of 1954, when [my father Jim] is 22, these two young women come to the show [in Killarney where he is playing accordion] and one is [my mother] Diane, from Utica. And basically, it’s a long story, but it’s love at first sight and it’s really romantic and beautiful.

Dr Jason King is the academic coordinator at The National Famine Museum and works with the National Heritage Trust

“In 1955, my mother and father were married in the Killarney cathedral on 30 June. It’s the first wedding in Ireland of a Yank to an Irishman, apparently, and so it is in all the newspapers at that time.

“In 1986 he actually becomes a naturalised [American] citizen. He chooses that year because there’s a lot of attention brought to a ceremony that they’re going to have - because it’s the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty - so there are a lot of articles written about immigrants and citizenship. But he decides he will become a citizen, so their friends have a little parade up Springgate Street, in front of the house.

“They have dad sit in a lawnchair in the dark, they have someone dressed as the Statue of Liberty, they have garbage can lids to make a lot of noise, they sing, they have sparklers - they have a parade just for my father. And I know that man is a man with no regrets: happy, proud to be here; to have the life he has. He has never looked back.

“In 2015 my husband Steve and I and my sister, Roisin, and my daughter take a trip to Killarney again with my parents. We stay in a rented house on New Street and we see all the sights again and they’re close enough to visit the cathedral where they were married for mass and walk in the national park.

“A cousin of mine, John Mooney, a couple of nights before we were leaving [on a Saturday] says, ‘I want to bring Jim up to a session.’ So we go up the street to the Arbutus Hotel and my father is 83 now - he has lost all the hearing in one ear and has a hearing aid in his other ear.

“My cousin seats him near the musicians; next to the accordion player - who is known to my cousin - and after about an hour, this accordion player - he passes his accordion to my dad and asks, ‘Would you give us a tune?’

“So dad takes it and he fumbles a little and then he gets his notes and he’s off playing two or three tunes. And it is a clear and beautiful sound and the people in that bar, on that Saturday night stop. They stop talking, they listen - there’s a hush. It’s really incredible to me, because I’ve always heard him play, but I don’t know that he’s very good or not. But apparently it’s beautiful.

Read more

Tales from the Parish: the famine orphans of Quebec

Tales from the Parish: the 12th Lancers of Dungarvan

SHARING OPTIONS